‘Place-based Learning for the Plate’ explores relationships with food and land

By Mackenzie Miller ’21

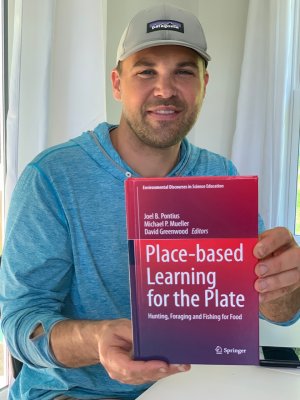

“How do we integrate places more intentionally into our lives and our lives more consciously into places,” is the question at the heart of Joel Pontius’ first book, “Place-based Learning for the Plate,” which explores 21st century stories of hunting, foraging and fishing for food.

The book was co-edited by Michael P. Mueller, David Greenwood and Pontius, assistant professor of sustainability and environmental education at Goshen College’s Merry Lea Environmental Learning Center. An idea born while Pontius was writing his dissertation in Wyoming five years ago, the book also speaks to a lifelong curiosity for the environment and engagement with gathering as a child.

“When I was nine, I received an incredible gift along the thunderstorm-flooded shoreline of a small reservoir in North Central Indiana,” Pontius writes in the book’s preface, a reference to catching crayfish for a family meal.

“Place-based Learning for the Plate” features chapters written by people from within the Goshen College community, including Abbie ’98 and Andrew Gascho Landis ’00, English and environmental studies alumni who contributed a co-written chapter titled, “Thanksgiving in Alabama: Deer Hunting Among Paradoxes in the Black Prairie.”

Jonathon Schramm, associate professor of sustainability and environmental education, contributed a chapter titled, “Gathering Sap,” about the process of making syrup from sugar maples in his Goshen neighborhood.

The Sustainability Leadership Semester at Goshen College is also featured in the book, along with chapters from North American Indigenous people, people of color and multiple scholars outside of the United States.

“I hope this book will lead diverse people into conversation, reflection and action regarding their own relationships with their places, food, self and more-than-human community,” Pontius said.

Pontius solely wrote two chapters of the book, in addition to his role as co-editor.

“As I rode my bike to my writing place, walked the land and ran on the trails at Merry Lea for breaks, ideas would emerge, connect and come into focus,” he said.

Pontius hopes the book will be useful in courses on food studies, place-based learning and human dimensions of wild land management, as he plans to reach out to college and university departments who are teaching in these areas. He also plans to connect with natural resource management agencies like the Indiana Department of Natural Resources and the National Fish and Wildlife Association.

“The pandemic prevents a physical book tour, which I wanted to do, but I’m looking forward to doing talks online and through other venues that don’t require travel,” he said.

Beyond themes of place and food, Pontius sees the book as connecting these ideas to issues of identity, activism, spirituality, food movements, conservation, traditional and elder knowledge, and the ethics related to eating the more-than-human world.

This “more-than-human world” is a term coined by human ecologist and philosopher David Abram, which Pontius uses in acknowledgement that “all creation is sentient in its own way,” he said.

“We can learn to experience the deeper spiritual interconnectedness of the earth by acknowledging with our language and our actions that there is a lot more going on here than the dominant, human-centered story,” Pontius said. “We are made completely from the earth, from the other-than-human.”

As writer and co-editor, Pontius says this learning continues to deepen, reveal, disrupt and reorient him toward a sense of wonder and gratitude for the sustenance that is all around us.

“The authors’ narratives reveal complex social and ecological relationships while readers sample the flavors of foraging in Portland, Oregon; feel some of what it’s like to grow up hunting and gathering as a person of Oglala Lakota and Shoshone-Bannock descent; track the immersive process of learning to communicate with rocky mountain elk; encounter a road-killed deer as a spontaneous source of local meat, and more,” he said.