President’s Speech: Reflections on Servant Leadership

Fall Opening Convocation message, delivered by Dr. Rebecca Stoltzfus, President of Goshen College, on Wednesday, Aug. 28, 2019, in the Goshen College Church-Chapel (as prepared for delivery)

Related:

» See photos from the opening convocation and applause tunnel

Good morning! Welcome to the 125th anniversary year of this institution. There’s a special word for this anniversary, which is very fun to say: quasquicentennial.

Goshen College was brought into being by ordinary people who saw potential and had the courage to develop that potential. By extraordinary leaders who were motivated by their own joy in the work, and also to create something for their community, as it was then and for the generations to come.

One of GC’s early students was Milo March. In 1913, Milo completed his first two years at Goshen College, went on to Princeton University, and then to Oxford on a Rhodes Scholarship. He later stated that it was at Goshen where “he really learned how to study.”

Each year, we focus on one of our five core values, and this year we focus on servant leadership. Leadership is a daunting word, and there are shelves of books and theories written about it. I’m going to steer clear of books and theories, and speak to you primarily from my own experience.

So here’s the outline:

- I’m going to lay a foundation, and ask you a big question.

- Then we’ll talk about three concentric circles,

- three mysterious symbols,

- and end back at the foundation.

Let’s begin with the foundation. This will be familiar to some of you, if you were here for our diversity, equity and inclusion convocation last January. Remember the 40-pound foundation stone that Jose Chiquito helped me lay in that convocation?

What is the foundation of our community?

Student in crowd: “The inherent goodness and dignity of each one of us.”

Yes! The inherent goodness and dignity of each one of us.

This foundation — that we are created in the image of God — makes every one of us deeply beloved and unspeakably precious.

Now, I don’t mean to gloss over the fact that people — including each of us — can also be annoying, infuriating, selfish, mean-spirited, and exhausting. By now, we’ve all experienced that. But it does not take away the foundational truth that we carry within us the light of God — each one of us, deeply beloved and unspeakably precious.

Servant leadership arises from the inherent goodness and dignity of ourselves and the people around us.

There is no single definition of leadership, but here is a good one.

“A leader is anyone who takes responsibility for finding the potential in people and processes, and who has the courage to develop that potential.” — Brené Brown, 2018

Now here is the big question: What is the potential that you want to develop?

Your answer might arise from something you love to do. It might arise from a longing for things to be different, a holy dissatisfaction with the way things are. Or, in the more vivid words of teacher, author and activist Parker Palmer, because you see the tragic gap between the way things are, and the way that things could be.

What is the potential that you want to help bring about?

In our culture, there are some false perceptions around what sorts of people can be leaders. I want to name those so they don’t get in our way.

The first is that you have to be really smart to be a leader. This is not true, at least not in how we normally define being smart, which is in terms of grades and IQ. Research shows that people who have demonstrated outstanding leadership, either formally or informally, are not as a rule exceptionally smart. Good leadership arises from a complex combination of attributes, and those depend a lot on the context and the issues at hand. Good leaders figure out the kind of smarts they need around the table, and they recruit that. You don’t have to be the smartest one in the room to lead.

We make other assumptions about good leaders based on social biases. For example, we tend to confer leadership to people who are highly social and confident talkers, to people who have cultural status, such as being male or white or wealthy, to people who are tall, and to people who are “normally abled.” These assumptions are so embedded in our culture that it is probably impossible for us to avoid holding them at least to some degree. It is important to be aware of these biases, because they do not determine leadership ability. I actively watch myself on these biases because it is so easy for them to creep in.

Also note that leadership does not require a title or formal position. Titles and positions are not irrelevant, but there is so much space for leadership outside of that. Leadership emerges when people take responsibility and decide to lead in large or small ways. And as you decide to lead, you might navigate your way into a formal position, or you might not. Dr. Martin Luther King and Mahatma Gandhi changed the course of entire nations without a formal position or title.

The truth is that great leaders can come from anywhere and are many sorts of people. People like us. If we do not understand that, we all lose out from a whole lot of lost potential. And we cannot afford that!

Look around you. “We really are the ones we have been waiting for!”

About 10 years ago, I was at a crossroads in my career. I had achieved many things professionally, and enjoyed a productive network of colleagues and opportunities in global health at a great university. But I was ready to develop some new potentials—in myself and in the world around me.

The potential I increasingly felt called to develop was college education. I wanted to shift the focus of my efforts from research to teaching, and in particular, to teaching undergraduates in ways that were relevant, inspirational and eye-opening. I sensed that the particularly challenging discipline of being an excellent teacher would help me become who I wanted to be, and it would allow me to have a greater impact on the well-being of the world that I care so passionately about. And that eventually led me back to Goshen College, because I believe in the distinctive excellence of the education we provide here.

I want you to think about three concentric circles. You might think of these as circles of potential.

This inner circle is yourself. You are here at Goshen College to develop the potential in yourself. This process never ends. Let me tell you, I’m 57, and I am continually working to find and develop potential in one deeply beloved person: me. The good news is that throughout life, you will find more and more potential in yourself.

One of the most powerful ways that you find and develop the potential in yourself is by engaging the second circle: your community. This is the circle that most of us focus on when we think about leadership. What is it that we want to change in our community, outside of ourselves? In my experience, when you begin to develop the potential in one circle, you develop the potential in the other circle. And that’s very good.

The third circle is what the Haudenosaunee people call the seven generations. The tribes of the Iroquois teach that each of us alive in this time are being shaped by the seven generations who came before us, and we will affect the seven generations who come after us.

Here is how G. Peter Jemison, a Faithkeeper of the Seneca Nation, puts it:

“You start to think in terms of the people who come after [you]. Those faces that are coming from beneath the earth that are yet unborn, is the way we refer to that. They are going to need the same things that we have found here, they would like the earth to be as it is now, or a little better.”

We are the seventh generation of the founders of Goshen College. They made this place better than it would have been without this college. Many people through many small and large acts of generosity and kindness over the past seven generations of Goshen College have given us the opportunity to learn together this year. What will we provide for “those faces coming from beneath the earth that are yet unborn?”

Let me ask you again:

- What is the potential that you want to help bring about?

- For the seven generations to come?

- For your present community?

- What potential do you want to develop in yourself?

Two weeks ago, I asked the faculty what potential they want to develop in their work this year. Here are just a few of their answers. They want to develop:

- Students and colleagues who feel valued and joyful

- Students’ belief in their ability to succeed

- Student and faculty research

- Cross-disciplinary work between sciences and humanities

- Purple Pride

- Actions to reverse climate change

- Students who recognize their own potential as leaders

- A sense of belonging for everyone.

And for me personally? Here is the potential that I want to bring about:

That Goshen College will be a place of joy, growth and purpose, preparing students to thrive in life, leadership and service.

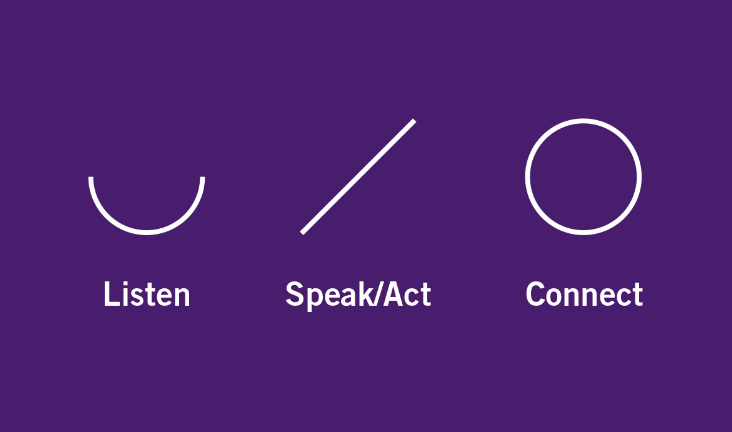

I want to share with you one more insight from my own journey as a leader. These are the mysterious symbols I promised you. I think of these as the three essential postures of my leadership. I reflect on them regularly and I draw them repeatedly in my journal to remind myself of them.

The first is an open bowl, which stands for listening. Good leaders listen to stories, to data, to the still small voice inside us, to the people whose lives will be affected by our decisions. This means knowing when to keep silent and give others space to talk.

Here is powerful little tool to help you increase your awareness of this. It is the acronym WAIT. It stands for Why Am I Talking?

It means becoming aware of your talking habits. Learning not to interrupt. Learning the art of asking inviting questions. Here’s my favorite: “Tell me more about that.”

The second is a slash, which stands for clear speech and decision-making. Speak up! Act! Cut through the fog.

The question “Why Am I Talking?” does not mean that you should never talk! Leaders need to speak and decide. But it helps you be aware of your speech. Good leaders speak with authenticity and clarity and timeliness.

The third is a circle, which stands for connecting. Good leaders create circles of connection and relationship. The kind word, the note, the small gift, the simple questions: Are you okay after that discussion? How are you doing? Practice the common courtesies: “Thank you,” and “I’m sorry.”

These are each simple things: Listening, speaking, connecting. The challenge for me and for you is to be aware of ourselves in action as leaders, and to use all three of these postures regularly and in balance.

Think about a setting in which you lead or interact. It might be a team or a formal meeting setting, or it might be your friend group. How are you balancing listening, speaking and connecting? Which of these do you need to do more of? Learn to watch yourself in action.

I want to conclude with a return to our foundation. Let us be aware that leadership can be for the common good, or it can bring about suffering and destruction. What do we mean by the common good? We mean something larger than ourselves.

Not all leadership is good leadership. This why our core value is servant leadership. Servant leadership is moral leadership that finds the potential for GOOD in people and processes, and that has the courage, creativity and compassion to develop that potential in ways that are good—for you, for your community, and for the seven generations to come.

And because we are rooted in the way of Jesus, we embrace leadership that is inclusive, loving and nonviolent. Leadership that is grounded in the inherent goodness and dignity of each one of us. Leadership that does our utmost not to harm others through our speech or through our actions, and yet has the courage to speak and act.

The good news is that nonviolence is not only moral, it is effective. Erica Chenoweth is a Harvard professor who researches the effectiveness of nonviolence. Her research shows that nonviolent resistance to injustice is “nearly twice as likely to achieve full or partial success as their violent counterparts. Nonviolent campaigns have greater participation, loyalty, resilience, innovation and civic impact than violent ones.”

Let our leadership be grounded in goodness and creative non-violence no matter the scale.

I want to close by thanking you: the students, staff and faculty leaders who will develop the potential of Goshen College this year, who will make our community stronger and more excellent and more joyful, and are working to leave this place as it is now or a little better, for those who will come after us. Thank you for your leadership, formal or informal, in social movements large or small. Even seemingly small acts of leadership can have a large collective impact.

I’ve been asking you what is the potential that you want to develop, beginning with yourself. Send me an email…I’d love to hear from you. And I’ll tell you mine. At the level of my inner circle, myself, I want to develop greater courage.

The poet and author Maya Angelou said that:

“Courage is the most important of all the virtues, because without courage you can’t practice any other virtue consistently. . . . One isn’t necessarily born with courage, but one is born with potential. You develop courage by doing small things — just as you wouldn’t want to pick up a 100-pound weight without preparing yourself.”

So let’s work it out. There’s going to be some sore muscles. Servant leadership is something that we practice. So let’s get started.

So let this quasquicentennial year of Goshen College begin! I wish you all abundant joy, growth and purpose this year.