Quasquicentennial Touchstones

This story originally appeared in the Fall/Winter 2019 issue of The Bulletin

By Susan Fisher Miller ’79 and Joe Springer ’80

Authors’ Note: These “touchstones,” events and themes selected from each quarter-century of Goshen College’s 125-year history, represent both specific moments in time and larger symbols of institutional identity. We invite you to consider how the following touchstones — five from among many — resonate with each other and across time, with the unfolding mission of Goshen College. Interested in more of the story?

1894-1919 | Coming to Goshen

1. Wilbur Stonex, one of the primary leaders of Goshen’s civic efforts to recruit Goshen College

2. H. Frank Reist 1904, future GC President

3. J.S. Hartzler, GC business manager and Bible instructor

4. John E. Hartzler 1910, future GC President

5. Anthony Deahl, Goshen attorney and a leader in the civic recruitment effort

Goshen College’s June 1903 groundbreaking ceremony rooted the institution in a specific tract of farmland (a stubbly wheat field cleared just in time for the ceremony), but also in the broader civic landscape of Goshen, Indiana, whose enterprising business leaders raised prodigious funds to win the Mennonite Church-directed college for their city. Businessman Wilbur L. Stonex had argued that a college would deliver more benefits and cultural riches to the community than a factory. Now the higher educational beacon of its proud sponsoring community, Goshen College in its early decades would enjoy easy and regular interactions with Goshen town citizens and institutions, including in shared worship spaces and with local non-Mennonite young people who soon enrolled as students. Photographed looking north toward downtown from the site of the future Administration Building entryway, the portrait of Goshen College’s 1903 groundbreaking crowd — the grinning Elkhart Institute delegation squeezed in alongside Goshen civic leaders and their families in a happy sea of plain coats, bonnets, bow ties and elaborate picture hats — captures a giddy moment of cooperative promise.

After breaking ground for the future campus, many in the crowd rode chartered trolley cars back to Elkhart to mark a final graduation in that city. Elkhart Institute had begun modestly in rented quarters in August 1894. Soon supporting stockholders funded construction of what had seemed a substantial building. But on that June evening, the still-new building was already too small to handle the commencement crowd. The Institute’s Class of 1903 would enshrine its class motto, Vorwärts und aufwärts (Onward and upward), in the façade of the soon-to-rise Administration Building. A reminder of the past, this stone continues to point us to the future.

1. Orie O. Miller 1915, future founder of Mennonite Central Committee

2. Ernest E. Miller 1917, future president of GC

3. Walter E. Yoder ’33, music instructor

4. Paul E. Whitmer 1905, dean

5. Alvin J. Miller 1911, history instructor, director of Goshen Choral Society

6. John S. Winter, education professor

1920-1944 | Old Goshen, New Goshen

An August 1914 performance by Goshen College students, faculty and local citizens on the campus lawn of Handel’s oratorio “Saul” provides a window on the college’s first two decades in Goshen, an era that, after college-church tensions resulted in the closing of the college for one year in 1923-24, came to be called “Old Goshen” (p. 22). Viewed as Edenic by some and dangerously liberal by others, Old Goshen was the laboratory in which the present Goshen College first sparked to life.

The choice of a sacred oratorio on a biblical theme was consistent with Goshen College’s religious priorities. At the same time, the production — replete with costumes — was characteristic of Old Goshen’s high cultural ambitions. Music performance, oratory and athletics activities rounded out a Goshen education, pushing the boundaries of traditional Mennonite prohibitions. Critics feared Goshen was grooming students to forsake traditional nonconformity and join mainstream American liberality. External criticism exacerbated the precarious financial footing of the fledgling institution, resulting in the board’s decision to close the college at the end of the 1922-23 academic year.

In the year following, committed leaders labored so that a “New Goshen” could open in the fall of 1924. New President S.C. Yoder and Dean Noah Oyer applied conciliatory skills and wisdom to reopen a more viable endeavor. Some of the ablest products of the oft-maligned Old Goshen education formed the core of a vigorous new faculty. Conflicts and griefs inherent in the original venture — promoting education in a Mennonite context — did not disappear completely.

Still, the renewed effort found more secure footing that allowed Goshen College to rise again, survive the Depression and achieve full accreditation before its second quarter century would end.

1945-1969 | Engaging the World

The tumult of World War II opened Goshen College to new encounters with the world. Growing numbers of students and faculty could rely on globes to track future or past periods of service or education. Some of Elkhart Institute’s earliest students had heeded the exotic call to India. The aftermath of World War I had sent students to strife-torn areas in Europe, the Near East and Russia. In the 1940s, many GC students still hailed from rural communities. Alternative military service requirements for “work of national importance” exposed many in GC’s applicant pools to smokejumping, reforestation projects and work in state mental hospitals. Participation away from home in such work also increased greatly the number of young Mennonites interested in pursuing higher education. At Goshen, faculty mentors and student peers were actively engaged in post-war relief in Europe and Asia. Soon they ventured on to teaching and development work in Africa, and beyond. A steady influx of international students enhanced the on-campus impact of experiences North Americans brought home from abroad. When GC sought reaccreditation in 1965, external observers noted that over half of the teaching faculty had some sort of international experience. In looking to its future, the college decided to build on this evolving strength, launching the Study-Service Trimester (SST) in 1968.

1970-1994 | Potters and Poets

“Goshen begins with the assumption that what is odd, exceptional and different may nevertheless be worthwhile, if not revelatory.” One could apply departing President J. Lawrence Burkholder’s ’39 1984 characterization of campus culture to most of GC history.

It seems particularly apt in describing the way GC’s academic boundaries expanded during our fourth quarter century. The early 1970s at Goshen College unleashed a flourishing of the imaginative and unconventional — mirroring American trends, but distinctly rooted in campus culture. The teachers, nurses, doctors we continued to prepare carried SST-shaped life experiences with them. But they also studied in an on-campus environment sprinkled with the “odd, exceptional and different.”

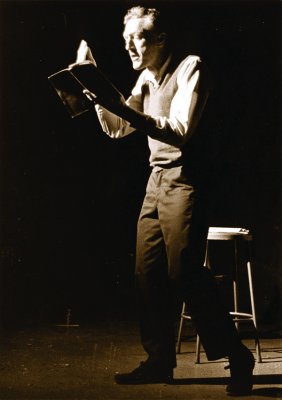

The poet Nicholas Lindsay joined the English Department faculty in 1969 with a voice of thunder and a kinetic teaching style unfamiliar in Goshen’s classrooms. Lindsay tapped into the elemental, the archetypal, the Divine. Imbued with intriguing outsider credentials, he became an influential apostle of Goshen creative writing, founding Pinchpenny Press (which still continues strong) and inspiring students to become poets.

Lindsay was not alone in thinking outside the pedagogical box. For decades, professor of music Mary Oyer ’45 had taught a peerless course in the classical fine arts. A sabbatical in Kenya broadened Oyer’s gaze, and that of her students, to encompass thumb pianos, drums, indeed myriad artistic and musical forms of world cultures. Just as Lindsay led students toward the non-conformist profession of poetry, professor of art Marvin Bartel ignited a student passion for making pottery, resulting in an uncommon number of life vocations in ceramics. Perhaps the most novel curricular experiment of the period was a course called “Creative Expression” — inventive in concept but a difficult sell to students — who loved freedom of choice but objected to mandated creativity.

1995-2019 | Doors of Welcome

What differences exist between GC at age 100 and 125? A 1994 alumnus might notice many. Only 10 percent of 1994 faculty still teach here. In 1994, GC had not yet had a female president, nor offered a master’s degree. The Music Center, the Connector, Romero Student Apartments? — not yet built. Today, with the addition of an underpass, trains no longer provide an excuse for being late to class.

Campus sidewalks of 1994 carried more people, but the variety of people traversing today’s sidewalks has increased significantly. What has moved us from a campus with a white student population of around 85 percent in 1994 to today’s 56 percent? Especially notable is the rise in Hispanic student population to over 25 percent. In the late 1960s, GC began repeated, though not always successful, efforts to increase racial diversity. In 2001, Lilly Endowment invited GC to consider how it might use a “transformational” gift. Early ideas imagined “bridges” to the rapidly-growing local Hispanic population. In 2006, Lilly supported creation of the Center for Intercultural Teaching and Learning. Running through 2012, that grant sought to make GC education accessible to Latino and other diverse groups, increase all GC students’ intercultural learning and study Northern Indiana’s changing demographics and their implications for higher education.

Through changes in core curriculum, support for students and families, decisions about resources and organizational change, GC seeks to move “beyond hospitality” — and is enriched by the changing faces on its sidewalks. Touchstones of 125 years — engaging Indiana and the world, fusing faith and the liberal arts, finding revelation in the unconventional — are echoed, and enlarged, in the words of our recently-revised vision statement: to prepare “students to thrive in life, leadership and service. Rooted in the way of Jesus, we will seek inclusive community and transformative justice in all that we do.”

Susan Fisher Miller ’79 was the author of the college’s centennial history book, Culture for Service, and is a member of the GC Board of Directors.

Joe Springer ’80 is curator of the Mennonite Historical Library on campus. Both were born into Goshen College faculty families at the midpoint of the college’s 125-year history, and have been involved observers of GC throughout their lives.