Gangs and Jesus

Today we had extensive and moving sessions on Guatemalan gangs and on Jesus and spiritual imagination, and then we finished the day with group processing of our learnings and a later-evening, balloon-festooned 18th birthday party for Erick.

In a recent journal entry, Maura said (quoted with her permission) in relation to how being an SSTT student is different from being a tourist: “The SSTT program is designed around the students getting to understand the various aspects of the country’s culture better – which can mean going to places that aren’t exclusively fun in order to fully experience and see all aspects of the country to better understand it. SSTTers are students learning how to experience a country, how to think critically about situations, how to understand a culture, and how to use that to better understand yourself and God. Before I came to Guatemala, I didn’t know what to expect. People had told me stories, but none of them were able to give me a clear picture of what Guatemala is like. Now I have a clearer idea of what this culture is like. These are people. People who have struggled. People who have not given up. Tenacious, strong, kind people. I had heard some about the issues Guatemala had – sexism, poverty, government corruption – but those were just words to me until I was able to see what that meant. Words are just words to me until I experience them. Guatemala is filled with God. God is where struggles are. God is wherever there is poverty, inequality, corruption. And God is hope. He is in the kindness. He is in the tenacity.”

In that vein, this morning’s sessions were powerful, beginning with a lecture on Guatemalan young people and gangs by Robert Brenneman, a professor of sociology at St. Michael’s College in Colchester, Vermont, and the author of Homies and Hermanos: God and Gangs in Central America (Oxford, 2011). Brenneman is finishing up a year-long sabbatical in Guatemala City while his spouse is interim country director for Mennonite Central Committee.

Brenneman first came to Guatemala as a college student, and then returned with Mennonite Central Committee just after Guatemala’s civil war ended (1996). The homicide rate initially dropped, but then leapt back up by the late 1990s, partly because so many former military personnel lost their positions. From the bloated military, about two-thirds of soldiers were downsized and a quarter of the officers were put out of work, but they were not easily integrated back into the Guatemalan work force, and some ended up in crime (bank robbery, extortion), as private security guards or in other spheres that used their previous military skills in non-military contexts. At the same time, local street gangs began to rise and then form what were essentially franchises of transnational gangs, with whom they affiliated so they could get information about how to get things done and purchase weapons and drugs.

Brenneman argued that government strong-armed, tough-on-crime approaches to gangs do not work. He said that in addition to food and shelter, every human being needs to belong and be respected. While most people find these needs met in families, the workforce, church youth groups, school, or elsewhere, those who join gangs don’t have access to these avenues for respect and belonging. In his dissertation research with ex-gang members in Central America, Brenneman discovered how difficult it was for gang members to leave the gangs, partly because they were threatened by the gang for being deserters, and partly because they had burned their bridges with family and friends.

In hundreds of cases, however, gang members successfully left those gangs with the support of Evangelical and Pentecostal churches, who became a place of refuge for people who wanted to get out. Gangs believe, said Brenneman, that you “don’t mess with Curly (God),” so being an authentic convert to Christian faith is considered one legitimate way to depart from gang life. And conservative Protestant churches tend to believe deeply in the power of transformation: that anyone can be changed by the love of God. “Gang members found in those communities people who were willing to take a risk on the possibility of human change.” Brenneman said to the SSTTers. “I’m glad that some of you are taking steps to be co-architects of these communities of faith, churches that believe in human transformation.”

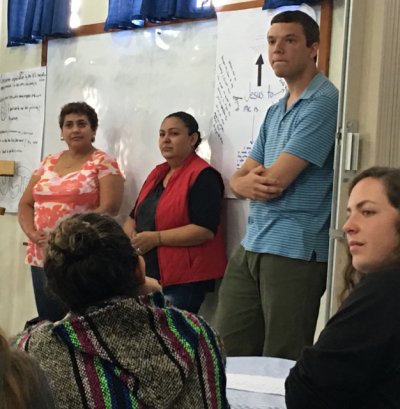

Immediately after Brenneman’s sociological lecture, we were able to meet Angela, a former gang member and now a member of a Mennonite Church in Guatemala City’s Zone 6. She was accompanied by the church’s pastor, Janet Palacios. Pastor Palacios said, “The church wants to show through their actions how to live a different kind of life,” in the midst of a zone that is filled with crime and drugs and prostitution.

Angela talked about being recruited by a gang when she was 13 years old, after experiencing abuse/discrimination from her father. “I felt like no one loved me, I was outside of society, and I felt worthless,” she said. “What has changed me is the blood of Christ.” She talked about the difficult of getting jobs with drug-trafficking and selling weapons on her record. Angela spoke with deep appreciation for the love of Pastor Palacios, who believed Angela could change and supported her in the midst of discrimination and hatred from others. “The church has a calling to be loving to those who haven’t had that love in their lives,” said Pastor Palacios. This session had an incredible impact on students, who were moved by Angela’s life story.

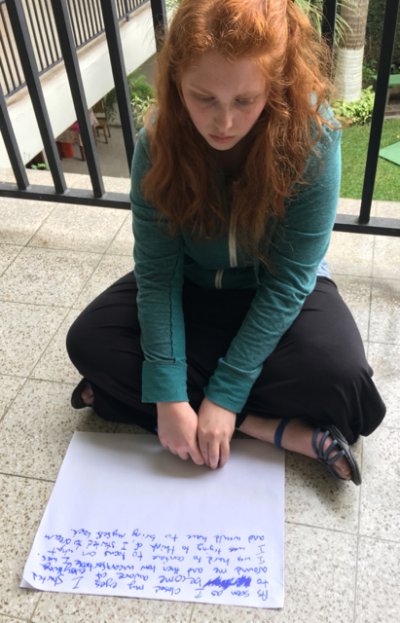

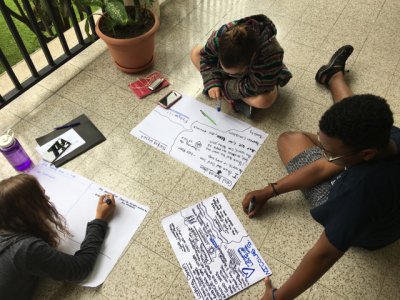

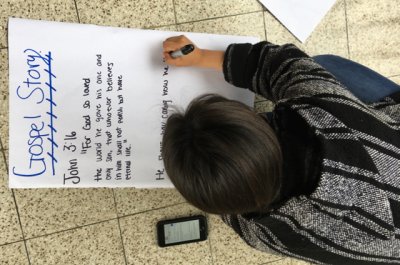

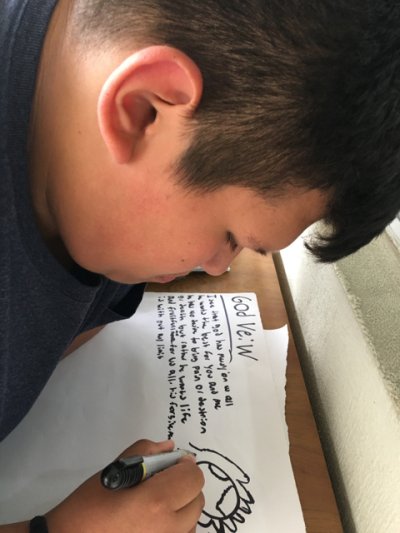

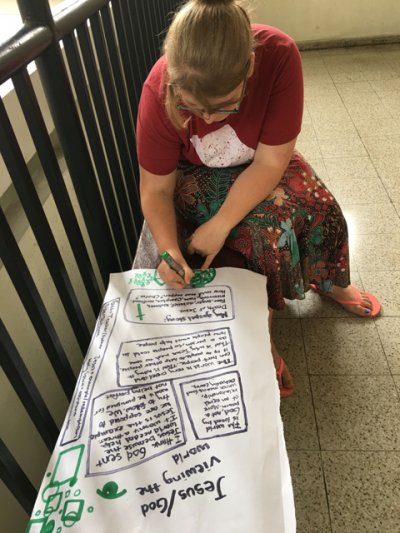

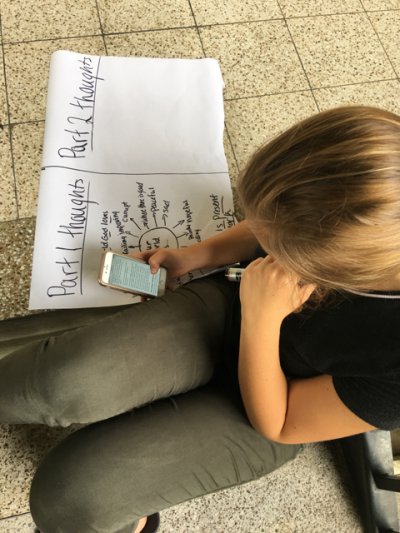

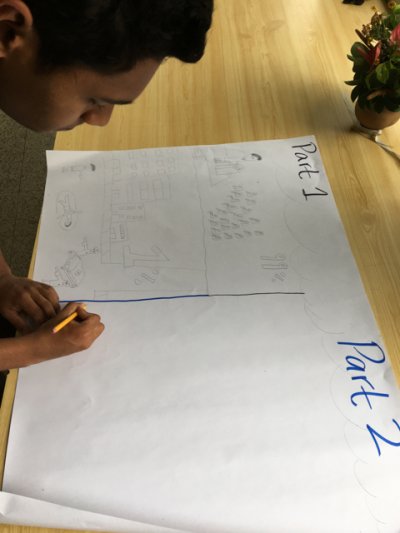

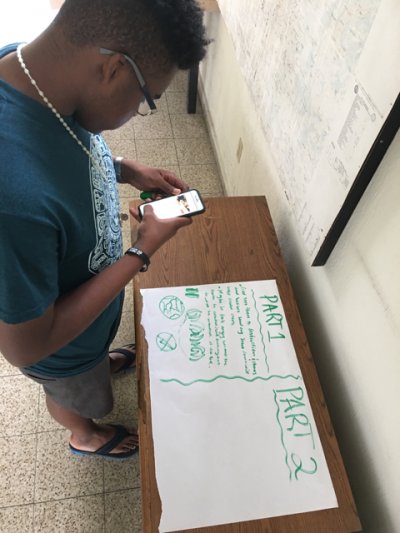

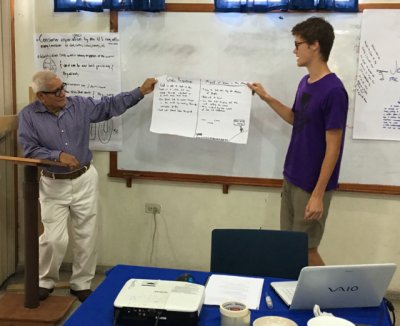

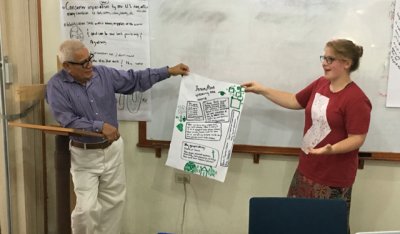

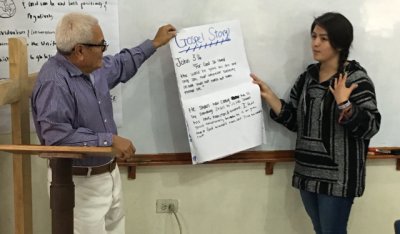

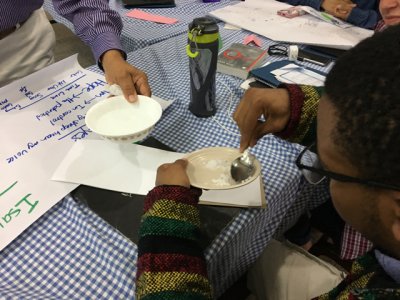

This afternoon we talked extensively with Professor Flores about Jesus and Vocation, thinking about spiritual imagination. Students did solo work, preparing posters addressing how God may see us from God’s perspective, and then putting themselves in a Gospel story or passage. They also thought about what it means to be salt and light in the world.

In a recent journal, Anna wrote (quoted with her permission): “During our class, Jesus and Vocation in the Contemporary Context, I have grown spiritually and mentally. I’ve also developed a new perspective of the Guatemalan people based on the learning and stories that have been told in our class during the past week. In this context, as we’ve studied what Jesus’ life would have been like and also the 10 trends that are dominant in our society today, my views and perspectives have changed. We talked about Jesus’ peaceful approach to violence, and we applied that to the context of our society today (and its effectiveness). Throughout my life, I’ve heard about how Jesus gave his life for us, for our sins. But, what interested me in one of our lessons, was the idea of the cross, paying the cost. Two concepts also went with this, the two invitations to follow. One was that we should follow Jesus (with no risks) only to learn. The second way would be to follow Jesus all the way (with all the costs). Along with this, and the resurrection, Jesus is a model. These ideas challenge my faith, and have made me think differently about this idea.”

We met at 7 p.m. for group processing time, and then moved from that reflection period to a rousing birthday party for Erick, the second SSTT Scholar to experience their birthday in Guatemala.