Education, Racism, Gangs and the Fullness of Humanity

We remained on the SEMILLA campus all day today, which was a good break from travel and yesterday’s flurry of activity. We also were fortunate to have input from multiple different people who introduced us to Guatemalan social realities and also our program on “Youth and the Fullness of Humanity.”

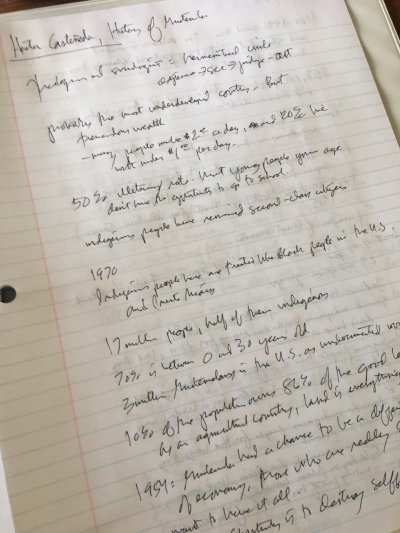

The day began with a dynamic lecture by pastor, theologian and sociologist Hector Casteneda, who spoke briefly about Guatemalan history, including the brief period of democratic rule in Guatemala (the Ten Years of Spring), followed by a coup largely engineered by the U.S., mostly designed to protect the interests of the United Fruit Company (UFCO) and other major businesses, whose land was being partially nationalized. At the time, the Eisenhower Administration’s Secretary of State was John Foster Dulles, who was an UFCO shareholder and partner in the legal firm representing the United Fruit Company; Dulles’ brother Allen was the director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and also a major UFCO shareholder. Together the brothers and other U.S. administration officials drummed up concern about the “communist threat” from the beloved and democratically elected Guatemalan government, resulting in a coup that then led to 36 years of devastating civil war (1960 to 1996) for the country. “Guatemala had a chance to have a different kind of economy,” said Casteneda, “but those who are really selfish want to have it all.” The pastor/professor added: “The mission of Christianity is to destroy selfishness: that’s the original sin.”

Casteneda also spoke about the half of the Guatemalan population that is one of 23 different indigenous groups, and noted the racism against these groups that is prevalent in Guatemala. Such racism, he said, is similar to the racism against African-American people that he witnessed as a student in the U.S. in the 1970s. The other half of the population is sometimes referred to as “Ladino,” which means a mixture of Spanish, Indian and African ancestry. Ladinos have been in power in Guatemala since the 1870s.

We also heard a moving testimony from Angelita, a former gang member who now is part of a Guatemalan Mennonite congregation. Angelita’s pastor Yanett, who is president of the Evangelical Mennonite Church in Guatemala, also participated in the session. Angelita came from an abusive home, and decided to join a neighborhood gang at the age of 13. “Most of the kids I hung out with as a teenager are dead now,” she said. She became pregnant at age 17 and again shortly thereafter, but lost two babies because she was taking drugs at the time. Eventually, she decided she wanted to leave the gang, but leaving is difficult; the Mennonite congregation helped her find her way out and supported her and her family. The Mennonite congregation she is a part of consists primarily of women who are quite active with social programs in their neighborhood and community. Partly because many local gang members were — as children — recipients of food that was given by the church’s childhood nutrition program and recipients of other social service programs, the church has avoided any gang violence.

Following Angelita’s testimony, we heard from sociologist Robert Brenneman. Dr. Brenneman spoke from his Vermont office, but we were able to Skype him into our classroom. Robert wrote his dissertation and book Homies and Hermanos: God and Gangs in Central America after interviewing 63 former gang members in Guatemala and elsewhere in Central America. Twenty years ago Brenneman had come to CASAS as a college student to study, and he was inspired by the questions he encountered during his time here.

Brenneman said that in addition to needs for food, water and shelter, we also have social needs, in particular the need to belong and the need to feel respected. Most of us get that sense of belonging and respect from our families, athletic teams, school accomplishments, church youth groups, peers, friends and other social settings. But what about kids whose parents aren’t on the scene, or who are unable to go to school, or who feel like outsiders in their neighborhoods? Those who experience rejection from these other social institutions sometimes seek for belonging and respect in gangs.

In Central America, then, one of the only ways to leave a gang alive are to join a church, which typically gangs won’t harm, and to live an authentically Christian life. Sociologically, said Brenneman, churches often function like gangs, in terms of offering respect and belonging, providing activities that keep members busy throughout the weekend, requiring specific codes of conduct, and practicing rituals (e.g., baptism vs. gang initiation) that offer the initiate a new name and new personhood. Moreover, in Latin America, Pentecostal and Evangelical churches are among the few institutions that believe a person can be fully transformed into a new being, allowing for exiting the gang with integrity and support.

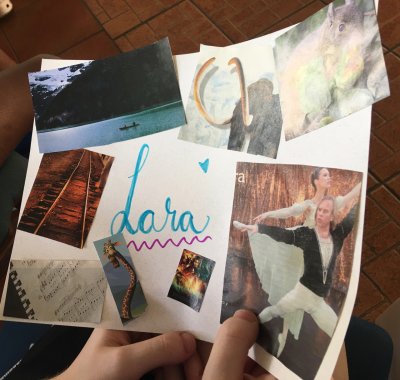

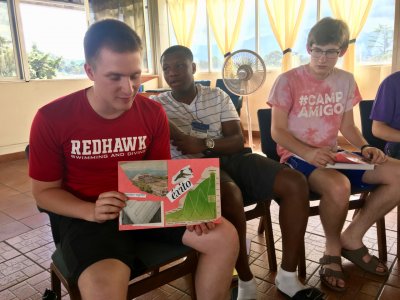

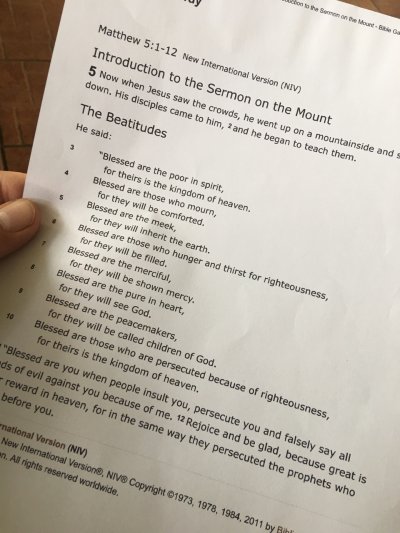

In the afternoon, we heard from CASAS Director Andrea Moya and Mario Chavez, who are leading our daily sessions on “Youth and the Fullness of Humanity.” The group reflected briefly on the Beatitudes, one of the primary texts being used for those sessions, and created collages that represented different parts of their identity. We also met Erin Helmuth Smeltzer, a 2013 Goshen grad who knew both program assistant Brook and Andrea while at GC, and who spoke briefly about her work with Common Hope in Antigua, Guatemala. Common Hope works with the whole family to support young people to finish high school; at this point, only 18 percent of Guatemala’s population finishes high school, which means most of the population is not able to enter the professional sector.

Students are now journaling about today’s extensive input that introduced them to a number of Guatemala’s social realities, helping them to think theologically about these realities and to consider appropriate responses for themselves and the church. This evening after dinner we’ll view together the film “Finding Oscar,” a feature-length documentary about the search for justice in the Dos Erres massacre in Guatemala in 1982. We’ll follow the heavy film with some processing before heading off to bed. These have been intense days filled with rich input and experiences.

Kudos to parents, siblings, extended members and friends for raising and supporting these amazingly thoughtful young people who are finding their way in faith and vocation. We feel fortunate to be shepherding them along in this Guatemalan context. And thanks to our Guatemalan hosts for their graciousness in facilitating our learning.