Peruvian Portraits

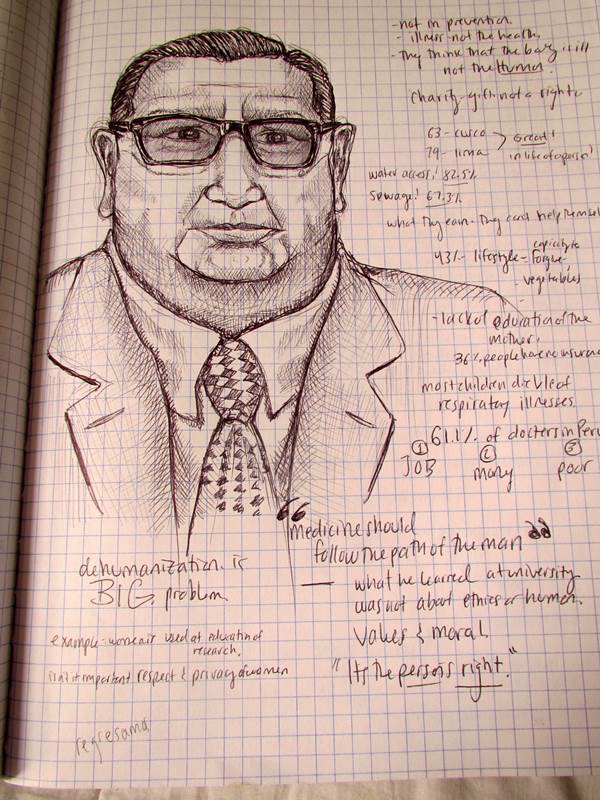

Anna’s journal is filled with the expected (written notes from lectures and field trips) but also the unexpected (sketches of many of our guest speakers). She captured Dr. Roberto Tarazona, a director of the Peruvian affiliate of Caritas, the Catholic relief, development and social services agency. During his presentation Dr. Tarazona said that about 30 percent of Peruvians live in poverty or extreme poverty. “Poverty in Peru wears a campesino face,” he said.

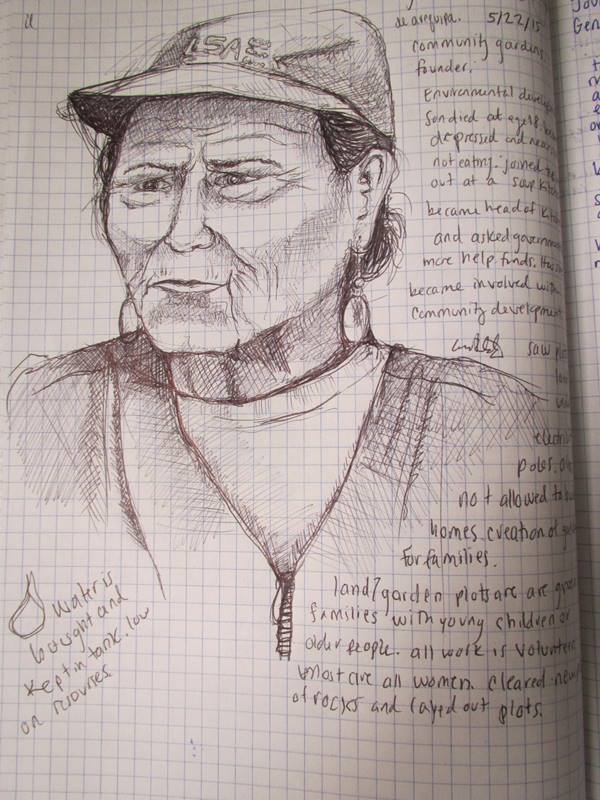

Another sketch is of Maria Doraliza Chavez, the president of a neighborhood garden in San Juan de Miraflores. She is working the tutelage of Señora Gregoria Flores, who oversees a series of community gardens in the Southern Cone of Lima. Señora Gregoria and her crew of volunteer gardeners start out on a hillside of pure sand, mixed with stones, topped with decomposing garbage. Where others see entrenched poverty, Gregoria sees green. In time, her vision will win out.

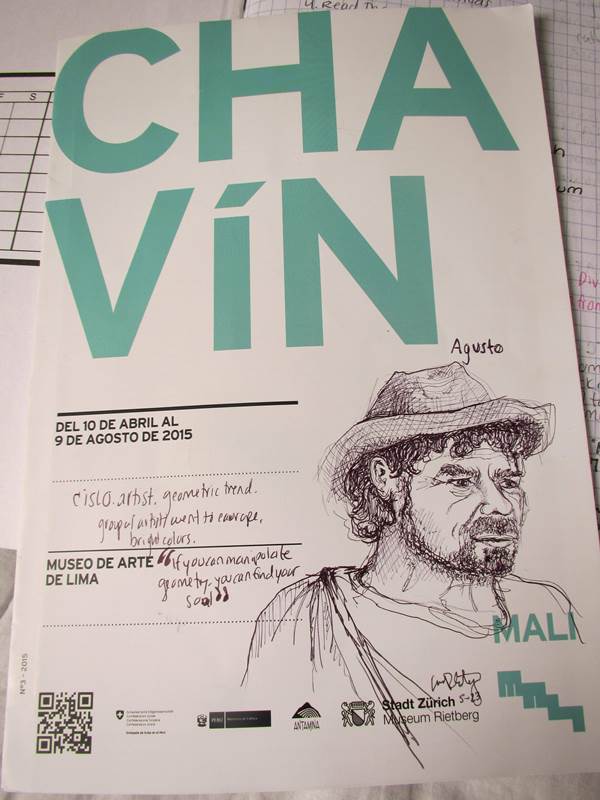

Augusto Del Valle met us at the Museo de Arte de Lima one Saturday morning. He served as the curator for a current exhibit on geometric art in Peru (1947-1958). It was great to have the curator explain how the collection came together. In an interesting side note, two of the pieces on display, “Geométrical” and “Estudio 60,” were created by José Bracamonte Vera, the father of one of our Spanish professors, Ana.

Here is Anna’s journal entry:

There is something very magical and intimate when I draw the “face” of someone. When doing so, there is so much concentration on the smallest details, such as their wrinkles when they smile; their creases around the nose; the shadows of their foreheads; and the texture of their hair. As I said, it’s intimate!

The most difficult yet important part is drawing their eyes. I never want to just draw an eye. It has to be their eye. I think to myself: What have they witnessed? What are their joys? Or what sadnesses or trials in life have they seen?

It may seem a little necessarily deep, but in order to really capture the individual, I have to think of how the person is fully human and is living. The best time to draw someone, I have found, is during their presentations to the class. It helps me to concentrate, relax and be fully in the moment. Since I am also a visual learner, having a drawing of the presenter in my notes helps their story come to life.

All I need is my pen (a specific pen) and paper. Pen is the most fun and challenging to draw with because every line is permanent. It really forces me to be extra observant and thoughtful.

So far I’ve completed nine drawings. One of them was given as a gift to my host mother, and one as a gift to the presenter herself (poet Celia Luz Flores). One was created on the museum brochure for the Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI); one was created on the hill of the gardens in Cono Sur; and another torn out and thrown away because I was very displeased with its outcome.

I plan to continue drawing the presenters, especially the ones who speak Spanish and have Celia translate (because I am given more time), as well as those who have a distinctive look, a unique look that would be fun to capture.

As I said before, there is a magic when drawing people. One line after the other slowly starts to create a life. There is an amazing feeling when all of a sudden one line makes it seem that the person is staring right back at you, ready to tell you their story. That’s what I hope for when I draw. I want it to be more than a face, but a person with a history, something they want shared.