“Rocking back and forth with the lake waves as they reverberate off the metal sea walls, I remember how small and vulnerable I am by myself in this kayak. After 10 days of tent camping, canoeing, and eating food made my fire, I am exhausted. During the trip, we got soaked by rain, showered by sunlight, and immersed in place-based learning; what a ride it has been. We are coming up to the end of the channel walls, and I can see large waves to the left, and calm seas to the right. We are on the left side of the channel and must row to the right to keep from tipping into Lake Michigan. We do so successfully, and we reach the shore. We have made it!! We all rejoice and run back into the lake to cleanse ourselves from a week of hard work and learning. It was then that I knew I wanted to connect more people with the land around them.”

This reflection written by Bekah Schrag, a 2016 participant in the Sustainability Leadership Semester (SLS), is one testament of many that illustrates how the SLS inspires students to bring human communities and the environment together.

As students take courses at Merry Lea, work on applied projects and go on weekly field trips to meet local stakeholders, thematic connections to water and the watershed are woven throughout to help frame the SLS program.

Students come to know and experience a watershed both ecologically and socially as they canoe, study freshwater ecology in class, and meet diverse experts and community members nearby.

So, of all the ways to frame sustainability, why is water the backbone of the SLS program?

Water Transcends Boundaries and Forms Community

Everyone interacts with water. Daily we drink, cook and flush our toilets with water. Recreationally we fish, boat or photograph water. Economically businesses such as farming, water quality engineers and other careers are sustained by water.

Yet as we often engage with water individually, it is also an opportunity for community-building. “Water is a universal uniter, both literally and figuratively,” said Tom Hartzell, coordinator of residential undergraduate programs and environmental educator at Merry Lea.

Because of the accessibility and universality of water, it is an exemplary gateway for understanding the complexities of stewardship in the broad field of sustainability. It is a useful tool as both a model for learning and a tangible ecological system to explore in class.

Because of the accessibility and universality of water, it is an exemplary gateway for understanding the complexities of stewardship in the broad field of sustainability. It is a useful tool as both a model for learning and a tangible ecological system to explore in class.

“Sustainability as a discipline is a huge, diverse, complex way of understanding and working within myriad systems that govern our lives. Setting our watershed as the context for observing and comprehending those systems makes it a bit more practical and less overwhelming,” explained Hartzell.

Much like other natural systems, water flows beyond political boundaries. Water illustrates the need for transcending boundaries within environmental policy and management, thus expanding the definition of who is a stakeholder.

“Literally, the water flows from one community to another, carrying with it pollutants and other manifestations of mismanagement or, more hopefully, arriving clean and clear as a result of responsible and thoughtful stewardship.”

“We enact policies for our towns and city, but the air from one city doesn’t stay in that city and the water flowing through a town doesn’t stay in that town,” said Lisa Zinn, former director of the SLS from 2013 to 2016.

“In order to help students understand this challenge for sustainability, we wanted to think about the regional scale, not in terms of states or counties, but in terms of a watershed.” When the Goldilocks of sustainability searches for the right geographic scale, one city is too narrow, global is too broad, but a watershed is just right.

In the SLS program, water simultaneously breaks down neat boundaries while redefining a “sense of place,” according to Hartzell. Not only do students come to intimately know the St. Joseph watershed during the canoe trip, but they also have meaningful interactions with local residents in the nearby Maumee and Wabash Watersheds of Fort Wayne, Ind.

“Water stewardship…can bring a lot of diverse folks to the table. Helping our students understand water and its different forms of power feels like a critical lesson we can offer here,” said Hartzell. Knowing the watershed’s inhabitants – from professionals to migrating waterbirds – and hearing diverse perspectives helps ground students in the place.

“Water stewardship…can bring a lot of diverse folks to the table. Helping our students understand water and its different forms of power feels like a critical lesson we can offer here,” said Hartzell. Knowing the watershed’s inhabitants – from professionals to migrating waterbirds – and hearing diverse perspectives helps ground students in the place.

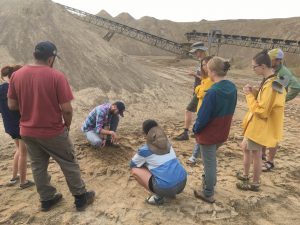

This ability to witness all sides of a particular issue was described by Laura Meitzner Yoder, the first director of the SLS from 2011 to 2013. “A memorable contrast was visiting a gravel pit [on a field trip] and having students get quite excited by the commitment this miner had to sustainable practices, versus a solar company that they all expected to be the pinnacle of sustainability but was actually not that interested in more than the financial gain of the work.”

Water is a Gateway for Sustainability

The results of using water as a lens into sustainability is itself a headwater for further transformational learning: experiences and learning in the SLS “all flow together, building and growing like a river,” described Zinn.

“Even though I knew that an immersion experience like SLS was going to be a powerful way to do education, I was unprepared for how incredibly transformative it was for all involved, including the professors,” she said.

Concepts and strategies that students learn, apply not only to water management but also agriculture, energy, social justice, education and more. Classes, field trips and discussions move students beyond just learning about an issue to “wrestling with it and synthesizing it in a multi-disciplinary way,” according to Zinn.

Concepts and strategies that students learn, apply not only to water management but also agriculture, energy, social justice, education and more. Classes, field trips and discussions move students beyond just learning about an issue to “wrestling with it and synthesizing it in a multi-disciplinary way,” according to Zinn.

The students in SLS develop personal leadership skills that they strengthen through everyday community living and hands-on projects with partner organizations.

“Living in a community shows what leadership looks like, as I’ve learned that leaders need to consider outcomes for the whole of a group. Everyone has a chance to lead and show their strengths,” said Hannah Guthrie ‘23, a sustainability studies major and current student in the SLS.

Another articulation of leadership development begins “with admitting our own awareness of our shortcomings and imperfections in sustainability,” said Meitzner Yoder. “Any group…committed to sustainability is going to have a spectrum of people with strong commitments – for example, vegans who use synthetic chemical-containing personal care products alongside carnivorous locavores who pay a lot of attention to local food sourcing; those who prioritize affordability and those who prioritize farmworker justice; and everything in between.”

“So, it’s a very productive, humbling part of opening ourselves to community growth and sharing, to admit that we don’t know all the answers and we all fall short of where we’d like to be on things that really matter to us.”

And yet despite our shortcomings – or maybe because of them – hope and resiliency continue to be instilled in the SLS program as students explore and enact change efforts around them.

“The experience I had with SLS transformed me to think deeply about my impact on the land around me, and question how I unconsciously influence the world around me,” wrote Schrag. “I understand now how we are all beings on this Earth, and we all deserve respect. Moreover, SLS taught me that even though I may feel as small and vulnerable as I did in that kayak, when we work together as a community, we can enact great change.”