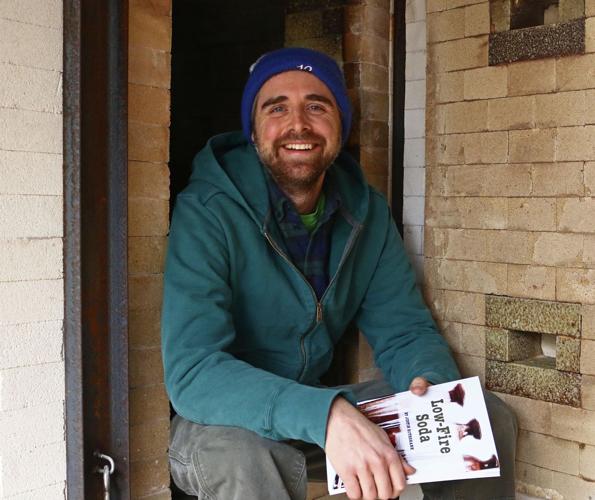

GOSHEN — Justin Rothshank wants to start a conversation.

The Goshen clay artist is sitting inside his rural home studio, his wares lining the surrounding shelves and scattered among multiple tables. Visible from the room’s window are two of his kilns — one gas-powered and the other, wood-fired — amid stacks of bricks, a utility ATV, wood piles and assorted equipment.

Beside the nationally lauded Rothshank are copies of his debut book, the 132-page “Low-Fire Soda,” released Feb. 20 alongside a separate downloadable video component.

“I recognized there wasn’t a lot published on this topic, specifically, on this glaze temperature,” he said. “So, we’re talking about a glaze range from about 2,000 degrees to 2,050 degrees, which is a pretty narrow glaze window. There’s a lot of commercially made glazes that you can go into the store and buy a bottle or bucket of glaze that fires at 1,800 degrees or that fires at 2,100 degrees. But there’s nothing in that middle range, and there’s not a lot of recipes out there, so there was a recognition that this could be a start to that conversation, too.”

“Low-Fire Soda,” he said, is specifically about atmospheric firing earthenware in atmospheric kilns (health and safety, recipes and strategies are also covered).

Translation: electric kilns are like giant toasters — plug it in, hit a button, take the clay to 2,000 degrees, fire it and the glaze matures, he said. Pretty straightforward, as Rothshank has a general idea of the outcome following roughly 20 years of experience.

With atmospheric kilns — gas, wood or oil — carbon is involved.

Burning a fuel adds to the atmosphere, which changes the color of the glazes, he explained. Additives such as salt, soda and potassium can contribute to the atmosphere and act as variables in the process.

“What I’m looking for are those variations in color,” he said. “It’s all based on how much soda hit the surface and how much carbon penetrated the surface, and those variations are what I find appealing.”

For adding salt, Rothshank employs his “burrito” technique, wrapping the material in newsprint and placing it strategically inside the kiln depending of the batch’s needs.

Using potassium pellets twice the size of peanut M&Ms, he dissolves them in water and sprays the pots through multiple holes in his kiln.

Mixing baking soda and soda ash, he’ll frequently apply the spray method as well.

“Typically, earthenware is fired to a lower temperature than porcelain or stoneware. So that has often been done recently in an electric kiln, and so there’s not a lot of nuance to the surface of earthenware,” he said. “This book is about firing earthenware in these other kilns to a much lower temperature and experimenting with surface treatments in that way.”

Rothshank began paving his path to authorship, somewhat unknowingly, about 10 years ago during the construction of his backyard wood kiln.

“When I built my wood kiln — it’s a two-chamber kiln — I built a chamber that allowed me to do this kind of research. And this was long before I had any thought of writing a book. It was just something I was interested in testing. There was a long time I was experimenting with this,” he said.

Five years passed before he built a second kiln to continue research work, so he could fire more often.

About two years ago, he floated the idea to his publisher — The American Ceramic Society — and started researching in earnest.

“At that point was when I started calling other artists and recording information from them and recording my own research, too,” he said, noting the book has around 15 contributors offering expertise in areas such as glazing, which, he admits, isn’t his main strength.

Cups by Goshen clay artist Justin Rothshank are lined in a row.

It took a year to collect shared information and notes, about three months to draft the manuscript followed by four or five months of editing and design.

“There hasn’t been a lot of people doing this process over the years because contemporary ceramics had shifted to stoneware and porcelain,” he said. “But now, with a push toward more surface-decorating techniques — which can be easier to do at lower temperatures — with a push toward green energy and the cost of labor and energy going up over the last 25 years, firing pottery to a lower temperature is more appealing. You use less gas, less wood or less electricity. It takes less time, takes less labor, so it costs less to produce it and it’s equally as durable.”

Less labor also equates to more time for Rothshank in his family-man role, a husband to painter-illustrator Brooke and father of three.

“So, my appeal, especially for this research, was I can light my kiln before I take the kids to school in the morning, and when I need to go pick them up, it’s done,” he said of the six- to seven-hour firing process.

Rothshank made clear a point for prospective readers — it’s a niche topic, and those without a clay background won’t have a reason to buy the book.

“It’s a technical book for people interested in a specific genre of pottery. But that being said, there’s a broad audience within the clay world for that information,” he said. “And I think it’s applicable in a number of ways, so I tried to write it that way.”

Plans call for possible local distribution of hard copies; “Low-Fire Soda” is currently available for order online and through the artist directly.

“It’s awesome to have the book, the hard copy, that I can show people,” he said.

“From a personal standpoint, it just came out a couple of days ago. I’m really excited to hear from other people what they think.”