|

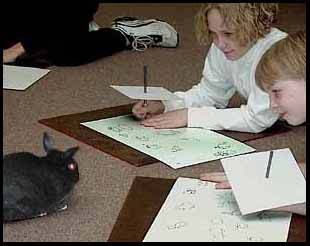

The above illustration is typical of a kindergarten child's uninhibited pre schematic drawing of herself. Most five year olds are totally confident that they can draw, sing, and dance. Tragically, within three or four years this child, if she is typical, will experience a crisis of confidence. She will no longer feel competent or creative. As teachers, we are often partly to blame for the diminished inclination to be creative as children become socialized and aware of their own limitations. WHY CARE ABOUT IT The world needs more and more compassionate creativity to solve difficult problems confronting us. Creative people do not have answers, but they habitually question the status quo and think about alternatives and improvements. They discover and invent possible answers. They habitually ask better questions. They have optimism. When combined with empathy and compassion, creativity is bound to be a force for good. Teaching creativity to everyone is vitally important if we desire a good life for all. Creativity is typically seen as an inherited disposition. Many teachers and parents are not convinced that creativity can be taught. They tell me that kids either have it or they don't. I disagree. I see creativity in all kids with healthy brains. I think of teaching creativity beginning with the day of birth or even sooner. Infants have natural ways to attract attention when they have needs. They learn what works to satisfy hunger, thirst, comfort, affection, entertainment, and so on. If we actively engage with an infant with baby talk and other forms of interplay, the child is motivated to seek more engagement and enjoyment. The child begins to feel more empowered and is more apt to adapt to seek new experiments and learning experiences. In many cultures some families and most schools use a lot of negative behavior management. If children grow up in a highly controlled environment with too many prohibitions, only a small percentage of them manage to persistent and retain their natural creativity. Most of their neurons and thinking habits that would have developed to make a creative mind have been pruned. Their natural tendencies to be adventuresome, experimental, and creative become suppressed. There may always be a very few highly creative who can resist the drill and kill educational methods and the excessive prohibitions of controlling parents. Tragically, the majority of children give up and accommodate. They abandon their imaginative and creative curiosity about life in favor of more secure, but imposed and programmed kind of thinking habits. They accept answers from their instructors as correct (without enought thought). When this happens many good ideas are missed. We risk injustice by manipulation. History is full of examples of leaders who have gained followings and supporters based on very defective ideas. When the masses are both educated and creative, mass tragedy based on false fundamental beliefs systems is less likely to take hold. Classrooms that insist on total conformity without asking for independent ideas are likely to produce citizens who are best suited to cooperation with those who seek to control in order to subjugate them. When only a few are creative, they are able to impose too much control on those with learned helplessness. I write as an art teacher for many years. While being a successful visual artist today assumes a high level of creativity, I think parents as well as teachers in every area need to reflect on what they are doing that tends to foster or hinder the creative critical thinking. Anything as crucial as creativity needs to be taught in every learning domain. Creative readers, whatever they teach, coach, or nurture, will recognize their own lessons and projects in what I describe. In the development of the human mind, the ability to imagine and test our scenarios is among the most advanced of all human traits. Why would any teacher want to ignore or even squelch the imagination and ways to discover truth, goodness, and beauty? WHEN IS FREEDOM A BAD IDEA?Surprisingly, I see the least imaginative work being produced when a teacher gives instructions and says, “In this lesson you can use any topic you want to.” Or, “In this lesson you can work in any media you like.” Even in the case of students whose work seems quite imaginative and creative, if I know the student, I often find that the work is merely a rehash of that student's previous success. We are naturally creatures of habit. Our natural way to learn is by imitation. Students imitate their own success and they imitate their peers. When allowed to do what we want to do, we are likely to revert to whatever we previously found enjoyable and/or successful. This amounts to what I call, “another one of those” artworks. Sad as that is, the worst part is that the creative process is not being learned. Limitations can be designed to require creativity. Requirements in an assignment are limitations that force new solutions. They limit the realm in which one is allowed to operate, making it easier to focus on a problem or an issue. We can find some useful teaching strategies by looking at how artists generate ideas. What if every project, every assignment, every task, and so on was limited to in the sense that nothing is allowed to be repeated unless at least one thing is intentionally changed. Many artists use a strategy called “changing habits of work.” When artists are feeling like everything is becoming redundant and familiar, they can coax a new idea to the surface. An artist might reverse the order of work, change the medium, change the scale, forbid a certain common component or common solution in the work. Reversing the order might be to color in the negative space in a composition prior to adding color to the positive subject matter. My teacher role is to encourage and reward the kinds of strategies and thinking habits that are more apt to result in imagination and creativity rather than imitation and concurrence with the status quo. My students have the responsibility to learn to apply various creativity strategies. My students should expect freedom to make some of the choices and take some of the risk involved when changing strategies. They need practice in creative problem finding and solving. I should not be creative for the student. However, I can raise questions to produce student self-awareness. I can practice creative ways to nurture student creativity. When students are stumped, I find that it is too easy for me to step in and suggest a known or expected solution. This may not be good. Too many students quickly learn to wait for the teacher's suggestion. As a teacher, I feel that I can remind students of common lists of ways to experiment, and so on, but I should not suggest final solutions. Even when only suggesting solution strategies to try, I try to offer more than one option so the students still need to make a choice. They need to feel ownership in their successes and failures. This being said, I need to allow students to make mistakes. I need to encourage them to learn the strategies used to exploit creative possibilities from unexpected outcomes. Mistakes and unexpected outcomes need to be seen as gifts to our creative thinking. They represent a strategy used to find ideas that would otherwise have never been discovered. They need autonomy to make choices about what seems important. Without student choices and ownership, the student's motivation to be creative is lost. Students who are too directed feel put upon to do as they are told for some external reward, but they are bored and often hate the process. It is not the teacher's role to provide the zinger suggestion, even when it feels like an inspired idea. To do so robs the student of ownership as well as creative problem solving experience. In creative teaching, assignment limitations can provide a way to change the student's habits of work. So long as the difficulty level is reasonable, new experiments can yield new successes. A new approach is learned. When I have a student who complains that this is a limitation, I have to explain the learning theory as the rationale for the limitations. If a student persists, I also tell them that I can accept student proposals that violate the limitations if they propose things that are reasonably creative and somewhat challenging. I often use introductory practice related to the new requirements. These warm-ups are prescribed and not particularly creative. I see them as hands on ways to learn new processes without resorting to a teacher demonstration to build skill and confidence without showing examples. I avoid examples because, like showing answers in advance, it is most likely to reduce the need to practice creative thinking. Hands-on warm-ups can include experiments that lead to self-discovered results.

IMITATION

IS NATURAL - IS IT NATURALLY GOOD? It is urgent in today's world that our students become critical thinkers with strong values. Imitation as a learning style is very limited to accomplish this goal, and when I employ imitation in teaching, I must point out its limitations and I need to supplement it immediately with approaches that require innovation, problem solving, and a critical review process. When I learn by imitation, I may become complacent. Not only do I simply produce “another one of those”, I often fall into “another one of those” projects, lessons, or units of instruction. I may say, “If copy work works well for Chuck Close, who works from photographs, it should work well for me and my students.” Not all repetition and imitation is bad, but repetition and imitation is certainly not creative on its own. Unfortunately, imitation is very habit forming. Many people, when faced with any kind quandry, immediatly look for an expert to imitate, to follow, or to copy. For me to Google an answer before I make any personal effort does not strengthen my problem solving neurons. In too many cases, students develop-solution finding habits that lack confidence in their own problem solving ability. This tendency to follow like sheep allows political leaders too much power to manipulate a majority of citizens to accomplish their own ends. History is filled with tragic examples of populations that have followed leaders because they had never learned to think through the ethics or the consequences of scenarios they failed to imagine. DOES

IMITATION

TEACH SKILLS? WHEN DOES IMITATION TEACH CREATIVITY? This is the story of how I discovered that a student could learn creativity by imitating me. I was working with a preschool girl while she was drawing animals. I asked her questions about her recent visit to a zoo. I asked her which animals she liked. I asked her which animal she would like to draw for me. As she drew, I asked her many open-ended questions. If the animal lacked ears, I did not ask her to draw ears, but I asked her what the animal listens to. When she drew a zebra, it did not have any stripes, but I did not tell her that it needs stripes. I did not ask her if it needed stripes. My questions were less direct because I wanted creative thinking. I asked how to tell whether it was horse or not. She seemed to ignore this question and kept drawing other things without putting any stripes on her zebra. She responded to most other questions by adding more and more details that she remembered. As a preschooler, none of this was realistic looking, but to her it all made good sense as she explained it to me while she was drawing. It was clear to me that she was creating an original drawing based on her memories. However, I could not think of a question that would get her to remember and create stripes without actually mentioning stripes in my question. I was resigned to allow her to draw a zebra without stripes rather than reminding her in a direct way that a zebra should have stripes. As she finished the drawing, I asked her if she forgot to draw anything on her zebra? She looked at it and was very pleased with it. She went to place it with her things to show her mother. Suddenly, she came running back to me saying, "Silly me, I forgot the stripes!" She immediately went to work drawing strips on her zebra while murmuring, "Silly me." I learned that memory and ideas sometimes take more time. Time, patience, and persistence are parts of the creative process. After the zebra drawing, she continued to draw other animals and ended with a drawing of a girl. I continued to encourage her and ask open but slightly indirect and open-ended questions when I noticed missing parts to her drawings. Soon I began to notice that her drawings were including more ideas with fewer questions from me. I listened to her self-murmurs and noticed that she had begun to imitate my open-ended questions. Once she clearly said, "Lets see now, what did I forget? Oh! I forgot the . . ." After asking each question of herself, she would create another feature in her drawing. She had learned a creative thinking habit by imitation. I believe that she and I both learned to be more creative that day. I learned that children could learn creativity by imitating teachers that teach them creatively. When I use good creative problem solving questions, students imitate me and learn to pose creative problem solving questions of themselves. What other creative teaching methods are we are missing? I believe there is an extensive list of methods that creative teachers can develop in themselves. These could be imitated by their students. I believe there are many alternative ways to begin a learning session. In a class discussion with five college senior art students, we were able to list more than 20 different ways to begin an art class. Copy-work

issues Too often, I see copy-work becoming a crutch. Copy-work is a form of artistic self-poisoning addiction. It develops dependency because the student notices that their other work looks inferior to their copy-work. Copy-work becomes a "feel good" addiction because is requires less effort than working form real observation or experience. The main skill being learned is, how to copy. Very littl e thinking is required and few real skills are learned. The part of the brain used for copywork is probably not the same as the part of the brain used to render a drawing from a real object or person. It is one step removed from being a passive spectator. The term "couch potato artist" comes to mind. I recently asked an art teacher how he taught drawing. He said he did some drawing up front and had the students draw the same things. Obviously, this art teacher is not an art teacher and has not learned how to teach children how to learn to observe. They are not learning the skills needed to observe from life and they are not learning creativity. They are learning to copy a teacher, which is not much different than learning to copy from another artist or from a photograph. Would it not be much better to use this class time for actual observation and rendition skill development? Good art teachers know how to teach real observation. Those who haven't bothered to learn how to teach observation skills might be called "pseudo" art teachers. Who needs them? It would be cheaper to hire a supply clerk to assign copy-work. Several years ago I was honored to have a visiting Chinese Scholar in one of my college art classes. He is a university English teacher in China and was here as part of our exchange program as a way to improve his conversational English. After class one day we were talking about teaching drawing to children. He shared that in China the teacher taught drawing by drawing on the chalkboard to show the children how to draw each thing. He illustrated it with a stereotypcial cat symbol starting with a circle, adding triangle ears, ending with the whiskers and curved tail. I am sure that this is changing in parts of China, but philosophically, a society that values conformity above individual creativity and choice making probably should teach drawing as a series of prescribed symbols rather than teaching actual observation, thinking, feeling, and interpretation skills. My own first grade teacher was quite competent in drawing from memory and imagination. She had been taught to create a large drawing with colored mural chalk. We were each asked to copy her picture with our crayons. Her pictures, as I recall them, reminded me of stereotypical calendar landscape scenes of places we dreamed of visiting. Copy-work is very common as a learning method among self-taught artists. Their definition of art is somewhat simplistic. They are seduced by the look of art and do not understand the creative aspects of the process. They are producing within a very limited realm. To them, if it looks like art, it must be art. Untutored artists do not notice their own mistakes. They may feel that there are mistakes, but they cannot identify the mistakes. As a result, their work may be charming, naive, and quaint. It often looks creative by default. When these artists start working with a teacher their artwork often appears to get worse and worse. Many get totally frustrated and turn away from their "art". When they are taught to recognize their mistakes they loose the joy. See footnote5 for some ideas to succeed with self-taught artists. Of course some self-taught artists do not copy. Some are very creative.

Repeated practice is essential to learn skills. Practice makes things easier, builds confidence, and enhances quality. Similarly, review is essential to learn facts like artist names, the look of their style, vocabulary about art, and so on. These are important aspects of learning art, but they are not as useful in today's world as the ability to be critically aware, inspired, innovative, and responsive problem solvers. It may be gratifying and entertaining to reach a virtuoso level of performance, but without critical thinking and creative strategizing, it is a hollow victory. Yes, in every area of expertise (not just art) most of the best examples of great creativity do come from those who have achieved knowledge and skill in the area, but skill and knowledge alone are not creative. Somehow, great minds must become experts while retaining and developing their creativity along with their knowledge and skill. Image

flooding issues There are several issues with image flooding? Some art teachers have become quite addicted to this seemingly natural way to show the "look" of the expected outcomes. Yet when pressed, they cannot explain any real rationale for the assignment. They cannot define the problems being presented. They are inarticulate. They may even say, "Art is non-verbal." Indeed, as Suzanne Langer contends, ". . . the import of an art symbol cannot be paraphrased in discourse."4 (p 68) This is true enough. However, teaching art is very verbal. Langer is extremely verbal. Yet, teachers who fail to explain verbally what they are attempting to teach still think of themselves as art teachers. I am not saying it is impossible, but fostering creativity is hard to do unless the teacher understands the nature of artistic creativity well enough to be articulate about it. Therefore, teachers that use image flooding as a substitute for the clear articulation of issues and concepts will seldom succeed in fostering creativity. The nature of imitation is too powerful as an instinct, and too much the opposite of creativity. The instinct to imitate can easily overcome our instinct to imagine - which can take a lot more effort. The second issue I see with image flooding, is the lack of creative integrity that is fostered in the learner. As a student is easier for me to be just creative enough to make the teacher think I am being original. This teaches me to borrow and recombine things in devious ways so nobody will recognize who I am mimicking. In true creativity I would have to bring something into the mix from my own life experience. Image flooding does not require this and does not foster this. Image flooding shows me examples from other lives so I need not bother with my own life. In the end the art is also less mine and more other's. True creativity happens when intuitive imagination brings forth the previously unknown and unimagined. Clever combinations of imitated ideas might look creative, but are they? As a learner, I am even being deceived about the nature of creativity. The third issue I see with image flooding is that students who might otherwise be naturally creative will find it much harder to access their own rich store of subconscious experiential store of experiences and ideas. Even highly creative students can be insecure and very suggestive. Once we an see an image or an idea, it starts to cover up our own ideas that were trying to emerge. These outside images from other artists become insistent tunes impossible to shake. In this way image flooding actually drowns (suffocates) individual creativity before it has a chance to swim on its own. Teaching without image flooding Once students tackle an assignment creatively, they will naturally be curious to see what others have done related to the problem they have struggled to solve. When studying a master, they will not only be interested in seeing the end product, but they will be open to learn about the master's creative methods. We do not only study the look of the work, we try to figure out why the artist did it that way. In this kind of problem solving, students find historical evidence from research to confirm ideas about the creative methods used. If we want to foster student creativity, we can teach the art history as review and reinforcement of the art lesson - not as a pattern for the art lesson. The creative work happens first. The related history is studied after the personal creative work. In addition to ending class sessions with historic and contemporary examples, I can also teach art history as a discrete body of knowledge without using it as example work for a particular creative problem. While this may not directly practice creativity, it still gives students knowledge about and appreciation for the creativity of other artists. It may still provide good information about creative processes and methods used by artists to achieve the artworks we are studying. For those interested in integrated learning, students can also be encouraged to begin with art about their own experiences related to a cultural concept. After doing the artwork, they can study similar concepts in science projects, social issues, and so on. When working with kindergarten children in a religious education (Sunday School), I might start with a discussion of various ways they work as helpers in their families. Then basing their work on these experiences, they create drawings. This is followed by a story from a religious text that tells about how somebody was a helper in the story. I do not use art to review other subjects. This makes art into a mere tool to help remember something else. This is not creative and it would not be in keeping with my understanding of art. Of course other school subjects come into the artwork with

integrity

when students become knowledgeable and deeply concerned about issues

related

to other subjects. Some very creative social issue artwork could

emerge when students experience things like prejudice, pollution, drug

overdoses, drunk driving, and other things they and their friends

encounter. HOW

ARE CREATIVE IDEAS GENERATED? For related thoughts, see Planning to Teach Art Lessons. Ultimately, every lesson is less product oriented and more for the purpose of learning the process of artistic creativity. Also see: Art Rubric Creatively productive people use a number of methods that teachers can

learn from. When I give an assignment that starts with list making, I have them first work individually. Then I might ask them to form groups of three or four. Generally, I try to use grouping criteria to get as much diversity of skill, interest, and background as possible in each group. Using a group of diverse experts is known as synectics. Students may not be experts, but they are each encouraged to contribute from their unique experiences. I want them each to present their ideas to the group and ask for help adding features, new ideas, and so on. I want them to take each others listed ideas and add them to their own ideas to see if still more or better ideas develop. In today's world, most tasks require complex solutions that only collaborative efforts can achieve. Beginning in elementary grades students can learn to be collaboratively creative learners and teachers of each other. After significant effort to get long lists, fine-tuned ideas,

and so

on, they are asked to rank all ideas according to several

criteria.

Criteria depend on the project, but they might sort them from

innovative

to common, from simple to complex, from beautiful to ugly, from useful

to non-functional, from durable to temporary, from precious to cheap,

and

so on. Consider

opposites Consider

practice Direct involvement with materials and processes Thinking process rather than product To teach the creative process, we avoid posting charts that gives answer unless the students themselves have invented the charts. I might ask them to do experiments to figure out how to mix a color that will match a color that they select on a spot on a still life object has been placed on a table in the room. I like to select things from the garden or produce market that have colors unlike any of the student's paints. Their paints for this might include only primaries and neutrals. Their questions and experiments need to consider hue, value, intensity, lighting, color temperature, and so on.. As in math, you could ask them to show their work--not just an answer based on one guess. False starts and incorrect guesses are okay, but not an end-point. Real experiments often result in wrong answers at first. Each step might include a note about how it was done. In the end, a small color chip can be attached to the actual still life to see if it appears to blend in or disappear. Unlike math, there are many ways to approach this problem. When math is involved in an art project, I like to see the same answer derived in at least two ways. This not only encourages creative thinking, it improves accuracy. In a reverse of the above color matching process problem, students could experiment to create the most contrasting color to use as the background color. Now the end product becomes more subjective and individualized. Colors have different kinds of contrasts including hue, tone, temperature, and saturation. With an open option for how to produce contrast, students will make discoveries in some proportion to how much experimentation they are willing to do and/or how asvanced and aware they have become. In another vein, color experiments can be compared to look for relationship that evoke certain emotional effects such as anger, love, sweetness, tartness, and so on. In one process centered assignment I ask students to represent the relationships in their own family by using abstractly shaped pieces of painted paper that they paint and cut. When finished, another student unfamiliar with the family being represented has to attempt an interpretation. For the sake of privacy, the class is assured in advance that actual explanations would not be required from the makers. Since no families are perfect, a follow-up assignment might be a variation on the first where an imagined idealized family is composed by the same method. Some additional ideas on teaching students ways that artists generate their art ideas is included in The Secrets of Generating Art Ideas: An Inside Out Art Curriculum. Consider

assessment

and grading paradigms We can develop more games, assignments, and even tests that give points for unique responses while not counting points for answers that somebody else gives? Bonus points could be given for high quality, beauty, expressiveness, usefulness, artistic importance, correctness, truthfulness, and whatever else is deemed important. We need to stop giving so much credit for redundant facts that everybody already knows. Consider

the tone

and nature of responses to student ideas Consider

the familiar

- avoid exotic content

Recently the shadows that fell on my work from overhead hickory trees became astoundingly compelling and beautiful. This work may not have a huge effect on the history of art and the world, but it is original and it represents a truly creative moment. At first, I was stumped. Not until I became open to my immediate familiar surroundings, did I become inspired and creative.Consider answering questions with questions Many students come the art teacher and ask for suggestions related to their work. How can art teachers avoid becoming the “know it all” that takes ownership of the student's artwork? What are some thinking questions we can ask? How can we reassure them that there are several ways to do it? Art is a search. Art with integrity grows from an honest search. Students will become more creative if they can feel they are the true owners of their work. We can even hope that students will learn how these questions are formulated. It may eventually be possible for the teacher to ask, "What are the questions?" The student will say, "Oh. Yes. I know what to try." Consider answering questions with questions about experimentation Art students have often asked me to give them a suggestion to improve a work in progress. Many times my ego and my pompous personality have simply prompted me to blurt out an answer. I have given my recommendation without even thinking that this could have been a teachable moment. My students learned dependency. Too often I have been the dependency facilitator. Had I been thinking scientifically about teaching creativity, I might have ask the student to design a small experiment relating to something that noticed (without saying what I thought the outcome would be). Yes, the scientific method takes more time in the short run, but if a student learns that they can design experiments to solve their own problems, they have learned not only the scientific method, they have learned one of the important components of artistic thinking and artistic behavior. Ultimately, time is saved because students have learned to figure out how to answer their own questions. They are empowered and creative. Teaching habits are powerful and subtle. Answering questions in the studio class gives me such a feeling of power and is such a hard habit to break. As an artist, I am generally more clever than the student - what an ego trip! During the Dark Ages science was a set of teacher answers. Progress was made when the scientific method began using questions and experiments to check on old answers and discover new answers. We came out of the dark ages when real and careful observation replaced copywork. In science, nothing is assumed to be true because a teacher says so. Too often my art class was taught using Dark Ages dogmatism. Example Caution Many teachers have argued that skills and knowledge are essential prerequisites for the production of art. This belief leads to lots of “another one of those” art assignments with no requirement for innovation. I believe it is much better to include both innovation criteria as well as skill and knowledge criteria. This can sometimes be done concurrently and sometime alternately. It may be helpful if teachers and students become more aware of what is working at “rehearsal” and when they are being asked to “perform” creatively. Both are important, so one or the other should not be an excuse for ignoring the other. Most four and five year olds are naturally creative, but very immature in their skills development. At this age we all understand that it would be ludicrous for us to insist that they be proficient in skill before they are allowed to be expressive. Art teachers are of different minds as what is needed when children begin to notice that they have little or no drawing ability. Unfortunately, some teachers say, “Don't worry, I can't draw either.” Instead of helping them learn to look more closely at their worlds, they devalue learning to observe. They give art assignments that look like art, but require no particular ability. They imitate, they copy, they follows step-by-step assembly instructions, and so on. Along the same lines, some art teachers show formulas from books on “how to draw a tree, a face, or a human figure”. These methods do not teaching drawing competency. They teach dependency. Few children complain because they naturally enjoy imitation and they are mildly rewarded by pretty products. There is no way for them to know that good art teaching could help them with methods that actually teach them how they could learn to draw anything by helping them practice standard observations methods. Of course art and creativity are more than drawing. Art includes many complex questions related to compositional awareness, expressive quality, evocative images, implications and connotations. IS CREATIVITY, DRAWING, AND TALENT CONNECTED? The ability to draw a likeness may seem to be a natural gift or talent for some, but it is actually acquired by practice. Like anything else, some acquire this skill faster and easier than others, but everybody learns it through practice. Nearly everybody can learn to play piano with a good teacher and faithful practice. Nearly everybody can learn to read and write with a good teacher and with faithful practice. The same is true for drawing. These are skills that are easier for some and harder for others. The ones who learn easier and without a teacher in our culture are thought to be talented, but they still learn by practice. Drawing is not dependent on talent, but for many, drawing is dependent on knowing how drawing is learned. Practice does make it easier. Natural propensity is not essential for drawing any more than it is for reading. Many elementary classroom teachers, if asked by a child for help with a drawing, will be told, "Don't worry about it, I can't draw either." Would that same teacher say every say, "Don't worry about it, I can't read either."In our culture we have become absolutely dependent on reading, but only marginally dependent on the ability to draw. This cultural bias that fails to see the basic need to learn drawing helps produce substandard creative thinking ability in the general population. IS DRAWING NEEDED FOR CREATIVITY? Drawing is an extremely useful, if not essential tool used in creative thinking. Drawing is very helpful to most students and adults in the development of all kinds of creative ideas and in problem solving. Imagination means visualization. Learning to draw develops the portion of the brain that visualizes. Visualizing is used in all kinds of creative planning activities including charting, graphing, mapping, planning structures, planning communities, and design of every kind. Creative workers employ drawing and visualization to check out many scenarios before they make decisions. While planning a creative project, drawings are constantly being modified and refined. Creative planners have learned to expect the drawing process to bring out many new ideas that would have been missed otherwise. Drawings allow creative collaborations with non-drawing participants whose creativity is facilitated by the drawings. Drawing for a creative worker is a dynamic conversation with the plan and the other stakeholders. The drawing talks to the designers and the designers responds with new variations until the best possible outcome is realized. I once visited Don Reitz in Wisconsin after he had added an sizable addition to his house. Don was on the art faculty at the University of Wisconsin. He is a very creative potter and sculptor whose work is very expressive, but I do not believe he draws things before making them. The clay itself is his drawing material. He does very expressive work by responding directly to the material. Drawing first on paper would probably deflate his enthusiasm for the actual creative work. When he decided to have workers build an addition to his house, he decided to try the same approach. When the excavator came, they walked around, looked at the site, and decided where to dig, and so on. Everything worked out fairly well with a nice two story addition to his house. However, fairly late in the project they could not find a good place for a staircase between the two floors. To solve this, he had a fairly small spiral kit installed. Had he used drawings, he may have noticed this in time to create a more elegant solution that would allow easier and safer transport of furniture to the upper level. Drawing is not merely a medium of creative planning. Just like clay is the immediate, expressive, and vital "drawing" medium for Don Reitz, drawing on paper can also be a vital, expressive, and creative end product for may artists. When art teachers teach children how to learn observation drawing, they are facilitating creative thinking in many other areas of their lives. When we teach expressive drawing, we are engaged in actual creative thinking and acting. Children need to learn both. Every scribbling child is being expressive almost without knowing it. Observation skill practice can begin fairly young, and at least by grade one. Expressive work should also continue to be nurtured. Without deliberate drawing instruction, only a small percentage of children learn to draw because most children lack the instinct to keep drawing on their own as soon as their critical sensitivities outpace their observation drawing skills. Only a few people would learn to read and write without teachers. Most would give up without teachers or parents to coach this learning. In such a culture, we might say they that most people lack the talent to read and write. That in fact is the culture we now have in many communities in regard to observation drawing. Children do not learn how to learn drawing because they do not have art teachers or they have art teachers who do not know how to teach drawing. In the US about 40 percent of the elementary schools do not have art teachers. This important mind development is missed and much creativity is missed when this tool is abandoned during our development. Art teachers need to help children begin to make visual comparisons and represent them in their drawings. I use lots of open questions that remind children to observe more carefully. I do not draw in front of the students because it encourages them to copy my drawing and they still do not learn to observe. I go over to the thing being observed and carefully point out how to notice things. I ask them to practice drawing in the air while observing before committing pencil to paper. Students are asked to notice contour, size, texture, value gradations, proportions, and every kind of relationship in the thing, person, or animal observed. I ask them to use a pencil at arm's length as a sighting device to compare sizes, angles, and so on. I often encourage the use of touch, and include smell, taste, and sound as motivation and when experiencing the world. I avoid copy work, formulas, and drawing tricks. I do not give answers, but encourage experimentation and exploration to find answers. I provide aides to observation including viewfinders to frame compositions and pencil blinders (a square of tag board with the pencil through it) to to hide the paper and encourage looking at the thing being observed. When mistakes are obvious to the student, I encourage another line before erasing the mistake. "Don't nix it until you fix it." Sometimes three or four tries are needed, but this is learning. The purpose of practice is to make it easy and to make it better. RITUALIZE IT

IS

ART

LEARNED FROM RULES or FORMULAS? Expressive drawing, painting, sculpture, and so on grows out of intense and extensive experimentation with materials and processes, by working slowly and deliberately, by working fast and spontaneously, by combining the methods, and then attending to the results, not by learning any rules of drawing. Imaginative drawing is learned by making many lists or thumbnail sketches of ideas that grow out of experiences – not by copying another artist's surrealistic images. Creativity is learned when learners find out that their risks bring rewards. Formulas imply a safe answer. They encourage sticking with safe systems rather than taking the risk to learn how to learn a new ability. In the US, even the National Standards of Art Education do not list observational drawing as an essential ability or standard. Observation drawing is apparently seen as optional for those who enjoy it. What would happen if writing and reading were considered optional for those who enjoy learning to write and to read? “That's okay, I can't read either” is not commonly heard in the classroom. Too many children shy away from art or find little joy in it because they suffer under the illusion that they are not talented. This is because they have never been exposed to a few simple methods used to practice observation drawing and overcome their childish methods of rendition. Observation drawing teaches us that we can truly trust the truth of our own observations more that what others tell us about truth. Drawing from memories and experiences is a second source of inspiration for drawing. Preschool children who have progressed beyond the scribbling stage, nearly always draw from their experiences. Teachers and parents can encourage and enrich creative self expression and creative thinking habits of young children by asking them relevant open questions (questions with multiple correct answers) while they are drawing. If we want to encourage creative thinking, these kind of questions never suggest or dictate, but they help and encourage children to think of more ideas to include in their work. More of what they know becomes visible in their drawings. The work is also more creative and richer when the experiences themselves have been enriched. For example, if a child has visited a zoo with a caregiver who actively discusses the animals with the child, she is apt to make much more creative artwork related to this experience than another child who visited the same zoo with a passive caregiver. Drawing from the imagination is a third and particularly creative source of inspiration for drawing and other other artwork. Young children have a strong instinct to imagine which seems to decrease rapidly as they go through school. We cannot say for certain why the imagination seems to decrease so much as children age. We do believe that constant pressure to have come up with one right answer, to copy things in workbooks, color in other people's pictures, and similar activities all conspire to discourage creative and imaginative divergent thinking and problems solving. Learning of experiment with art materials in order to see how they create their effects is a good way to encourage creative and imaginative thinking and counteract some of the stultifying influences of becoming cultured and trained to conform. Drawing and other artwork is inspired by three sources that enhance our creativity. They are observation, experience, and imagination. Lesson that are based on rules, copywork, examples, and demonstrations are less apt to encourage creativity. This is not to say that there are constraints. Good teaching has many constraints and limitations in order focus thinking and ensure creativity. Should Art Teachers Teach the Visual Elements and Principles of Composition In

the meantime, there is little harm in working at definitions and

tentative rules so long as we also agree to live with uncertainty and

change. Rather than teaching the elements and principles as

predetermined truth, a teacher interested in fostering creative

thinking might be well advised to ask students to experiment in ways

they might postulate and arrive at compositional principles on their

own. Just as education is better when we learn invention than how to

make previously invented products, it is better to learn principle

finding and verification rather than learning principles determined by

dead experts at another time and place. It is very creative to ask

students to define a set of principles that can be used to assess their

own work. It is creative to ask students to figure out how the old

standard elements and principles might have been determined? As in

life, if there are rules, they are more likely to be things like: pay

attention, make comparisons, verify, be skeptical, look before you

leap, and so on. The traditional design principles can guide, but

not determine the process, and they certainly do not determine the art

product.- top of article Teach creativity by giving TIME FOR THE CREATIVE PROCESS In organizing the sequence of mind training and creativity training lessons, are there ways to ritualize and focus advance preparation, discussions, questions, and sketching sessions that promote thinking, looking, more sketching, dreaming, and idea development for lessons that are coming in the future. Are there ways to encourage and reward the keeping track of art ideas that come to mind at unexpected times? When I leave my studio my hands-on work is interrupted. I may even leave because I am experiencing a block, but my mind keeps working - my homework is continuing with the expectation that my mind will inform me of the next move. Good teachers prepare their students so that when their students leave the classroom their minds are prepared for homework that is no work. They expect to get ideas at unexpected times. This is homework that is no work in the traditional sense. Good teachers understand the surreal powers of subconscious minds, of imagination, and of creative thinking habits. The creative process includes preparation, incubation, insight, elaboration, and evaluation. Classrooms that include preparation, incubation, and insight might need to juggle two or three projects at once. What are the class rituals and concept questions that get the wheels turning so that dreams and imaginations are ignited. I have often been tempted to use shortcuts such as showing examples of other art to get quick inspiration and information as a substitute for relevant self-referential thinking. But what are the ways to define artistic challenges in ways that to give the students the courage to develop and express their own ideas? This takes time. It means practice sessions, question session, and list making rituals.This means setting aside time that is days or weeks in advance of the actual production to get students focused and thinking. It means programming their minds to do the subconscious incubation homework that helps bring insight to the table when the production starts. We know that homework works best when we develop rituals of accountability and when we make a point of rewarding successes. What are the classroom rituals that give credit and honor to the students when they show evidence of subliminal ideas that have been recorded and brought to class and infused in their creative work? How often do we take class time to investigate the sources of our own creative ideas? As a teacher, how often do I teach “another one of those” lessons? Can I justify it because I am still learning how to teach? As a creative teacher, it is my responsibility to review the results of a lesson or a unit. As I assess the results, it is my responsibility to imagine other ways the lesson could have been taught. It may be a year before I teach a similar unit again, will I remember what needs to be changed? Will I remember to start mentioning it sooner so that my students' subconscious minds start their homework sooner? A creative teacher needs a good system to record ideas for next year? I am thankful for computers to make this easier. For a number of years I had college art students who were required to observe some of the best art teachers in the public schools in our area. My students had to journal their observations. Even though they saw very impressive methods, I required that their notes and ideas include alternative ways of teaching a similar lesson. Also, their journal must include some critical thinking about the pros and cons of “another way” of teaching what they observe. It is fairly easy for apprentice teachers to learn by imitating their model teachers. However, creative teachers go beyond imitating their role models. They go beyond their mentors. They do this by virtue of critical review of their own teaching – by carefully reviewing what happens and then searching for alternative things to try. Creative teachers make mistakes, but but they also search for ways to overcome mistakes. Each time they try something, they review the outcomes and try to imagine ways to make improvements. If I am an uncreative teacher, it may be because I do not feel that I make mistakes. I know I am teaching in the same way I was taught. My instinct to imitate says I am doing okay. I may admit to some bad outcomes, but in my uncreative mind I blame my students for the bad outcomes. I say, “Nobody can teach correctly for every student in a class and certainly I should not be held responsible for an unmotivated or ‘mentally challenged’ student. Students have to do their part.” If I tend to make excuses for what should be changed in my teaching, I will not be a creative teacher. On the other hand, if I have a habit of looking for new alternative methods, I am likely to be a creative teacher.

Considering

colleagues

and bosses If you are an art teachers interested in doing some research on creativity, on learning to draw, or on the relationship of art and learning to think, or some other issue, send me a note. Click here for a list of issues of particular interest to the author. 2 Kotulak, Ronald. "Word Test Used to Spot Creative Geniuses." Chicago Tribune, October 2, 1983, page 1. This article describes research by Albert Rothenberg. 3 Rothenberg, Albert. "Creative

Contradictions"

Psychology Today, June, 1979. Pages 55-79. 4 Langer, Suzzane K. Problems of Art. 1957.

Charles

Schribner's Sons, New York. back to top of article

Other essays by the same author Related reading: Kathleen Cotton. Teaching Thinking Skills

back to top

of article

All rights reserved. This page © Marvin Bartel, Emeritus Professor of Art, Goshen College. Teachers

many make a single copy for their personal use so long and the

copyright notice is included. Scholarly quotations are permitted with

proper attribution.

For permission to make copies or handouts, contact the author

|