Kinetic theory of gases

Read Chapter 11!

Using only a few simple assumptions:

- A gas consists of "billiard-ball"-like particles (or "molecules"),

- There is a function $f(v)$ which is *not* a function of time, such that at equilibrium, the number of particles with speeds between $v$ and $v+dv$ is given by $$f(v)\,dv.$$ [We don't actually need to know *what* the function $f$ is. Just that it's time independent.]

- Pressure is the force on container walls due to the particles bouncing off the walls--due to their change in momentum.

We will find..

- Pressure is proportional to the average kinetic energy of the particles.

- A consequence of these assumptions is the ideal gas law $$PV=nRT$$ if we identify the temperature with the speeds of the particles according to: $$\frac 32 k_BT=\frac 12m\overline{v^2},$$ where $k_B$ is a new constant of nature.

What is pressure?

A search for 'pressure' on photo-sharing site flickr.com turns up this photo

by Kevin Dooley

Isaac Newton's guess was that a static repulsion between pieces of matter was responsible

for this force (per unit area). I'll paraphrase this as: Matter is like Jello, and has a certain 'springiness'. No notion of "atoms" enters into Newton's concept.

Isaac Newton's guess was that a static repulsion between pieces of matter was responsible

for this force (per unit area). I'll paraphrase this as: Matter is like Jello, and has a certain 'springiness'. No notion of "atoms" enters into Newton's concept.

A number of scientists in the 19th century developed a kinetic theory which posits that pressure is due to collisions of constantly moving atoms with the walls of a container..

Though we can't see atoms directly, Brownian motion in which pollen or other small particles seem to jiggle around would seem to be consistent with the idea of constantly moving atoms.

Can we account for pressure, temperature, and even the ideal gas law with a few simple assumptions?

Assumptions of kinetic theory - an ideal gas

- Particles are far apart from each other. That is, typical distances are large compared to molecular sizes, and to equilibrium separations in solids.

A. Greg claims these circles and relative spacings are to scale for He atoms compressed to 1950 atmospheres.

One implication of this is that disturbances in the medium propagate with the typical speed of the molecules. So, the speed of sound ~ a typical speed molecular speed. In air at STP, the speed of sound ~ 700 mph.

- The only intramolecular forces are associated with collisions.

- Collisions are elastic.

- Molecules are evenly spread in space throughout a container.

- Molecular velocities are evenly spread in direction.

- We have a large number of molecules. We can use statistics without worrying

too much about inhomogeneities.

This is where we're going:

Annie Spratt, unsplash.com.

From Newton's law: $$F=ma = m\frac{d}{dt}v=\frac{d}{dt}(mv) =\frac{d}{dt}p.$$ Many molecules are bouncing off the walls of their container. A small area of the container wall is $dA$. Pressure acting on any small patch of the container wall is the total force=change of momentum of the rebounding molecules divided by the area of the small patch of wall: $$P = \frac{dp/dt}{dA}=\frac{dp}{dA\,dt}.$$

This will depend on...

- the the speed of every molecule,

- the angles of approach of every molecule to a wall of the container,

- the statistical distribution of speeds and angles,

- ...

Statistics

At equilibrium, we shall assume that there is a time-independent function, $f(v)$, such that $f(v)\,dv$ is the fraction of all the molecules with speeds between $v$ and $v+dv$. Or you can think of it as the probability that a particular molecule has a speed between $v$ and $v+dv$.

- It turns out that we will *not* need to know the exact functional form of $f(v)$. Yay!

The fraction of the molecules with speeds between 0 and $\infty$ is 100% = 1.0, that is: $$\int_0^{\infty} f(v)\,dv=1.$$

Since $f(v)\,dv$ is a fraction (dimensionless), think of $f$ as having units of (unitless) probability per unit speed, or the same units as

$v^{-1}$. You might think of it as "probability per

speed interval".

The mean speed is

$$\overline{v} \equiv \int_0^{\infty} vf(v)\,dv.$$

The mean square speed is $$\overline{v^2} \equiv \int_0^{\infty} v^2f(v)\,dv.$$

This is usually something quite different from $\bar{v}^2$.

The $n$th moment of the probability distribution $f(v)$ is:

$$\overline{v^n} \equiv \int_0^{\infty} v^nf(v)\,dv.$$

The root mean square speed or rms speed is: $$v_{rms}=\sqrt{\,\overline{v^2}}.$$

Molecular flux

How many molecules hit a unit area--a portion of the wall of a container of gas--in a unit time? This is the molecular flux, $\Phi$, which has units of [molecules]$/(m^2\cdot s)$.

${\frak n} = N / V\ $

is the density of molecules (number

per unit volume), written as ${\frak n}$ to distinguish it from $n$ (kilomoles).

$v\,dt$

is the maximum distance away from $dA$ that a molecule moving with speed $v$ could be, and still reach $dA$ within a time $dt$.

$(dA\,\cos\theta)(vdt)$

is the volume of the slanted

cylinder shown.

$f(v)dv$

is the fraction of all molecules with speeds

in the range $v$

to $v+dv$.

If *all* of the molecules in the speed range $v$ to $v+dv$ in the slanted cylinder were moving in the direction $-\theta, -\phi$ towards $dA$, they would all hit $dA$. This number of molecules is: $${\frak n}f(v)dv\,dA\,\cos\theta\,vdt=\color{#00f}{{\frak n}v f(v) \cos\theta dv\,dA\, dt}.$$

But only a fraction of these atoms are actually headed in the right direction. Now, we calculate that fraction (from symmetry) by asking what the chances are that a molecule is moving in a direction with spherical coordinates between $\theta$ and $\theta+d\theta$ and between $\phi$ and $\phi +d\phi$. This probability depends on $\theta$ and $\phi$...

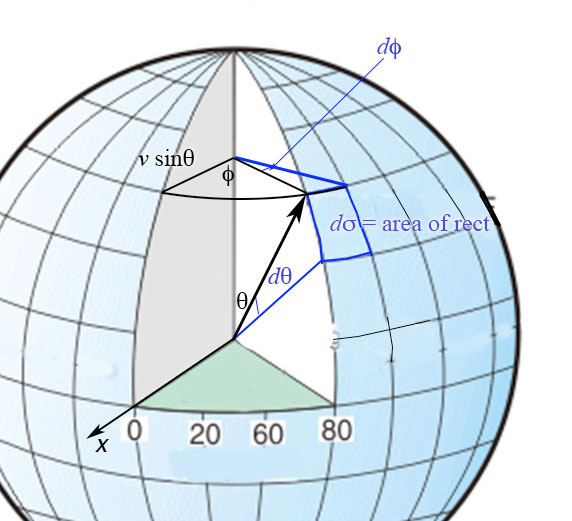

Since the directions of the velocity vectors are evenly spread over all directions, the fraction of molecules with directions between $\theta$ and $\theta+d\theta$ and $\phi$ to $\phi+d\phi$ is the same as the ratio of the area swept out in the figure to the right $d\sigma=(v\cos\theta\,d\phi)(v\,d\theta)$ divided by the total surface area of the sphere of radius $v$ which is $\pi v^2$.

Since the directions of the velocity vectors are evenly spread over all directions, the fraction of molecules with directions between $\theta$ and $\theta+d\theta$ and $\phi$ to $\phi+d\phi$ is the same as the ratio of the area swept out in the figure to the right $d\sigma=(v\cos\theta\,d\phi)(v\,d\theta)$ divided by the total surface area of the sphere of radius $v$ which is $\pi v^2$.

That ratio is: $$\frac{(vd\theta)(v\sin\theta\,d\phi)}{4\pi v^2} = \color{red}{\frac{\sin\theta\,d\theta\, d\phi}{4\pi}}.$$

So, the total number of molecules in the cylinder oriented in direction $\theta, \ \phi$ with the right speed $v$ to cross $dA$ in time interval $dt$ is $dN(v,\theta,\phi)$. $$dN = \color{#00f}{{\frak n}v f(v) \cos\theta dv\,dA\, dt } \color{#f00}{ \frac{\sin\theta\,d\theta\, d\phi}{4\pi}}.$$

The flux is the number of molecules (with speeds between $v$ and $v+dv$) crossing $dA$, per unit area, per unit time. $$d\Phi (v,\theta,\phi) = \frac{dN}{dA\,dt}.$$

To find the total flux, we need to integrate over all the cylinder directions $\phi$: $0\to 2\pi$ and $\theta$: $0 \to \pi/2$, and over all the speeds $v$: $0\to \infty$: $$ \begineq\Phi &= \frac{{\frak n}}{4\pi}\int_0^{\infty} v f(v)\,dv \int_0^{\pi/2} \cos\theta \, \sin\theta\,d\theta \int_0^{2\pi} d\phi \\ &= \frac{{\frak n}}{4\pi}\int_0^{\infty} v f(v)\,dv \, \frac 12\,2\pi = \frac{1}{4}{\frak n}\overline{v}. \endeq$$

[Where I've used $d(\sin \theta) = \cos\theta\,d\theta$ to write... $$\begineq \int_0^{\pi/2}\sin\theta \cos\theta \,d\theta &= \int_0^{\pi/2}\sin\theta\,d(\sin\theta)\\ &=\int S\,dS=\frac{S^2}{2}\\ &=\left.\frac{\sin^2\theta}{2}\right|_0^{\pi/2} = (1^2-0^2)/2=1/2.\endeq$$ ]

Pressure in the kinetic theory

From Newton's law: $$F=ma = m\frac{d}{dt}v=\frac{d}{dt}(mv) =\frac{d}{dt}p.$$

If many molecules are bombarding a small area $dA$, the pressure is the total force(=change of momentum) per unit area: $$P = \frac{dp}{dA\,dt}.$$

Consider

a molecule bouncing elastically(=no change in kinetic energy) against a wall: $|\myv{v}| =|\myv v'|$ and

$\theta=\theta'$. The change of momentum of the molecule is perpendicular to

the wall, of magnitude:

$$mv\,cos\theta -(-mv\, cos\theta)=2mv\,cos\theta.$$

Consider

a molecule bouncing elastically(=no change in kinetic energy) against a wall: $|\myv{v}| =|\myv v'|$ and

$\theta=\theta'$. The change of momentum of the molecule is perpendicular to

the wall, of magnitude:

$$mv\,cos\theta -(-mv\, cos\theta)=2mv\,cos\theta.$$

To get the total change in momentum for the area $dA$ in the time interval $dt$, we should integrate this momentum change, a function of $v$, over all velocities and directions... $$\begineq dp &=\int 2mv\,\cos\theta\,dN\\ &=\int 2mv\,\cos\theta\, \color{#00f}{{\frak n}v f(v) \cos\theta dv\,dA\, dt } \color{#f00}{ \frac{\sin\theta\,d\theta\, d\phi}{4\pi}}\\ &=\frac{2{\frak n}m}{4\pi}\, \int_0^\infty v^2f(v)\,dv\, \int_0^{2\pi}d\phi\, \int_0^{\pi/2}\cos^2\theta\sin\theta\,d\theta\,dA\,dt\\ & =\text{...}\\ & = \frac{1}{3}{\frak n}m\overline{v^2} dA\,dt.\endeq$$ using this result for $\int$...$d\theta$.

Using the expression above for $P=\frac{dp}{dA\,dt}$: $$P=\frac{1}{3} {\frak n} m \overline{v^2} =\frac{1}{3} \frac{N}{V} m \overline{v^2}.$$

Multiply by $V$ to get something suggestive of the ideal gas law: $$PV = \frac{1}{3} Nm \overline{v^2}=\frac{2}{3}N\left(\frac{1}{2}m\overline{v^2}\right).$$

We can write this even more suggestively as... $$PV = \frac{N}{N_A}R\left(\frac{2}{3}\frac{N_A}{R} \frac{1}{2}m\overline{v^2}\right)=nR\left(\frac{2}{3}\frac{N_A}{R}\frac{1}{2}m\overline{v^2}\right).$$

Knowing, empirically, that the ideal gas law is $PV=nRT$, it would appear that for our simple, "billiard ball" model of gases, the quantity in brackets must be the "temperature", implying that temperature is proportional to the average kinetic energy of our billiard balls.

The constants in the bracket encourage us to define a new and useful constant, $k_B$: $$\frac{R}{N_A}=\frac{8.31\times10^3 {\rm J/kilomole\cdot K}}{6.02\times 10^{26} {\rm molecules/kilomole}}\equiv k_B {\rm [J/K]},$$

$k_B$ is the Boltzmann constant, such that...

$$\frac{3}{2}k_BT = \frac{1}{2}m\overline{v^2}$$ ...for a "gas" of billiard balls of mass $m$.

In terms of the Van der Waals equation of state, "non interacting" means no attractive forces between the balls, $a\to 0$ and no hard-core repulsion effects, $b\to 0$. This means that the billiard balls have a vanishingly small volume, so they are effectively "point-like".

This equation further predicts that for a mixture of gases, all at the same temperature, the average rms speed for molecules of a particular chemical species is proportional to $1/\sqrt m$, where $m$ is its molecular weight.

...And that's part of a possible explanation for a solar system mystery:

...And that's part of a possible explanation for a solar system mystery:

- Hydrogen is the most common element in the universe.

- 90% of Jupiter's atmosphere is $H_2$,

- 75% of Saturn's,

- But 0.000055% of Earth's...??