Half-life

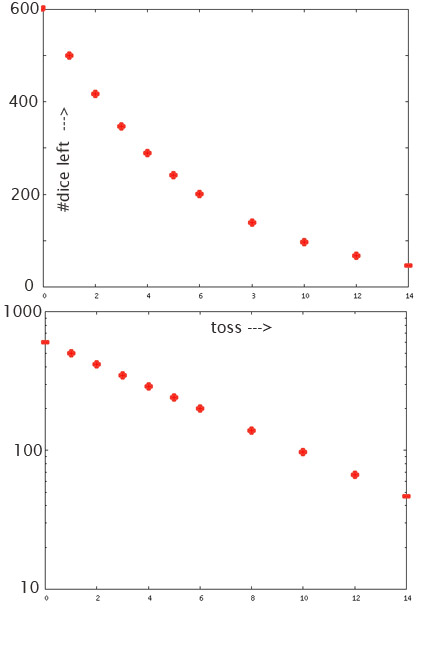

Throw 600 dice into the air all at the same time.

~ How many are likely to come down as 3?

- 1

- 5

- 10

- 50

- 100

- 500

Remove all the 3s.

Roughly 1/6 of dice come down as 3's each time. So, 100 the first time. If we remove these 100 we're left with 500. Roughly the number of dice we are left with after each throw:

| time ("throws") | $N_{dice}$ | 1/6 of $N_{dice}$ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 600 | 100 | |

| 1 | 600-100=500 | 83.3 | |

| 2 | ____ | ____ | |

| 3 | ____ | ____ | |

| 4 | ____ | ____ |

Repeat....until you get down to about 100 dice

How many dice throws to go from 600 down to 300 or less?

How many dice throws to go from 300 down to 150 or less?

Exponential decay

Exponential growth: a "J"-curve, straight on a semi-log plot, characterized by doubling time.

Dice-ish data:a "reversed J"-curve, straight on a semi-log plot, characterized by a half life.

Each dice has a characteristic probability that a "3" will be rolled in one toss: 1/6.

Each radioactive nucleus has a characteristic probability that it will decay in a second.

If the dice are tossed once per minute, what is the half-life for the number of dice: The time after which we have only half of the original number of dice?

Say you have 100 coins, and you throw them all up in the air once each minute, and then remove all the heads. What is the "half-life" for the number of coins left in minutes?

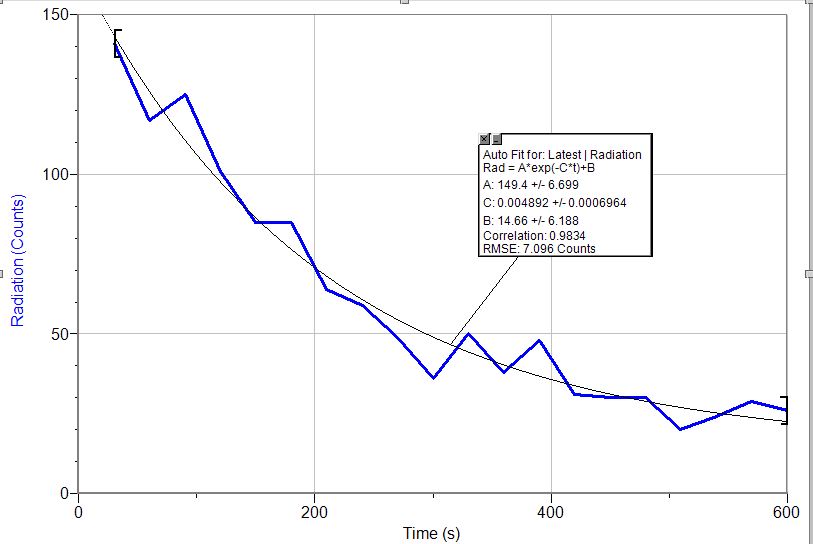

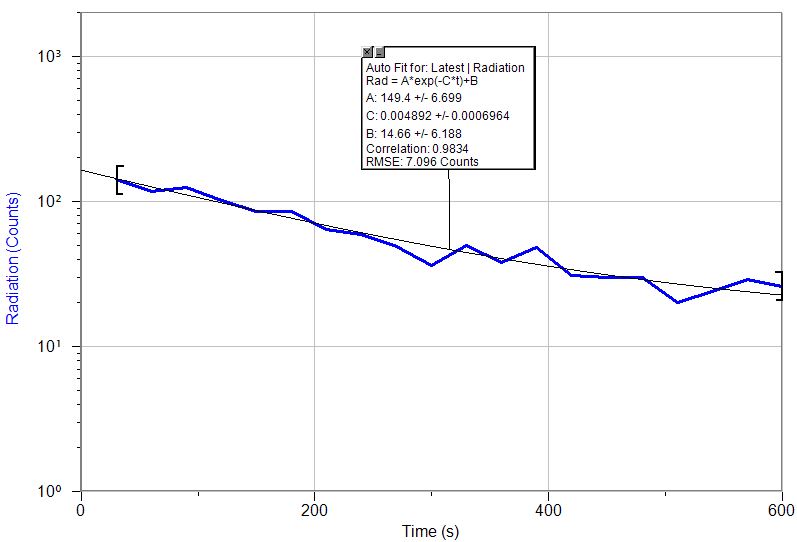

A radioactive sample

Here is data from a radioactive sample from our lab source. This is ${}^{137}$Ba:

Counts / 30 seconds, Linear $y$-scale.

Counts / 30 seconds, Log $y$-scale.

Estimate the half-life of ${}^{137}$Ba: Using the fit curve, Find the time at which there would 150 counts, and the time at which the counts would drop to 75.

The difference between those two times is the half-life=___________ s

Do the same procedure, but estimate the time to drop from 100 counts to 50 counts!

half-life estimate=__________ s

What if people died like radioactivity works?

It is worth pausing to consider how weird this is:

The current world average lifespan at birth is 67.2 years.

Let's say that we died with a half-life of 30 years:

- Half the population born in 1990 would die in 30 years--in 2020, but half of the population would still be alive. (Their age would be 30)

- 30 years later, (age 60) half of the survivors would be dead, but half (1/4 of the initial population) would still by alive.

- 30 years later, (age 90 in the year 2080) 1/8 of those born in 1990 would still be alive.

- 30 years later, (age 120) 1/16 of those born in 1990 would still be alive.

- 30 years later, (age 150! in the year 2140) 1/32 of those born in 1990 would still be alive.

Humans seem to have a pretty firm "expires by" date, but not radioactive atoms.

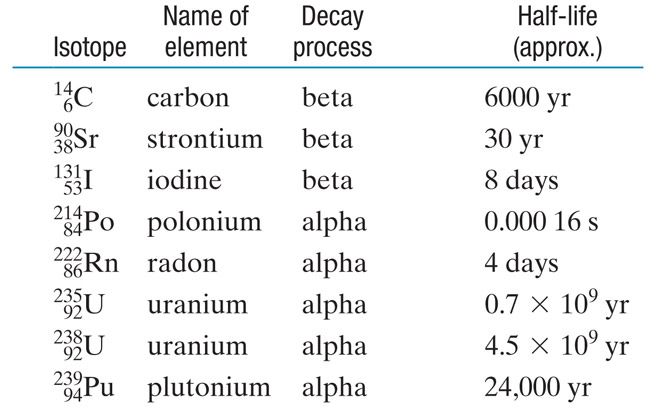

Half-lives

Carbon dating

Where do radioactive isotopes come from? We will find that many elements were made in stars.

There are 2 processes that affect ${}_6^{14}C$ in Earth's atmosphere. (Carbon in the atmosphere is mostly present in the chemical compound $CO_2$):

- ${}_6^{14}C \rightarrow {}_7^{14}N + {}_{-1}^0 \beta$

Radioactive decay with a half-life ~6000 yrs. - ${}_7^{14}N + {}_{-1}^0\beta \rightarrow {}_6^{14}C $

Extra-terrestrial particles bombard Earth, including energetic betas ($\beta$'s, or electrons).

Eventually a balance is reached where the number that decay each year is ~ equal to the number of new ${}_6^{14}C$ nuclei produced each year.

This equilibrium ratio is about

1 ${}_6^{14}C$ : 1 trillion ($10^{12}$) ${}_6^{12}C$

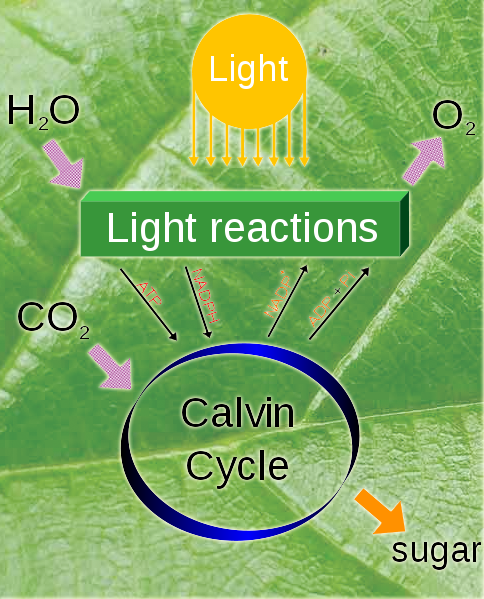

Photosynthesis

Plants inhale ${}_6^{14}C$-containing

$CO_2$ while alive, and use this carbon to store sugars, build cell walls,

etc.

While alive, their ${}_6^{14}C$:${}_6^{12}C$ ratio is... the same as the atmosphere: ~ 1:trillion.

Plant death

Death

means no new $CO_2$ coming in.

Carbon-14 decays to nitrogen, but no new ${}_6^{14}C$ is arriving.

Grind up old leaves, and count the isotopes (in a mass spectrometer)...

| ${}_6^{14}C$ : ${}_6^{12}C$ ratio | Age (years) |

|---|---|

| 1.0 : 1 trillion 0.5 : 1 trillion 0.25 : 1 trillion 0.13 : 1 trillion |

0 6,000 12,000 18,000 |

- How many years after a plant dies until its Carbon-14 : Carbon-12 ratio drops below 1% of what it was when it was alive? [instead of 1 : 1 trillion it is below 0.01 : 1 trillion.]

- Once an atom of Carbon-14 is produced in the upper atmosphere, what is the probability that it will decay sometime in the following 6000 years?

- More than 50%,

- 50%,

- Less than 50%?

- A particular atom of Carbon-14 was generated in the atmosphere 100,000 years ago, and it hasn't decayed yet to Carbon-12. In the next 6000 years, what is the probability that this atom will decay?

- More than 50%,

- 50%,

- Less than 50%?

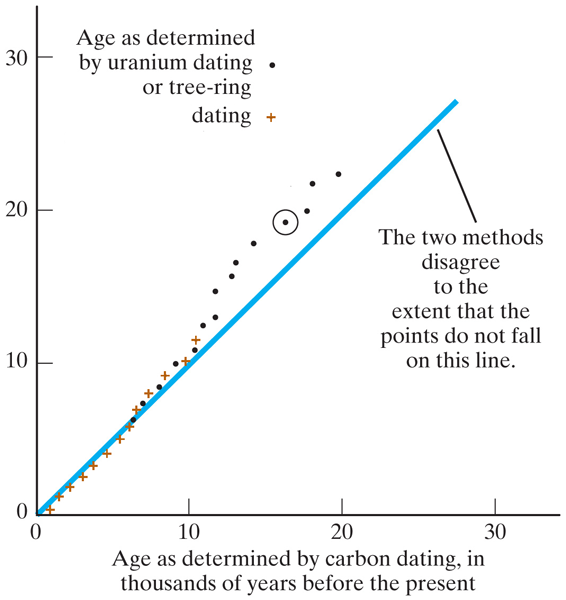

How would we know if this really works?

Check against against tree-rings: take carbon samples from different rings. Compare the ring count with the date you get from the Carbon-14 : Carbon-12 ratio.Alcohol *has to be* radioactive

The

U.S. Department of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms tests alcoholic beverages

and will not allow it to be sold unless it has "enough"

radioactivity. Why?

The

U.S. Department of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms tests alcoholic beverages

and will not allow it to be sold unless it has "enough"

radioactivity. Why?There is a law in this country that alcoholic beverages may only be made from fresh fruits, and in particular not from petroleum products.

Petroleum is the remains of plant matter, but it has been underground for 10's or 100's of millions of years: Many, many half-lives of Carbon-14 (half-life=6000 years).

$\Rightarrow$ Petroleum will have virtually no Carbon-14, and therefore no Carbon-14 decays. So looking for radiation from Carbon-14 decays is an easy way to test for petroleum vs recent fruits.

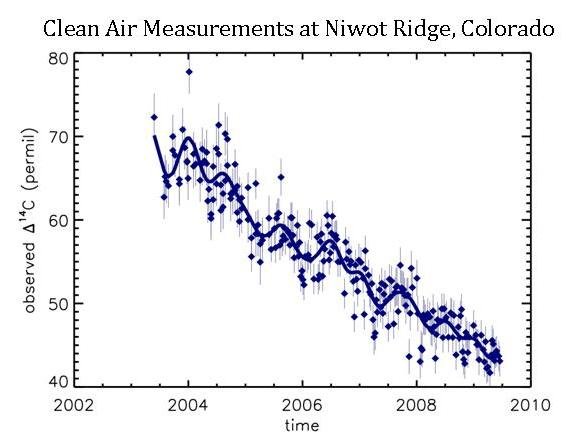

Global warming: Is CO2 due to humans?

- The Mauna Loa observatory has seen $CO_2$ levels increasing over the last few decades.

- If this is additional $CO_2$ comes from burning fossil fuels--the remains of plants that have been dead for millions of years, what should their ${}^{14}C$ content be?

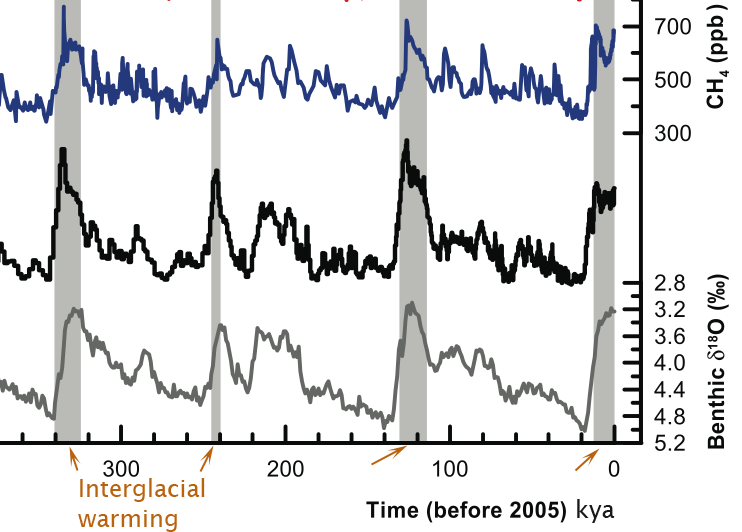

Ancient temps from ${}^{18}O$ : ${}^{16}O$

All three naturally occuring oxygen isotopes are stable: ${}^{16}O$ (99.762% natural abundance), ${}^{17}O$,${}^{18}O$. So, assume no change in terrestrial isotope ratios.

Heavy water: $H_2O$ molecules with the heavier oxygen isotopes are heavier.

Evaporation

High

temps: at extremely high temps (boiling) all water molecules

go liquid $\rightarrow$ vapor.

High

temps: at extremely high temps (boiling) all water molecules

go liquid $\rightarrow$ vapor.Low temperatures: It's more likely for thermal jostling to kick a lighter $H_2O$ from liquid $\rightarrow$ vapor than a heavier one $\Rightarrow$

- Atmosphere is enriched in oxygen-16 $\Rightarrow$oxygen-16-rich water vapor falls as snow in Greenland and forms one ice layer per year.

- Oceans are enriched in oxygen-18 $\Rightarrow$ benthic (marine life) skeletons / shells are rich in oxygen-18.

IPCC data for climate from years ago

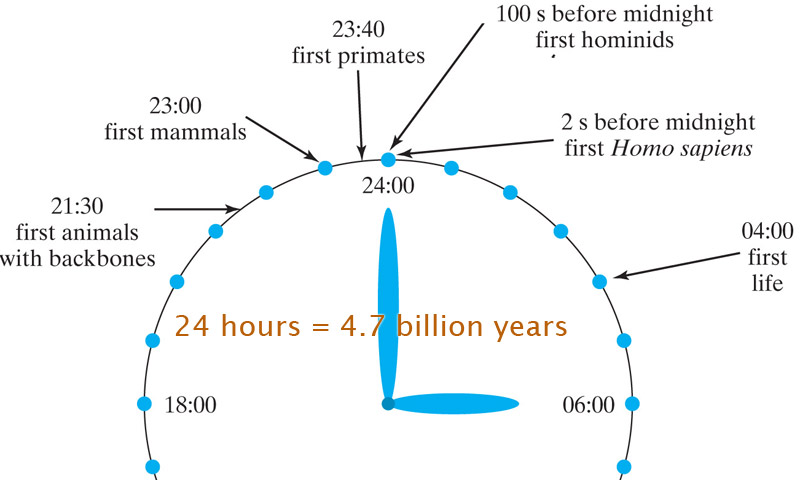

Brief history of Earth

Suggested exercises

Chapter 14, Conceptual Exercises: 17, 19, 21, 34, 35

Image credits

Oliver Kurmis, Ian Turk, Kurzon, Yzmo, Daniel Mayer, Peter Pick, water vapor, Torsten Reuschling