Mountains and Valleys

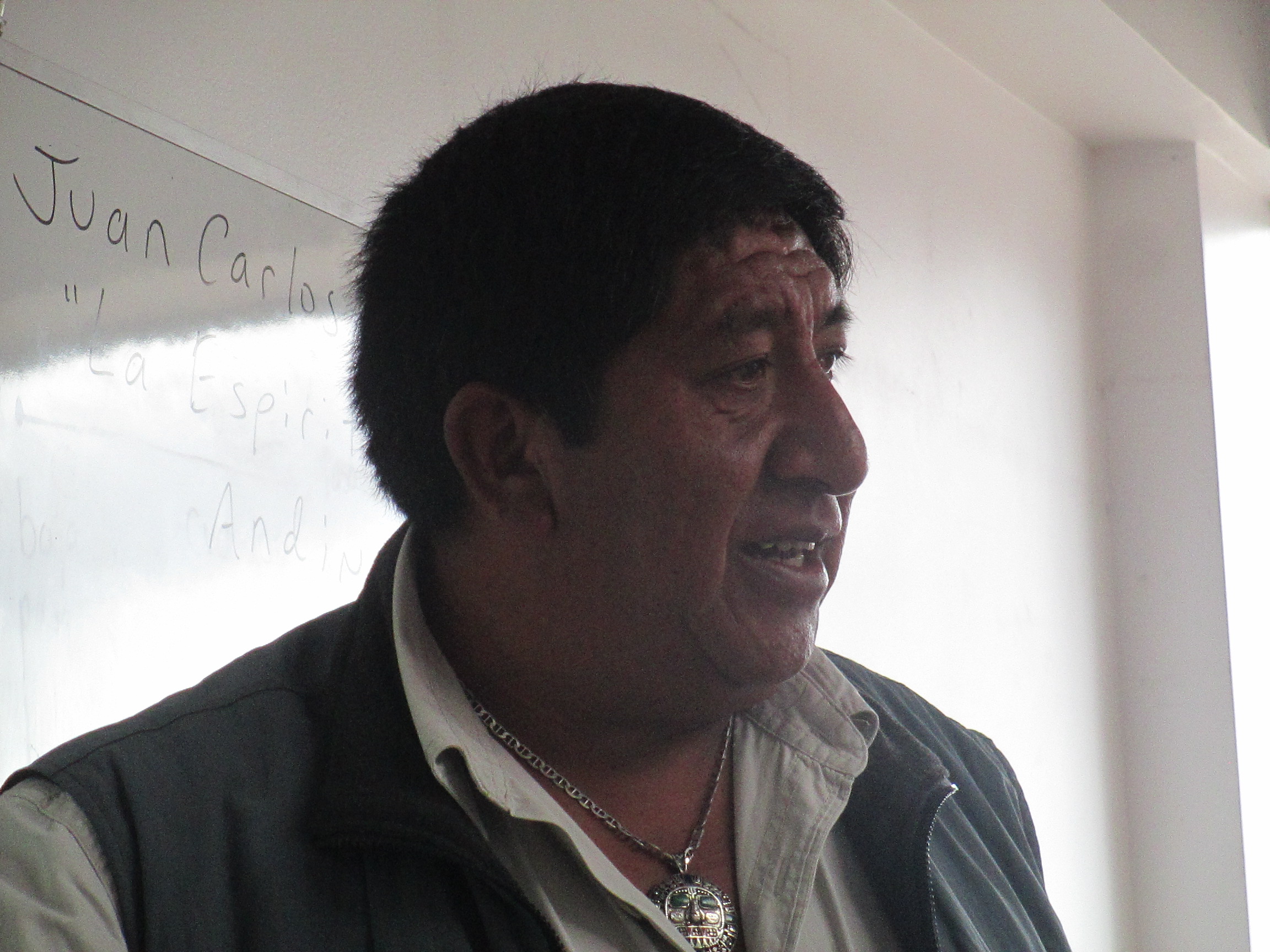

The Andes are a fascinating place, steeped in history and buzzing with activity. It is commonly held that the Inca people believed in a variety of dieties, including the sun, the stars and the snow-capped mountains. But one of our speakers, Juan Carlos Machicado, has a different perspective on Andean spirituality. His studies of Spanish manuscripts and Inca archaeology, along with visits to distant communities where the old ways are still practiced, lead him to the conclusion that the Incas as well as many cultures that preceded them believed in a creator God named Wiracocha who, along with Pachamama (mother earth), created and continue to sustain life on this planet. In other words, Machicado contends that the Andean people were monotheistic. The Spanish explorers, or conquistadores, either failed to recognize this or found it more useful to portray the Andean people as pantheistic savages who needed to be “civilized”. Ironically, the Inca society that the Spanish encountered when they arrived here in 1532 was remarkably sophisticated and the cities the Spanish plundered were more developed than any in Spain at that time.

Catalina Jimenez, an agronomist at the National University of San Antonio de Abad in Cusco, described the 21st century impacts of mining on the Peruvian landscape. Mining is the main driver of the Peruvian economy, a source of dollars, euros, yen and countless other currencies in exchange for the gold, silver, copper, lead, tin and other minerals that are readily found in these mountains. Unfortunately, virtually all of the minerals are shipped out of Peru as raw materials — there is very little manufacturing and the earnings from mining are used to purchase electronics and other consumer products that are made from the very materials that were exported. Mining also causes air, water and soil contamination that destroys the environment and impacts human health. And the social consequences can be devastating as well. Miners typically relocate to hastily-constructed camps near the pits for 20-25 days at a time. Without the presence of their spouses and families, they quickly spend much of the wages they earn on alcohol, prostitutes and illegal drugs. This phenomenon has led to high incidences of alcoholism, drug addiction and sexually-transmitted diseases among both miners and the Andean people who live near them. Professor Jimenez called for better programs to deal with these problems and invited the students to return to Peru some day in order to lend their expertise and help promote a more sustainable future.

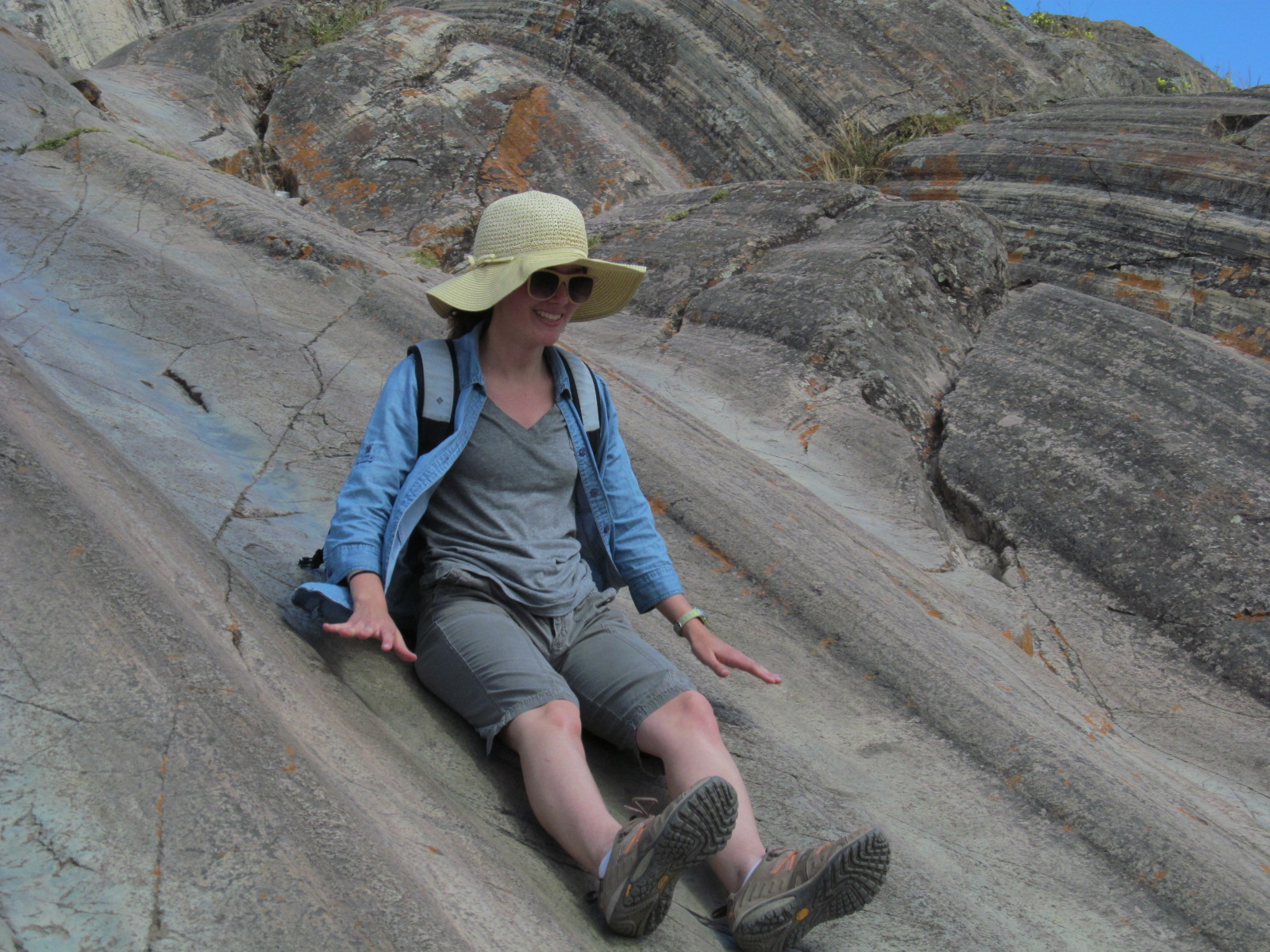

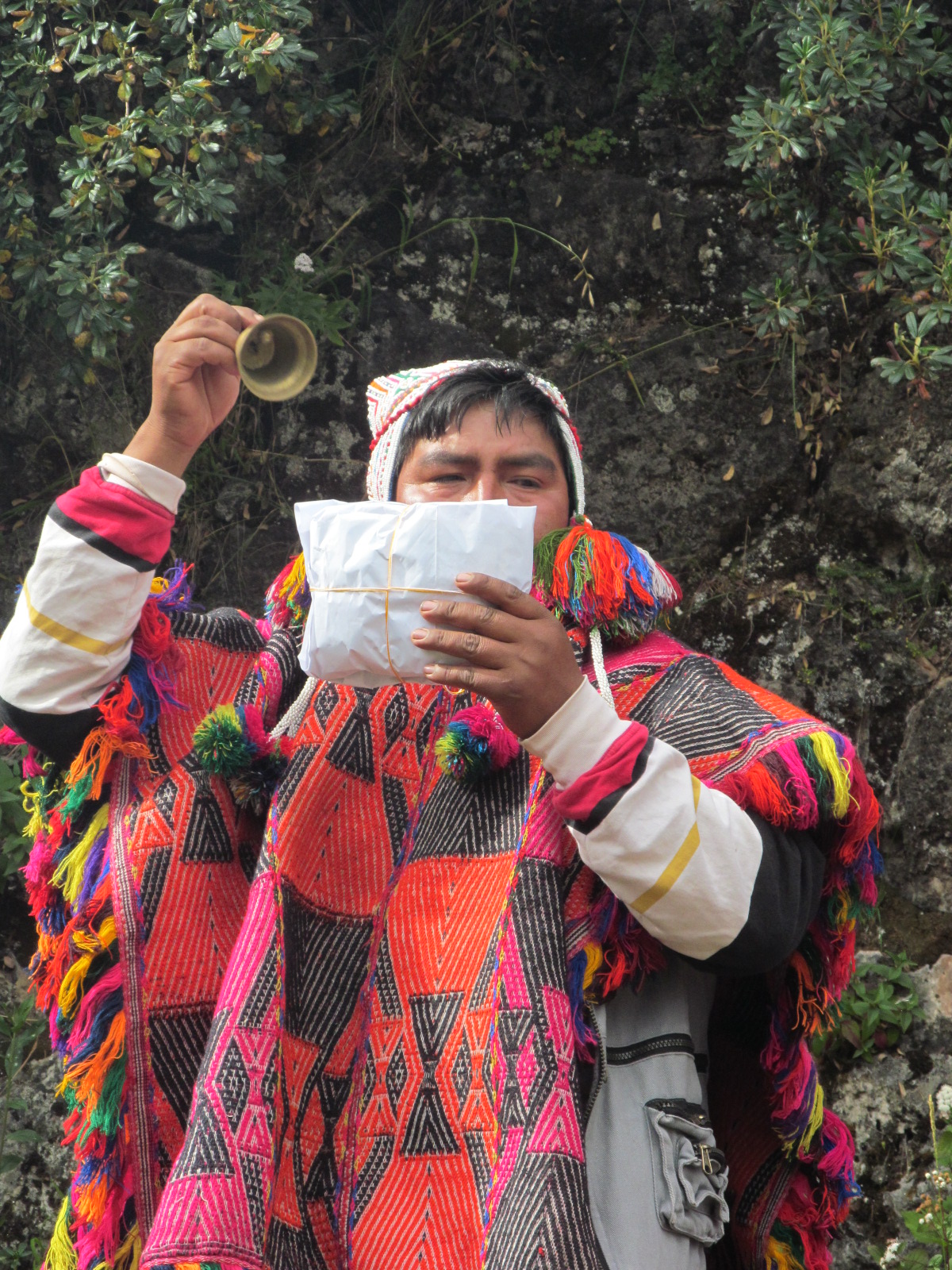

Sacsayhuaman is an epic archaeological complex situated above the city of Cusco. Once considered a “temple of fertility” (Sacsa Uma in Quechua), the name was changed after a bloody battle between Spanish solders and Inca warriors. Sacsayhuaman means “satisfied falcon.” Our guide, Oswaldo Palomino, described how birds from the surrounding area flocked here due to the presence of so many corpses on the battlefield. Today the place is a marvel to behold — huge stones, tightly fitted together, form the shape of a lightning bolt. After touring the main site the group was led past the Temple of the Moon to a grassy area where the students enjoyed a picnic lunch before beginning a 10-kilometer hike back to town. Along the way they witnessed a ceremony performed by a curandero, or shaman, who offered his payment to Pachamama (mother earth), a practice that continues today.

The end of the week brought the conclusion of our program of lectures, workshops and Spanish classes in the Andes. The students’ instructors and host families were invited to a clausura (farewell celebration) featuring thank you’s, a slide show, music, singing and refreshments. The students returned home with their families and enjoyed their last weekend together before embarking on a five-day tour of the Sacred Valley.