Conquest

Peru has a long history of conquest. The Incas were known for subduing neighboring peoples with generous gifts and military might, especially during the reign of its greatest leader, Pachacutec. By the beginning of the 16th century, the Inca realm covered all of modern day Peru, as well as parts of Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina. Soon thereafter came the Spanish, who were motivated by two factors: a lust for riches and a desire to evangelize. From 1532 until 1821, the Spanish colonists shipped countless tons of gold and silver back to Europe and converted most of the population to Catholicism. But the devastation left in their wake was unimaginable. Over this same period Peru’s population dropped from 12 million to only half a million; most of the Andean population fell victim to disease, violence and maltreatment by their Spanish overlords.

In 1821 Peru gained independence. But troubling inequality persisted, with wealthy families in Lima and other coastal cities holding most of the nation’s wealth and dominating its politics. In the second half of the 20th century a university professor heavily influenced by Maoist philosophy, Abimael Guzmán, started a movement in the highlands to help the poor by replacing the country’s leadership with his own. The Shining Path was motivated by communist ideology and a desire to redistribute the nation’s wealth from the haves to the have-nots. But his methods were as bloody as the Spanish. From the mid-seventies to the mid-nineties at least 69,000 people were killed in the conflict — half at the hands of the terrorists and half at the hands of the government soldiers charged with eradicating terrorism. Countless more were injured, raped, tortured and removed from their communities as they fled the violence. The nation still suffers from what might be termed a collective case of PTSD: Post-traumatic Stress Disorder.

The conquest of one people by another is often justified for religious and ideological reasons. But economics often plays a role as well. Today some observers view the increasing influence of multinational corporations in Peru’s economy as a new kind of colonialism. Globalization has brought well-known brand names — Coca Cola, Levis, McDonald’s, Starbucks — to metropolitan Lima. These and other products are marketed to up-and-coming Limeños in billboards, print advertisements, television commercials and product placements in movies. Having more choices in what to drink, what to wear and what to eat are, at first glance, a good thing. But critics note that the rise of a North American fast-food chain restaurant in a particular neighborhood often brings a decline in the number of local eateries. Economic domination by well-financed multinationals may eventually lead to a homogenization of culture rather than a manifestation of diversity.

Globalization is new to this part of the world and Lima still offers a wide range of options to its residents, reflecting the diversity of the people that populate Peru’s coast, its highlands and its rain forest. Consumers continue to have choices and the decisions they make will have a lasting impact. When young professionals decide where to eat lunch, for example, they are not only deciding what to feed themselves. They are also deciding which business they will feed with their nuevos soles, the local currency. If KFC’s advertising (known as “propaganda” in Spanish) steers people into one of its restaurants — there are now 50 in Lima — then this well-known chain featuring Kentucky fried chicken will prosper and grow. If, on the other hand, people walk into a local establishment and order pollo a la brasa (rotisserie chicken), this Peruvian specialty and the establishments that prepare it will thrive. In the end, which businesses grow and which disappear depends largely on the choices made by Lima’s public and, increasingly, the foreign visitors (like SST students) who spend their money here.

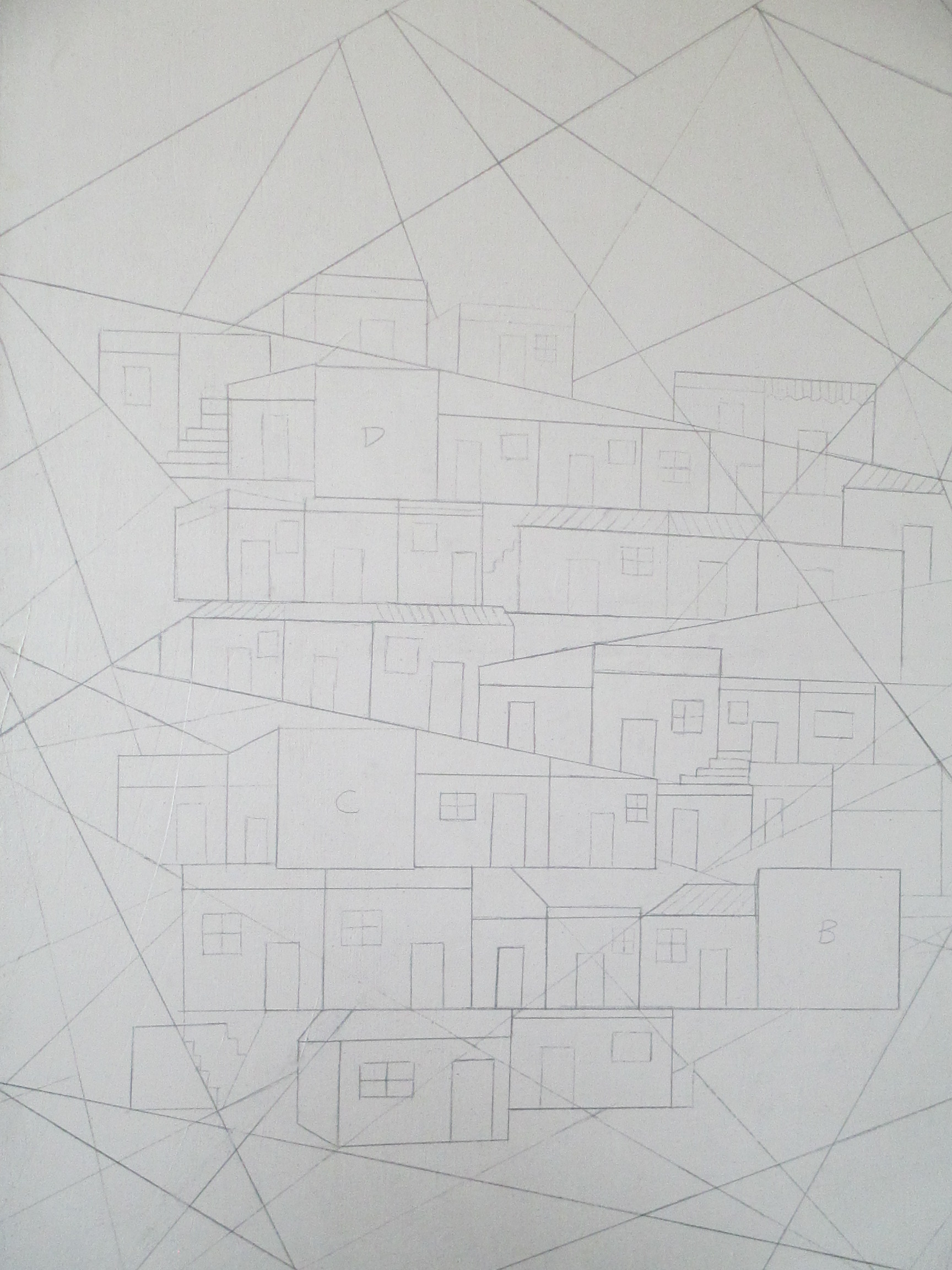

As we ended our study time in Lima, we traveled downtown to tour a Catholic monastery and see the stately buildings constructed by the Spanish during the colonial period in what they called the Plaza de Armas (literally, “Plaza of Weapons” or, figuratively, Parade Grounds). The nation’s traditional power structure is evident when standing on the Plaza: to one side is the Catholic Basilica, to another is the Presidential Palace, to a third is the Municipal Government Building and to a fourth is a commercial center featuring a large pedestrian mall that begins across the street.

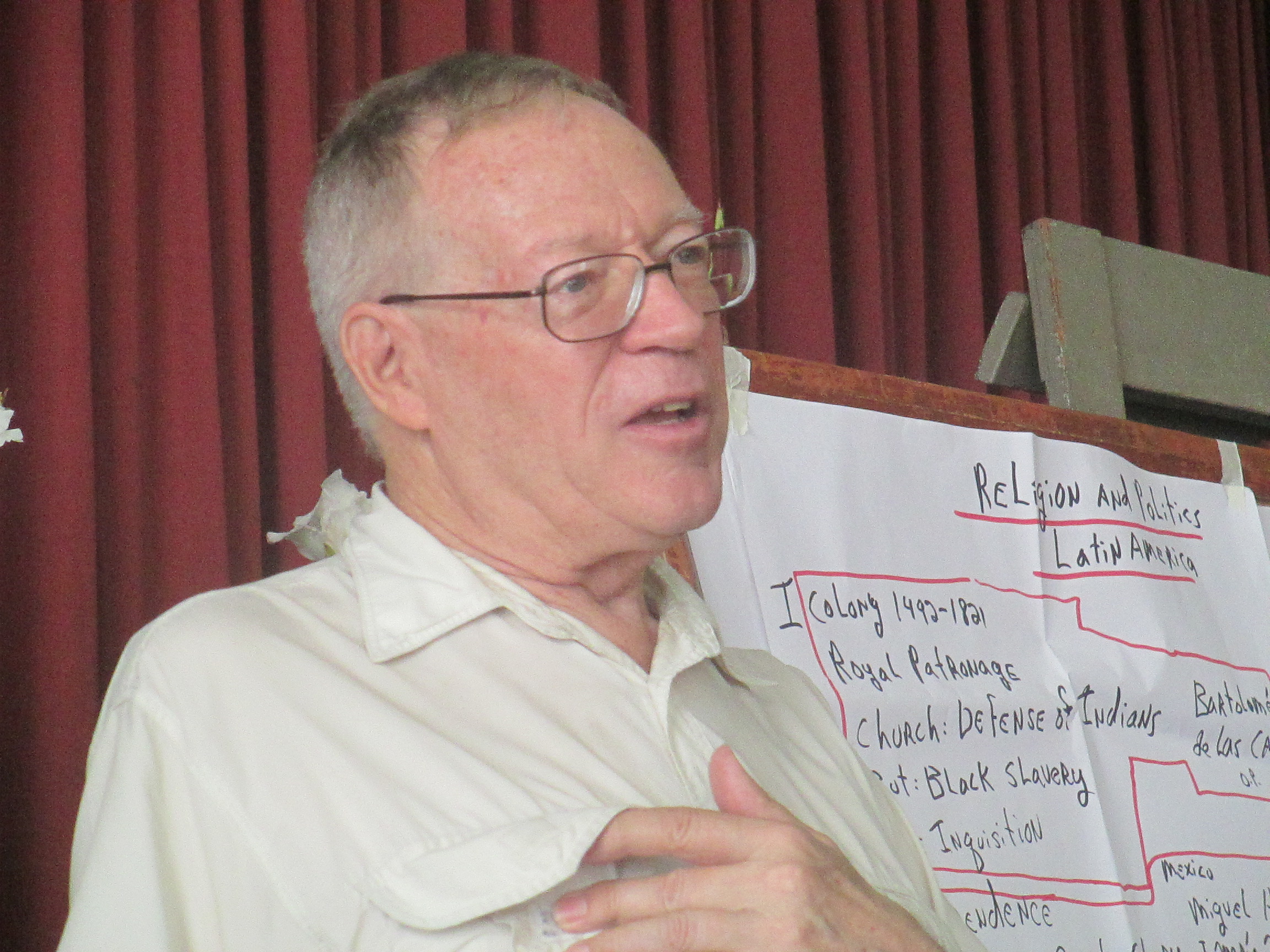

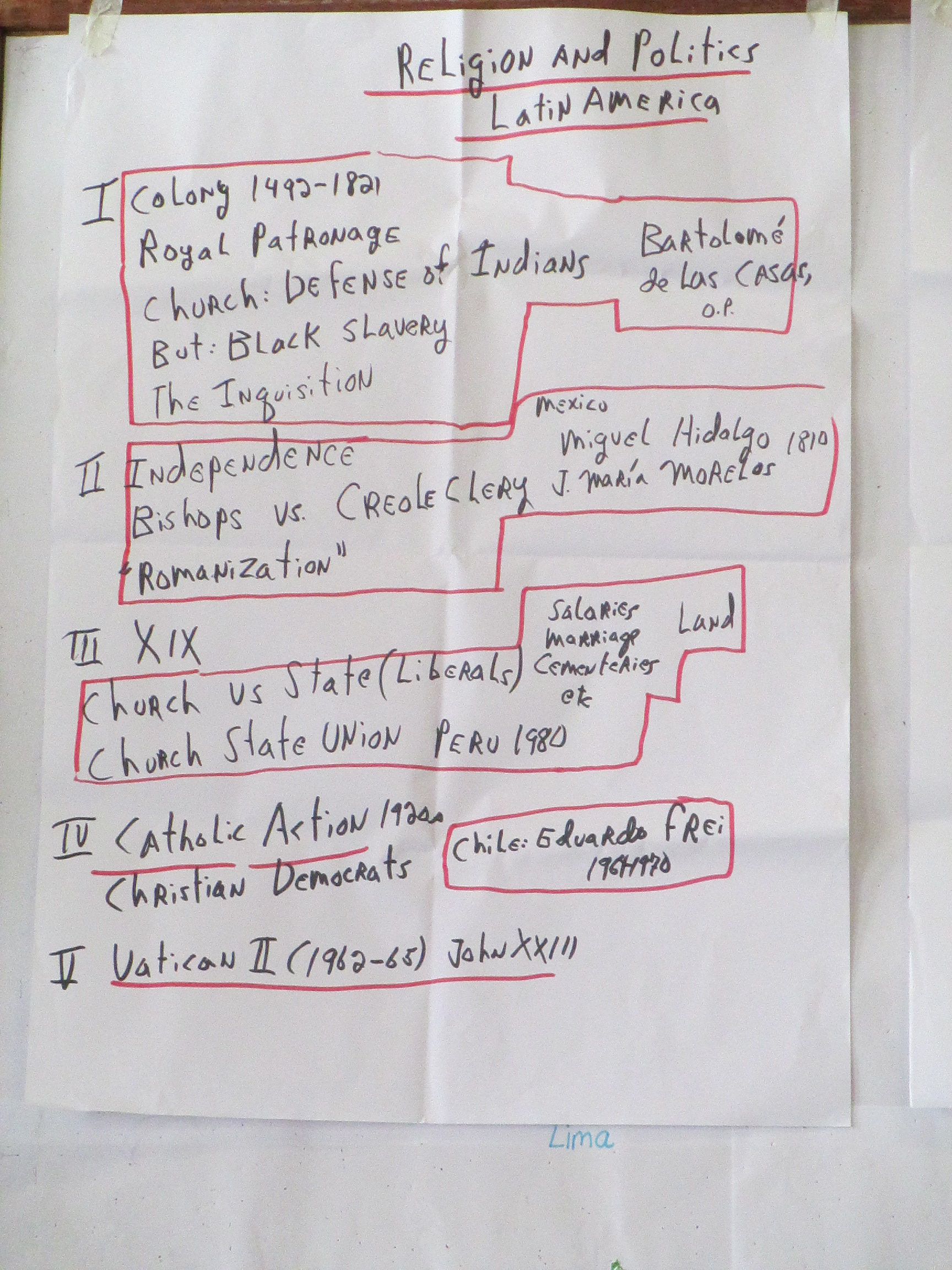

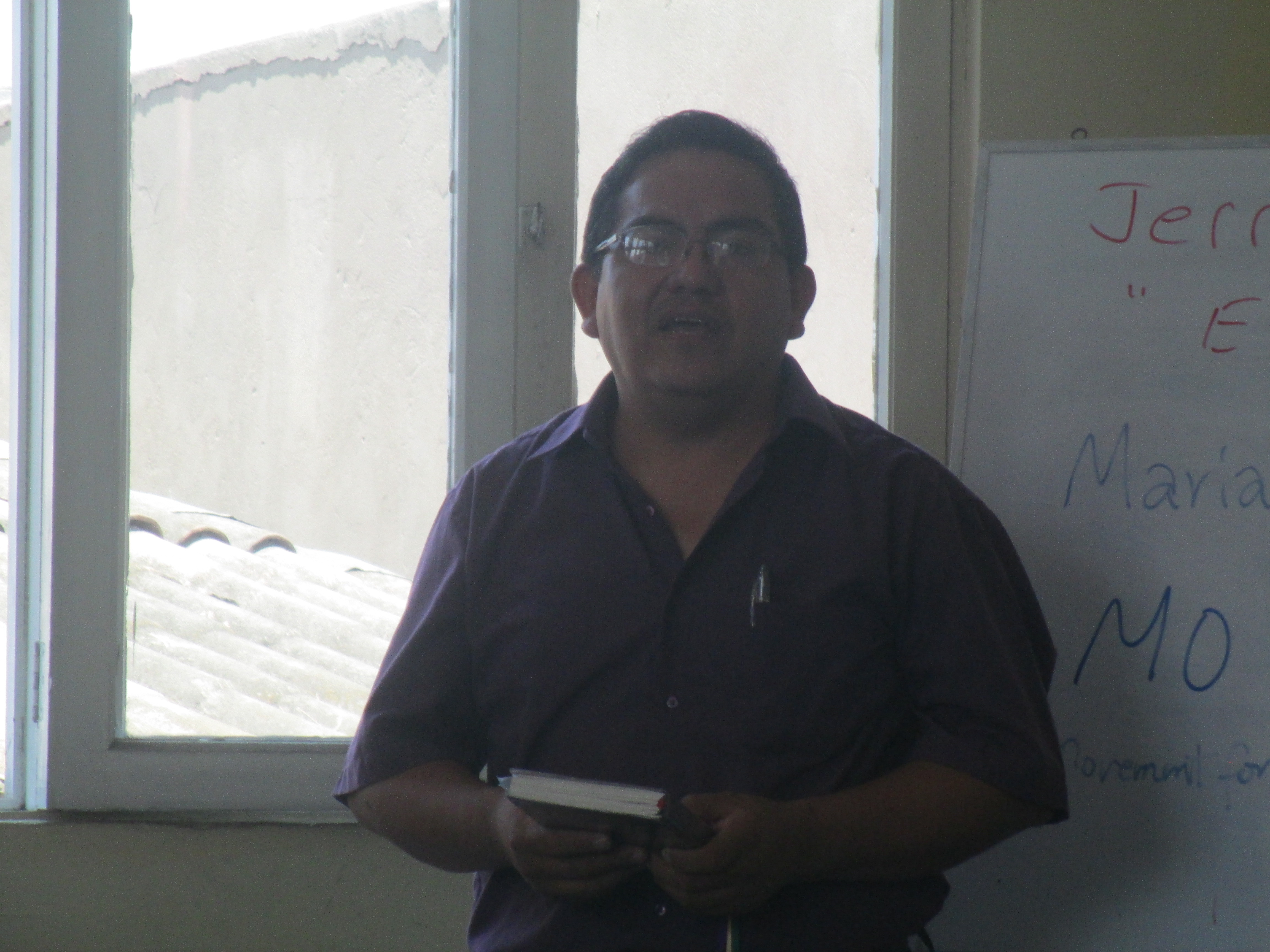

We also learned about power and domination, for better or worse, from listening to Jerry Acosta’s account of what life was like during the time of terrorism. His description of the Shining Path’s methods — assassinations, bombings and public executions — was difficult to listen to and left a profound impression on each of us; how cruel humans can be when they demonize their enemies. Another speaker, Father Jeff Klaiber, described the role of the Catholic Church in Latin American politics, with particular focus on the recent resignation of Pope Benedict XVI and power struggles between Peru’s largely conservative bishops and its more liberal priests.

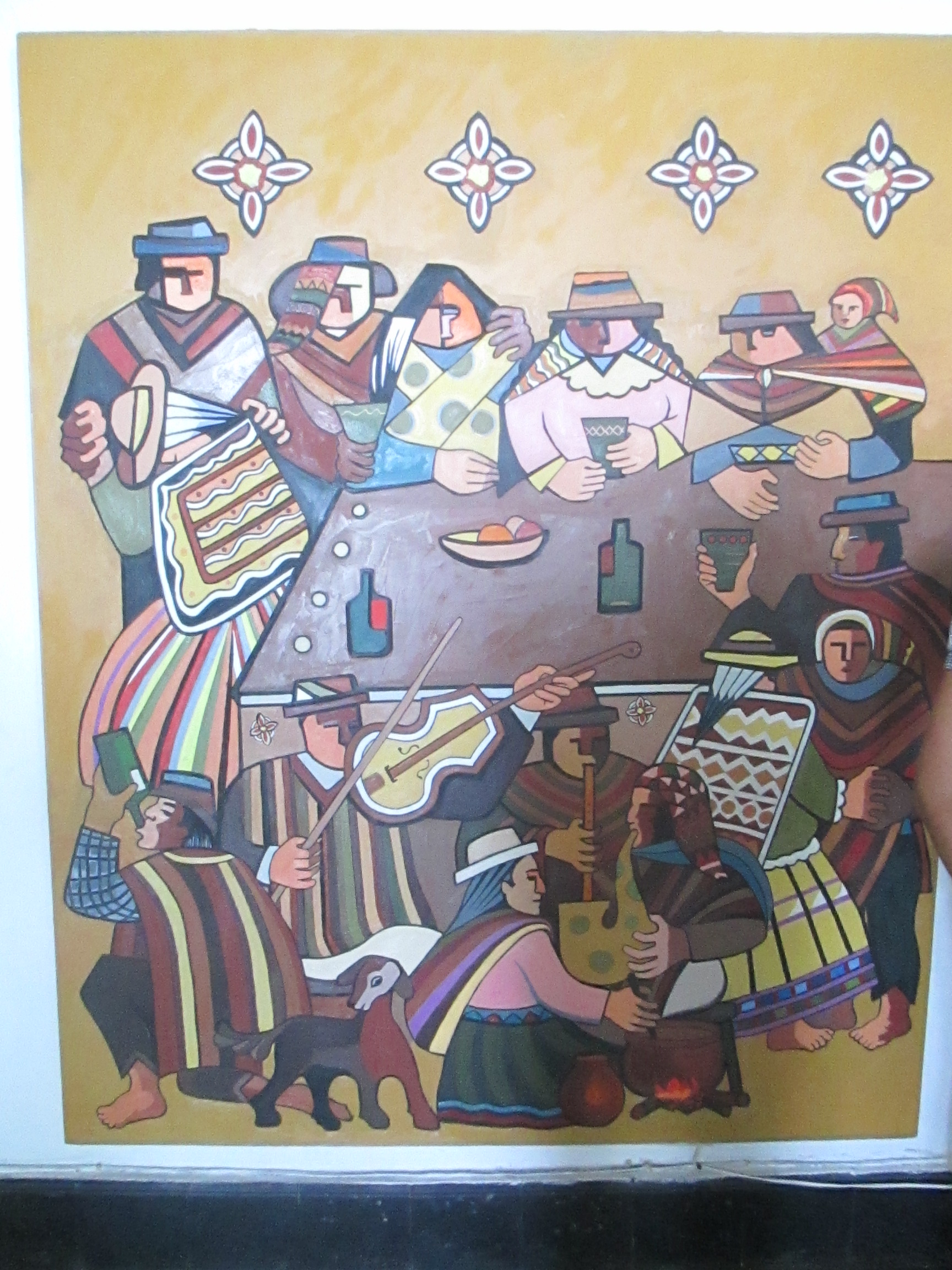

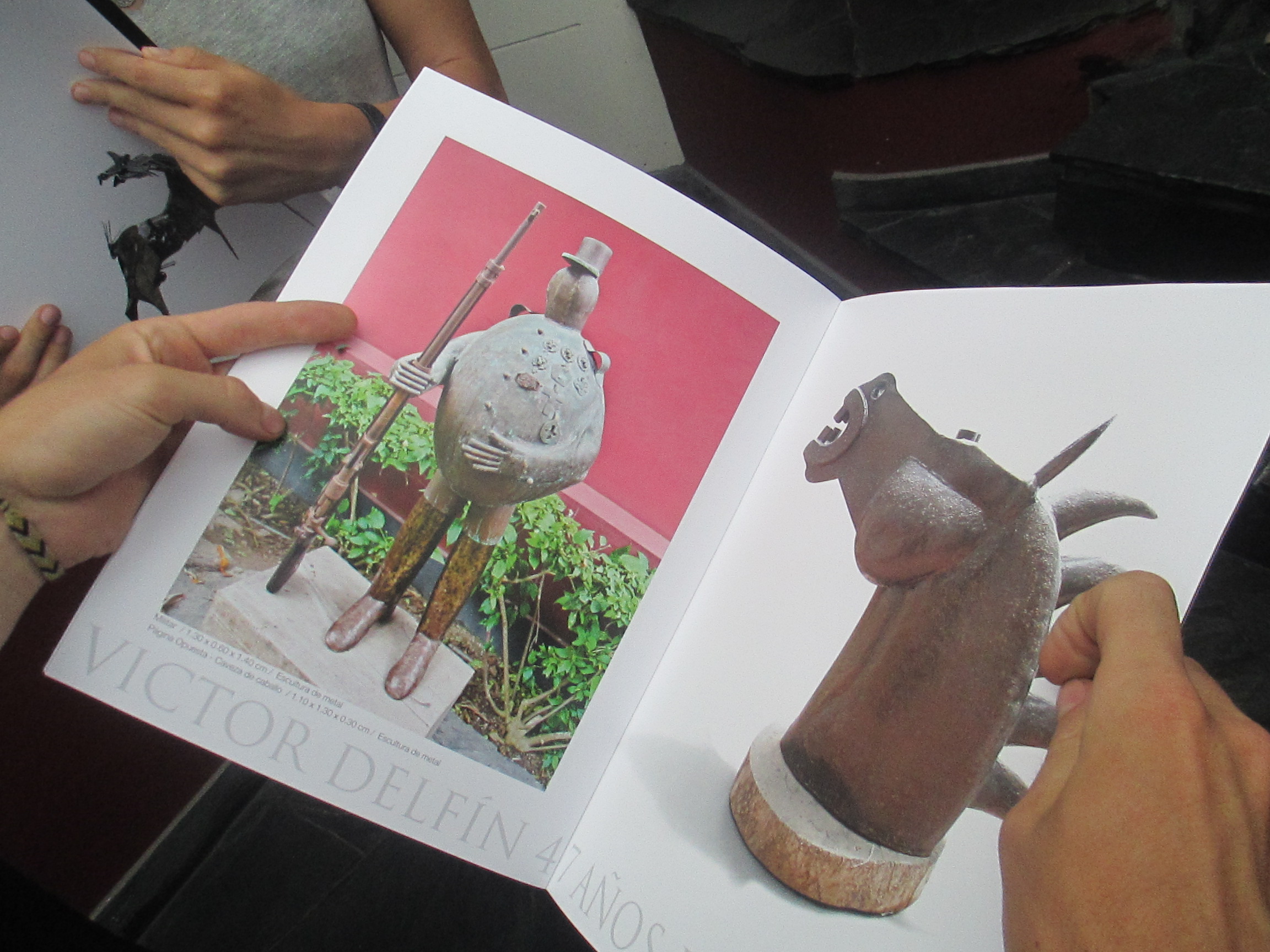

For our last study activity of the term we traveled to neighboring Barranco to visit the gallery and studio of Victor Delfin. Themes of power and conquest dominate the work of Peru’s best-known artist. Mr. Delfin is extremely talented and amazingly adept at expressing himself in a wide variety of media — oil paintings, wood carvings and sculptures in steel and bronze, to name a few. Our tour of his gallery and conversation with the artist helped deepen our understanding of life for a people that is heavily influenced by forces outside its control but is nonetheless seeking to protect and promote its own unique customs and distinctive culture. Viva Peru!