Out of the classroom, into the world

Why international, experiential learning is so pedagogically powerful

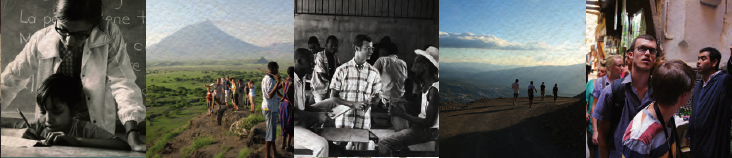

Study-Service Term: 50 years of transformational global citizenship

By Keith Graber Miller

In his opening remarks at a service-learning conference a quarter century ago, Goshen College president emeritus J. Lawrence Burkholder said he claimed only one credential for speaking at the event: He was a “born again” believer in international education.

As one who has co-led nine Study-Service Term (SST) units — in Dominican Republic, Costa Rica, Cuba, China, and Cambodia — I write today as one similarly reborn. And in the spirit of some Dominican evangelicals, I’ll testify to a series of rebirths during my years of teaching in a small, Mennonite, liberal arts college — recommitments to graceful living as well as to international education, and to service or experiential learning. God knows, I’m a believer.

In my undergraduate years at a college with no international educational program, I intuitively recognized the need for and value of cross-culture education and experiential learning. In my sophomore year, a friend and I spent six weeks of the Christmas break and January interterm backpacking and train-hopping our way through Western Europe, communicating in our halting French and German and smiling and gesturing profusely when we traversed Italy and Spain. Revelatory experiences came each day, and I reflected on those experiences in a journal that expanded to four volumes by the end of the six weeks.

Many years later, I want to highlight why experiential or service learning — in international settings as well as on our campuses — is essential, and why it may be effective.

1. Experiential learning is one of our earliest modes of development.

1. Experiential learning is one of our earliest modes of development.

Our initial insights come not in reading or rote memorization or academic discourse. As infants we gradually discover parts of our body we never knew existed, one day finding our feet and then inserting them into our mouths to see what form and texture and taste they have. We learn that dropping liquids on the floor results in a flurry of activity, recognizing the realities of cause and effect. During our earliest months of life, experiential learning is woven into our being. It is how we first come to know ourselves and our worlds, and the value of such learning sticks with us.

2. Experiential learning takes us into the realm of the unfamiliar.

2. Experiential learning takes us into the realm of the unfamiliar.

With infants, everything is new. With college-age students in international education programs, or their crustier faculty leaders, much is new. And for most of us, newness engages us, draws us out, stimulates us, makes us open and vulnerable, teachable.

For our SSTers in the Dominican Republic (D.R.), the realm of the unfamiliar came perhaps even more so in Haiti than in our primary host country. Our students came to the D.R. aware of what the country and its people would be like because of their orientation at GC and the SST culture on campus. But they were unprepared for our four-day excursion to Haiti, where we switched to a language none of us knew, and where we heard about development from Haitians and others whose perspectives we had never encountered before, and where we lived with former street boys who had undergone religious and quality of life changes about which we had been clueless.

3. Experiential learning requires us to think carefully and critically about and from other perspectives.

3. Experiential learning requires us to think carefully and critically about and from other perspectives.

Faculty members who have led international education programs usually have multiple, glorious stories of “aha” moments or revelatory breakthroughs in critical thinking. I want to mention a more mundane one, though its impact was far-reaching. In the D.R., most of the students’ transportation takes place in carros publicos, usually beaten up, taped together (literally), decade-old Toyotas which scuttle down Santo Domingo’s primary streets, picking up anyone wagging the Dominican finger. In these ancient and tiny wrecks, it’s expected that two people sit in the one front bucket seat and that four people crowd into the back.

Several weeks into the summer term, some of our students were remarking about the insanity of a common occurrence. They briefly would be alone in a publico with the driver, sitting comfortably in the front bucket seat, when another passenger-to-be would finger the car to a halt. Then, even though the backseat was empty, the new rider would open the front door and pile, nearly onto the lap, of our student. The assumption of some of our SSTers was that this was, at best, an attempt at undesired physical intimacy or, at worst, a sign of Dominican senselessness.

As we discussed this at “Casa Goshen,” the weekly group-processing time in our home, we realized that because of traffic patterns and the dangers of exiting and entering cars, all passengers were required to exit publicos from the right doors rather than into the roadway.

That meant the person who sat on our students’ lap would have inconvenienced the publico’s future passengers had he entered the back seat of the car, where he would have been eventually pressed against the driver’s side door. For him to exit the car, especially if he were going a short distance, all of the other passengers who by then would have filled the back seat would have needed to get out before he could exit. His act, then, in scrunching into the front seat, was sensitive, appropriate and eminently rational.

The student who brought the incident to the group was bowled over. What had been senselessness had been transformed through seeing from another unconsidered perspective, and the chastening that came through the revelation carried over into the remainder of her experience.

4. Experiential learning breathes life into our study, makes our learning both practical and real.

4. Experiential learning breathes life into our study, makes our learning both practical and real.

Even near our home campuses, in practicums and internships and student-teaching assignments, engaged experience helps students make practical applications of their earlier learning, and they return to the classroom sharper and more mature in their thinking, and more engaged in their study.

In the Dominican Republic, we altered the curriculum for our summer SSTers, partly by adding in a major block on women’s issues, building on the powerful story of the Hermanas Mirabal, three sisters who were assassinated by the dictator Trujillo in 1960 for participating in a resistance movement.

In addition to our lectures on domestic violence, prostitution and women’s roles in the culture, we read Julia Alvarez’s historical novel In the Time of the Butterflies, which chronicles the lives and deaths of the Mirabal sisters. We also were able to arrange a meeting with Dede Mirabal, the surviving sister. Dede responded to our questions for 45 minutes, showed us through her house and gardens, and signed our novels. Students were deeply moved, and the history of the Mirabals as well as the Trujillo regime came alive for them in the person of Dede. Such experiences can’t be replicated in the classroom.

5. There is theological warrant for international education and experiential learning.

5. There is theological warrant for international education and experiential learning.

Here I quote one who has reflected with depth on experiential learning, largely through the lens of Goshen’s SST program. Former program director Wilbur Birky once wrote a piece titled “SST: Vision, History and Ethos,” in which he draws on the biblical metaphor of the incarnation.

“Let us propose the Incarnation as an act of divine imagination rooted in a profound realization that even God could not know and understand the human condition completely without entering into it, to experience it in the body. That was a true cross-cultural experience. So a description of at least the early parts of Jesus’ incarnation applies aptly to the SST experience: it is to give up one’s customary place of comfort, to become as a child to learn a new language and to eat in new ways, to be received into a new family, to attend the local house of worship, to question and be questioned, to experience frustration and success, and to learn to serve in the very thick of life.”

In the Christian tradition, the incarnation is understood to be a form of crossing over, an experience in humbling, and an identification with others. Such is the nature of much international education.

I’m a believer.

My hope is that I never forget how needful I am, how needful we all are, of passions and experiences outside the classroom — internships in schools if we teach education; time in churches or with social-service agencies if we teach Bible and religion; blocks of time in the business world if we teach in that department; the occasional international education experience to reinvigorate our sensibilities. As teachers, we need ongoing experiential learning if we are to have anything to teach. And with such learning, we also will be able to better value such a pedagogy.

Experiential learning in international settings — for teachers as well as students — renews, restores, matures, provokes, transforms, and educates — toward excellence and toward wholeness. I’m a believer.

Keith Graber Miller is professor of Bible, religion and philosophy. The full version of this article was originally published on The SST Stories Project and can be read at goshen.edu/sst/50.

Celebrate SST’s anniversary online and share your story

Visit the new SST 50th anniversary website (goshen.edu/sst/50). It includes access to the SST Stories Project, SST videos, a list of SST-related publications over the years, links to unit blogs, a listing of SST-related events this year and more. More content will be added during the year.

Share your SST story and favorite photo:

- Do you have an SST story you would like to share? Submit it through the website.

- Do you have a favorite SST photo you would like to submit with a story caption? You can also do this on the website.