Martin Luther King Jr.’s visit to Goshen College in 1960 inspired the entire campus

By Richard R. Aguirre

Many famous people have visited Goshen College since it was founded in 1894 — none more famous than the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

The slain civil right leader visited Goshen College on March 10, 1960. At the time, King was leading the struggle for racial equality throughout the South.

The charismatic pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Ga., soared to national prominence in 1954 by leading a boycott against the segregated bus system in Montgomery. Ala. He had endured many threats to his life and had been arrested in protests. A year before his Goshen visit, in 1959, King spent a month in India studying Mahatma Gandhi’s techniques of nonviolence.

In later years would come more protests, more arrests, the March on Washington, the “I Have a Dream” speech, the Nobel Peace Prize — more triumphs and more frustrations.

But on the evening of March 10, 1960, King delivered a spellbinding lecture to a crowd packed into Goshen College’s Union Auditorium, according to news accounts.

The Elkhart Truth and the South Bend Tribune reported that King lectured about the “sit-down” strikes against segregated restaurants that already had spread to 37 cities in the South. “The strikes will arouse the dozing conscience of the South,” he predicted.

King condemned police tactics used against student demonstrators and he spoke about his commitment to non-violence. King told the crowd about a telegram he had just sent pleading for President Dwight D. Eisenhower to help end the “reign of terror” by police against the students in Montgomery, Ala.

King described the “Negro’s quest for freedom,” the Tribune reported, and stated that the nation faced a moral challenge.

“We have broken loose from the Egypt of slavery. We moved through the wilderness of segregation. We stand now on the border of the promised land of integration,” the Tribune quoted King as saying.

“All over the South, the Negro is rising up and saying he is determined to be free, he is tired of the yoke of oppression.”

The Truth reported that King called on Congress to pass a strong civil rights law to “control the effects” of racist attitudes. “Law cannot make a man love me, but it can keep him from lynching me,” he said.

King also called on religious leaders to help change attitudes on racial issues. He pointedly noted that churches were a “segregated island” in America and he said that political moderates and liberals had an obligation to speak out in protest.

“What is needed now is a liberalism committed to the ideals of brotherhood,” the Tribune reported. “White moderates in the South must take a stand.”

King also said that all persons should be free to marry whomever they wanted, but he rejected the idea that a desire for intermarriage had any bearing on the drive for civil rights, according to The Truth’s story. “The basic aim of the Negro is to be the white man’s brother, not his brother-in-law,” he said.

In her book, “Culture for Service, A History of Goshen College,” author Susan Fisher Miller (a 1980 Goshen College graduate) wrote that King’s visit “sparked a great deal of interest” on campus and spurred sustained activism against segregation.

Still, the story behind the visit is almost as fascinating as the positive reaction it provoked on campus and in the community on March 10, 1960. This story also provides a glimpse at the racial tensions sweeping the nation at the time and about the college’s strong support for King at a time many Hoosiers opposed or were skeptical of King’s efforts.

Getting King on campus

This little-known story can be told based on records of the Goshen College Lecture-Music Series — specifically the correspondence between Professor Willard H. Smith and Martin Luther King Jr. — that are housed in the Mennonite Church USA Archives at Goshen College. Dennis Stoesz, the church’s archivist in Goshen, shared the records.

The records show that Professor Smith, the chairman of the lecture-music series, wrote to King on Feb. 5, 1959 and invited him to lecture at the college in January 1960. After a few months of correspondence, King wrote a letter in which he thanked Smith for the invitation, but politely declined.

“Ordinarily, I would be more than happy to accept your invitation,” King replied in a letter dated April 8, 1959. “Unfortunately, however, some road blocks stand before me at this time. Because of the mounting racial tensions in the South, I find it necessary to spend more of my time in this area.

“This means keeping my outside engagements to a bare minimum. After checking my calendar, I find that I have accepted as many speaking engagements outside the South as my schedule will possibly allow for the next year. But for this, I would be glad to accept your gracious invitation. Please know that I deeply regret my inability to come at this time,” King wrote.

Despite the rejection, Smith persisted. He called King and proposed alternative dates for a lecture. A few days later, on April 11, King wrote a letter in which he indicated that he might be able to lecture at Goshen College after all. He proposed a visit on Feb. 19, 1960.

In the letter, King declined to specify what his speaking fee would be but he urged the college to be generous. He wrote Smith: “… I do urge the sponsoring group to make the honorarium as high as possible since the bulk of it goes for my work here in the South. Let me thank you again for extending the invitation and I look forward with great anticipation to the time when I will appear at Goshen College.”

Professor Smith called and told King’s aides on April 14 that a lecture on Feb. 19, 1960 was impossible for the college. Smith proposed three alternate dates in January 1960, and he stated that the college would pay King a “good fee” if he agreed to the visit. Smith further requested that King respond on April 15, according to archive records.

On April 15, 1959, Smith received a Western Union telegram that must have been received with great joy at the college. Its entire text: “Have arranged to speak at Goshen on January fourteenth. Martin Luther King Jr.”

On April 28, following more contacts, King sent a more formal response. He agreed to speak at the college for a $600 fee. “I am placing January 14, 1960 on my calendar, and I look forward to this engagement with great anticipation,” King wrote.

For months afterward, the college worked with King and his secretary to finalize details of the lecture, according to the archive records. Advance publicity was arranged after King’s office sent the college “glossy” photographs and biographical material.

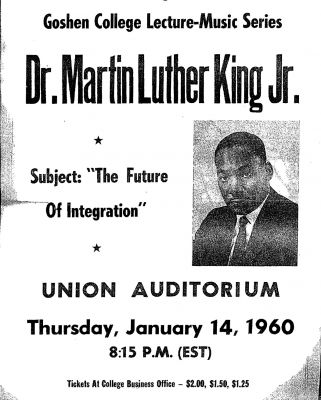

In December, King’s secretary, Maude L. Ballou, wrote and informed Smith that King’s lecture topic would be “The Future of Integration.” King also had accepted Smith’s offer to spend the night in his home and agreed to attend an evening meal before the lecture as long as it was with a “small group” from the college.

The lecture was scheduled for the Union Auditorium on Jan. 14, 1960 at 8:15 p.m. Tickets were available at the college business office for $2, $1.50 and $1.25.

Details of King’s arrival and departure later were arranged. On Jan. 7, 1960, for example, King’s secretary wrote and informed Smith that King would arrive at the South Bend airport at 4:15 p.m., via a United Airlines flight, but he no longer would be able to spend the night in Goshen. Friends would drive him to Chicago immediately after the lecture.

Weather and finances interfere

All was in place for a successful, high-profile lecture.

However, it was abruptly cancelled on Jan. 14 — the day of the lecture. The news media helped spread the word that King had been unable to fly to Chicago because of weather problems. On Jan. 15, Smith called King and the civil right leader agreed to lecture at Goshen College on March 10, 1960.

On Jan. 21, Professor Smith wrote to King to confirm the new lecture date. He also raised two sensitive issues: the need to generate renewed public interest for King’s rescheduled lecture and college “finances.”

Smith wrote that the college had spent “quite a bit” of money advertising the Jan. 14 lecture and preparing the Union Auditorium for the event. The college also had given ticket refunds to those who could not attend the rescheduled lecture on March 10. The total loss to the college: $200, according to archive correspondence.

“In view of this, I am wondering whether you would like to reconsider the $600 fee that we had agreed upon,” Smith wrote to King. “I do not mean at all that we would want you to consider bearing the entire added expense, because it was not your fault any more than it was ours that the lecture had to be cancelled.” The college still was willing to pay King $600, Smith wrote, but a lower speaking fee “would enable us to stay out of the red and we would still be able to put out adequate publicity for the rescheduled lecture.”

King’s secretary responded in a Jan. 27, 1960 letter in which she suggested lowering the speaking fee to $500. Smith accepted the new fee in a letter dated Feb. 9, 1960. And he again invited King to spend the night in his Goshen home.

Maude L. Ballou, King’s secretary, responded that King’s travel plans for March 10 were not settled but that he would lecture at the college despite some personal problems.

“As you probably know, the state of Alabama has attacked Dr. King on a charge of perjury regarding income tax,” Ballou wrote on Feb. 22. “This has caused him quite a bit of strain because this is an attack on his integrity and honesty. Of course, we feel that it’s just another attempt to harass him and embarrass him.”

The news clearly worried Professor Smith, according to archive records.

“According to press reports, I notice that the state of Alabama is trying to harass you apparently because of your stand on civil rights,” Smith wrote to King on Feb. 24. “I am assuming that this will not in any way interfere with the possibility of your being here in March 10. Is that correct? We certainly hope so.”

Ballou responded with a letter on March 5, in which she reconfirmed the lecture and provided King’s travel plans. She also noted that King’s busy schedule would force him to leave Goshen immediately after the lecture and that he could not spend the night at Smith’s home. “He wants you to know, however, that he is anxiously looking forward to being with you, the faculty, and students at Goshen,” she wrote.

And, indeed, King did speak at Goshen College on March 10.

A ‘meaningful and enjoyable’ visit

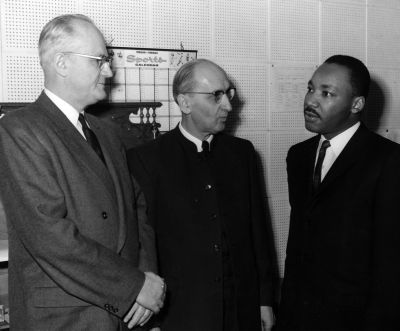

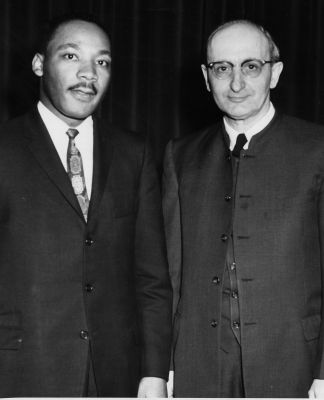

The Goshen professor also told the crowd he strongly endorsed King’s work.Professor Guy F. Hershberger, who had met King several years earlier during church conferences in the South, introduced King to the crowd. Hershberger described King as “a maker of history; a man who at the age of 27 had not only completed a distinguished academic career, but who had become a world figure as well.”

“Martin Luther King is not merely a champion of civil rights. He is also a minister of the Gospel whose roots are deep in the Christian heritage. He speaks out of the deep religious experience and the sacrificial suffering of his own people. He has repudiated all violence,” Hershberger said.

“For four years he has demonstrated a better way for the achievement of freedom; a new road to the pursuit of happiness. In this age of the hydrogen bomb and the intercontinental ballistic missile, it is our hope that this voice shall continue to speak for peace and freedom as the days go by.”

King apparently enjoyed his lecture and brief visit to Goshen College.

After returning to Atlanta, Ga., he wrote a letter to Professor Smith, on March 25, 1960, expressing his appreciation for a “meaningful and enjoyable” visit.

“The fellowship was rich indeed. My only regret was that circumstances made it necessary for me to rush in and rush out,” King wrote. “I hope the time will come when I will be able to visit the campus and spend a little more time.”

Professor Smith responded to King a few weeks. He wrote that he also regretted that King’s visit had been so brief. “If you ever come through this community, be sure to stop off and see us if you can. Our latch string is always out.”

In his letter of April 6, 1960, Smith also praised King for his “excellent” address, which he noted had been well received on campus.

“May God bless you in your further work,” Smith wrote. “Here at Goshen we are all for the work you are doing, and we hope to do our part in helping this great work to be a success and we appreciate also the methods which you use and emphasize.”

The following month — on May 28, 1960 — an all-white jury in Montgomery, Ala acquitted King of the tax evasion charge.

Eight years later — at sunset on April 4, 1968 — Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn.

Like much of the rest of the world, Goshen College mourned.