President’s Speech: The Intercultural Transformation of a Midwest Mennonite College: ¡Si Se Puede!

On Oct. 11, 2016, Goshen College President Jim Brenneman delivered the keynote address at the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities (HACU) Dean’s Forum in San Antonio, Texas.

Buenos dias a todos. I know I’m taking a big risk to start this talk with statistics, since it is statistically significant that anything associated with statistics is boring and often misleading. Or as Abraham Lincoln once said, “The problem with Internet quotes is that 55 percent of them aren’t accurate.”

Actually, the stats I am happy to share are anything but boring, in my opinion. As of this fall, Goshen’s Hispanic undergraduate enrollment is 20 percent. International and students of color make up 16 percent. In total, 43 percent of our traditional undergraduate students are from non-white groups. We expect that in just two more years we will become an official Hispanic Serving Institution! That will make Goshen College the second HSI in the state, the only one located in a non-urban area, and the only one that is a member institution of HACU. The first HSI in Indiana is outside of Chicago, Calumet College of St. Joseph (not a member). No other private or public college or university in Indiana is within reach of HSI status for the foreseeable future. In that sense, GC is unique in the Midwest!

Now to understand the joy and excitement we feel about such statistics, one has to know a little of our history. Just 10 years ago, only four percent of our students were Hispanic. A lot has happened since. So I’m here to share the story of the amazing intercultural transformation of a liberal arts Midwest Mennonite College of a thousand students and its positive impact on the economic, civic and cultural vitality of our region.

A Midwest College

To orient you geographically, Goshen College is about halfway between Chicago and Toledo and half-way between Grand Rapids and Indianapolis. In other words, we’re in cow country (and chicken and hog country, too). By last official count, humans of Elkhart County were only seven percent of the total population, if you include livestock. Welcome to the Midwest, which once was America’s economic powerhouse.

In his book Caught in the Middle: America’s Heartland in the Age of Globalization, Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Richard C. Longworth described the Midwest as the “Silicon Valley” of the industrial revolution. That, indeed, we once were and could be again. He argues that one key to our economic revitalization as a region has to be immigration — more people moving in than out — just as it was in the industrial revolution. A 2015 study of the 20 fastest growing regions in the U.S. by Indiana’s Economic Development Corporation listed the top reasons for the phenomenal economic growth of those regions as: immigration and quality of life. Both Longworth and the IEDC’s studies concluded the additional element needed today, which was not as necessary during the Industrial era, is education.

It’s the height of irony, then, that in so many rural areas throughout the Midwest, whose towns are being abandoned, whose quality of life is deteriorating, we find so many opponents of immigration reform, if not also funding for education. If only one would listen to almost any economic news report of any reputable news organization, one would quickly learn that immigrants or children of immigrants founded 40 percent of this country’s FORTUNE 500 firms and millions of smaller businesses. If only one would listen or read. Hence, the necessary power of education in this transformation.

I share this to say that one of the wonderful outcomes of Goshen’s intercultural transformation has been to effect the narrative in our region from an extreme anti-immigration stance to a growing appreciation for the economic, quality of life, and vibrant civic and cultural contributions of new immigrant families into our community. Of course, there has been backlash, but that too is becoming more episodic than lasting, especially during political seasons such as this.

The amazing shift in consciousness in our city is truly remarkable. The City of Goshen was once a ‘sundown’ town, after all, where African-Americans were not allowed to live. In the City of Goshen today, nearly 30 percent of our population is Hispanic, and Hispanics make up 52 percent of students enrolled in the Goshen Community Schools.

And today, at 15 percent of our population, our county has the third highest percentage of Hispanic residents in the State of Indiana (75 percent increase from 15 years ago) — the first being in Lake County (Chicago), the second Marion County (Indianapolis).

Suffice it to say, the intercultural transformation at Goshen College has taken place in the middle of a tumultuous civic debate in a mostly “red” state with fault lines all around that could have and at times have made town-gown relations difficult. Today, that relationship, however, is at an all-time high and is part of the power of transformation that is happening in our college and community. I will say a bit more about that later.

Mennonite College

When we speak of an intercultural transformation at Goshen College, we’re doing so from the perspective of its 122-year history. Since its beginnings in 1894 and for the next 90 years, 95 percent or more of our student body was culturally of Swiss-German Mennonite heritage of the 500-year old peace church tradition.

Student demographics began to shift a bit in the ‘80s, both in terms of the increased percentage of non-Mennonite students and also small increases in the percentages of international and intercultural students. As I said, in 2006, when I arrived, only four percent of our students were Hispanic.

What led to the intercultural transformation of Goshen College?

I’m tempted to describe in detail the many strategies that we undertook to create these changes on campus; and will list some of them in a minute. However, because it is true what Peter Drucker said some years ago that “culture eats strategy for breakfast every time,” I will focus most of my comments on how we worked at the cultural changes necessary so that the strategic initiatives we implemented would last. And a reminder here, this work had to be done while the college ship was sailing through one of the worst economic times since the great depression. Perhaps, that was a blessing in disguise. What I can say, it was not inevitable that Goshen College would make the choice to become an HSI. In fact, other possibilities for transforming GC might have proven to be more attractive, especially for some stakeholders who did not altogether appreciate the rather radical transformation of their alma mater. I have quite a few letters on file to substantiate that reluctance, even passive resistance.

Mennonite Values for Everyone

One major shift of consciousness would have to be a shift in mission from being primarily a Mennonite college for Mennonites alone, to a college of Mennonite values for everyone. To make that shift, we had to remind ourselves of our own unique heritage and what it might mean to carry it into the 21st century in new ways.

The Mennonite faith tradition grew out of the university setting in 1525 in Switzerland and Germany. About 250 years before they were enshrined in the constitutions of any Western democracies, the values of the original Anabaptist/Mennonites were defended even to the point of martyrdom. Those Mennonite values were: the separation of church and state, the inviolable right and protection of minority dissent, and the inherent worth of every individual.

Mennonite values also meant that in 1688, 200 years before the Emancipation Proclamation, Mennonites and Quakers were publicly on record that no member of their communities of faith could hold slaves. Later, many Mennonites went to prison, some even dying in Leavenworth during WWI, in order to persuade the Supreme Court to interpret the first amendment of the constitution as allowing conscientious objection to war for reasons of conscience and religion.

An appeal to this 500-year old tradition of peace and social justice, which served as the foundation of the formation of Goshen College itself and that called us to be engaged in social justice work from our founding, served as the perfect backdrop for applying those values to their latest iteration: GC undergoing an intercultural transformation.

GC’s first president had long ago articulated GC’s motto “Culture for Service,” which would become a deeply held value integrated into the fabric of the institution from its beginnings.

In 1968, as a regular part of our reaccreditation process, it was noted by the reaccreditation visiting team that some 60-70 percent of our faculty had studied, lived, taught, worked, were born, and/or did service abroad. It was then that Goshen College started its now famously unique Study-Service-Term that is still a graduation requirement of every student. Cohorts of students and faculty would travel to now over 24 developing countries all over the world for a semester, after having learned the language, to live with families, study culture and language, and then serve in Peace Corps-like settings linked to their majors or minors. Goshen is now recognized as having the fourth best international studies program among U.S. colleges and universities. So once again, GC had already committed itself to cross-cultural education as part of its core identity as a university — a harbinger of the intercultural transformation that would emerge in 2006.

If the intercultural experience was mainly one that exported students and faculty from campus to countries abroad, what would happen when the “world community” began to move next door en masse as it would in the early 2000s and beyond? Everything that had made us who we were as an institution, our unique Christian heritage, our values of peace and justice, our intercultural experiences abroad — all now compelled us to re-examine our commitments to these first generation, new immigrant populations right in our midst.

Our dilemma as a college was simple: the actual facts on the ground with regard to our diversity on campus fell far short of our historic claims of wanting to be a more diverse campus. If accrediting bodies truly held us accountable for what we said about wanting to be a more culturally diverse campus and our actual outcomes with regard to those claims (like they do on learning outcomes), our accreditation would have long ago been revoked. Minimally, our reputation was at stake.

The Positive Perfect Storm

Fortunately, a “perfect storm” of a wonderful kind happened at Goshen College, which, because of GC’s already historic core values and international commitments, launched us into making our dreams into reality. In a real sense, this is the story of how “luck favors the prepared.”

We were very fortunate that right at this time, the Lilly Endowment, Inc. had begun inviting colleges and universities to consider initiatives that would be transformational for their institutions. Again, GC could have asked for money to start a pharmacy school, or some other new program. We did not do so. Something in our spiritual bones compelled us to consider a different kind of transformation. Soon after my arrival in 2006, Goshen College received a $12.5 million grant to establish the Center for Intercultural Teaching and Learning (now the Center for Intercultural and International Education), which would help propel us forward into the new path we had set for ourselves.

For the first time ever, we wrote a forward thinking vision statement that moved us from that of a mostly “family”-centric institution (where who you know matters, where policies favored “the family” over others, where belonging mostly happened for those already a part of the Mennonite family) to a vision-driven institution. There would be no turning back.

Together, we created a vision statement that read: “Goshen College is an influential leader in liberal arts education focusing on international, intercultural, interdisciplinary and integrative teaching and learning that offers every student a life-orienting story embedded in Christ-centered core values: global citizenship, compassionate peacemaking, servant leadership, and passionate learning.”

From that day to this, we have used that vision statement to drive every decision we have made and continue to make from the boardroom to the classroom. Hundreds of decisions were made, all answering to that vision statement in some deliberate way. Some changes include:

- A campus wide cultural audit was made; every recommendation implemented

- One third of our Board of Directors are now people of color

- We changed the faculty hiring policy that was weighted 80/20 toward Mennonite faculty leaving little room for hiring diverse candidates.

- We revamped our recruitment plans to focus more regionally, changed financial aid categories, names of scholarships; recruited families (not just student alone), classes for families on higher education, etc.

- Summer SALT immersion program on campus for first time college students to get adjusted.

- Spanish materials, website options in Spanish, began education-focused show on higher education in Spanish on the local Spanish radio stations.

- Spanish speakers at all front-line service areas

- Bilingual Academic Learning Center for coaching, writing, etc.

- Redid our core curriculum to ensure intercultural learning, reflection, experience; the ICC: Identity, Culture and Community first-year required class provides great orientation; prepares students to go on Study-Service-Term out of country.

- Art on campus is reflective of our intercultural make up, as is naming of some buildings

- Capital campaign builds a case-statement around our vision.

- New hires, or programs — funds allocated or reallocated to those that fulfill vision statement.

- Flipped-classrooms help first generation succeed; teachers graded (as much as students) for their intercultural capacity to teach diverse groups.

- Human Resources: we have a nine-point hiring policy that affirmatively seeks out faculty, administrators and staff of color; including additional dollars for hiring or to provide educational training needed to move up through ranks to higher levels; also implemented sweeping intercultural competency training and seminars as part of annual review of each employee.

- Our student employment track revised; now Student Senate, Resident Assistants, ministry leaders; all include intercultural leaders; 4 year leadership track for all Intercultural scholarship recipients.

- Our World Music choirs; El Sistema link to Longy School of Music for Social Change

Strategic initiatives like these were all important in transforming the campus culture, but so was having the right leadership in place at the right time.

Leading the GC transformation

I am grateful for Presidents Council members, the provost and deans and department chairs and all those who have fully embraced GC’s intercultural vision. I am grateful for leaders in the physical plant, the sports programs, in the student senate and throughout campus who have been inspired to help make this vision a reality. I am thankful for the leadership of Richard Aguirre, director of corporate and foundation relations; and Rocio Diaz, CIIE coordinator of intercultural community engagement; (who are with us today) and Gilberto Perez, Jr., senior director of intercultural development and educational partnerships/co-director of CIIE, without whom this transformation story could not have happened in many of the profound ways that it has. [And also Dr. Rebecca Hernandez, our first director of CIIE].

If you allow, I will indulge you with a story from my own experience to underscore the honor and privilege it has been to help lead this transformation at GC. I acknowledge, at least in hindsight, that something wonderfully serendipitous, maybe even divine, brought together pieces of my life in ways unknown to me to prepare me to lead this transformation.

Legal decisions about educational access coupled with my own life experience as a child growing up in the “apartheid” south, alongside my spiritual formation in a peace and justice-oriented family, helped prepare me to return to my alma mater as its sixteenth president in 2006. Part of the perfect positive storm.

I grew up in the Cuban quarter of Ybor City in Tampa, Florida. My school and church were integrated and bilingual. However, many other public spaces were still operating under the “separate but equal” ruling of the Supreme Court (1896) in Plessy vs. Ferguson. In the year I was born, Plessy was overturned by the Supreme Court in Brown vs. Board of Education (1954), which compelled schools to integrate kicking and screaming, some through active and much passive resistance.

By way of GC context, seven years before Brown vs. Board of Education, in 1947, the first African American student, Juanita Lark, graduated from Goshen College. Our Welcome Center was recently named after her.

The first four Latino students were welcomed around that time as well. One of those students, Octavio Romero, lives here in San Antonio with his wife Pita. Their generous philanthropy has provided six different named scholarships at GC. And now, our largest student housing building has been named the Octavio Romero Student Apartments. Such naming, plus art from around the world displayed throughout campus at strategic locations, provides a sense of belonging for all students, especially those of color.

Meanwhile, back home in Tampa in the early 1960’s, my father challenged the racial segregation of the status quo by taking our family to the “colored” side of the beach. He would remind us that Tampa Bay and its beaches belonged to God and no one else. He would also refuse to drink from water fountains, like the one at the corner gas station from our house, that had a “whites only” sign above it.

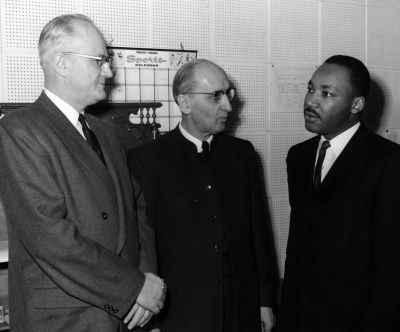

About that time in 1961, Goshen College had welcomed Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to speak on campus to a mixed welcome in the surrounding community. A few years later, GC started its SST program in the same year the Voting Rights Act was passed (1968). It was that same year that Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, the Vietnam War was underway. It was a very tumultuous time for a fourteen year old trying to sort out life, school, and church, be it in the community and at home.

I should note here that my mother had an eighth grade education, having grown up Amish in Iowa. My father would eventually get his GED during my childhood. Mom worked as a seamstress at home with a sign for business on a post out by the street. Dad worked odd jobs, at night as a janitor or gas station attendant and during the day other jobs as well. Dad or Mom didn’t know anything really about applying for colleges, much less financial aid papers, and, for sure knew they couldn’t afford helping me go to college. I was on my own.

And so, I dropped out of high school, in part, because I was lost in a sea of busing, a strange new school, not knowing anyone, navigating through a racially charged school system. I eventually did get my diploma at night school and on a fluke applied to Goshen College. I got accepted and came to Goshen College sight unseen in 1973.

The Goshen College I entered was still 95 percent Swiss-German Mennonite students from all over the United States. It was the most segregated school I had ever been to by then, even though its values and commitments were generously inclusive and socially conscious. And the rest, as they say, is history.

I did learn first hand by being a first generation city kid at Goshen College — that Goshen could prepare a bright kid like me, with a little financial backing, a few loans, to go on to do two masters degrees and a Ph.D., become a seminary professor, a published author, an ordained minister and even a college President. That GC experience coupled with my childhood experiences in Ybor City, my SST service in Honduras and living another 26 years in Los Angeles area, created a driving passion in me to help implement the transformation that would become the Goshen College I am describing for you today.

Affirmative Action Addresses Systemic Bias

Of course, inertia, implicit bias, unexplained oral-tradition, sacred cows, Mennonite-privilege, all had a way of working against the very ideals we truly supported on campus. Some of the resistance was not personal per se, but was the result of systemic forces that folded in on themselves to keep the status quo alive. In other instances, even when we tried to do the right thing in the right way, change would still not happen. I was reminded of how systems themselves take on lives of their own that make this work so difficult.

Still, if the Supreme Court decision in Fordice vs. U.S. (1992), taught us anything, it taught us even though we had passed laws overturning segregation thirty years earlier, that in spite of our best intentions, affirmative action would be necessary to help right the ongoing discriminatory effects of systemic discrimination. If that’s true legally, then it is even more so morally. In similar ways, systemic resistance on campus could override even our best intentions. Knowing this, I was strengthened in my resolve to encourage the use of affirmative action steps to help right the moral educational ship of Goshen College on its intercultural destiny.

I have, indeed, been sensitive to questions of “fairness” (usually not malicious in intent) by those in the majority, especially given higher education’s proclivities toward fairness across the board. Equity and excellence are so often pitted against each other. And so, I have tried to stand firm when the value of perceived equality and fairness, in fact, undermines the goal of true equity in educational access, educational support services, faculty remuneration, allocation of financial aid resources, that support the intercultural vision we have agreed to be our north star. Having a common vision helps us to push forward together. In a Christian context, we are able to always come back to the fundamentals: WWJD? What would Jesus do? Give a cup of cold water to the thirsty, clothes to the naked, freedom to the captive; and why not then, the ABCs or a good education to the first generation kid in poverty who needs it to escape his situation imposed upon him by his birth. WWJD?

I was advised early on by an older and wiser GC president that whatever changes we made at Goshen College, they had to be vision-driven, deeply systemic and infused into the very fabric of the institution itself. We have worked methodically and diligently at all levels of the institution to do just that. I have sought to make changes such that any future regime would have to work just as hard or harder to turn back the intercultural tide which has become Goshen College.

I speak of this stubborn affirmative commitment to our vision, even when it’s not always popular, knowing that our faculty, administration, and staff have truly embraced the vision of who we are becoming. I am a keeper of the vision, first and foremost.

Recently, a faculty member wrote me a note expressing his gratitude for the work we’ve been doing. “Almost semester by semester, I see my classes getting more diverse,” he wrote. “This fall I will see what I could never have imagined, one of my classes has NO (zero) Caucasian students! That’s no kind of goal in itself, of course, but it’s an indicator of where we have arrived. What’s your phrase? ‘A Mennonite College for the Whole World?’ That’s a mission I’m excited about working at for the rest of my teaching career! Thank you for leading us there.” I don’t get those notes everyday. But am grateful when they come.

Transforming Town-Gown Relationships

As I began this talk, I noted that one of the other truly remarkable outcomes of this historic transformation has been the transformation of our community as well. Our transformative experience has attracted interest in what’s going on at the college. We have placed ourselves on every civic and governing and economic board we can in order to sing the praises of intercultural transformation. And to our delight, it is taking hold. This was not the case 10 years ago, when even the word diversity or intercultural or immigrant would bring derision, eye rolling, and skeptical comment. The town-gown transformation has been particularly gratifying for all of us.

One story worth telling is how intercultural transformation is becoming contagious. The local high school began offering the prestigious International Baccalaureate diploma (GC gives a full year of credits for this). Whereas being bilingual in the past had been viewed as a liability, the IB program turns it into an asset. At the last high school commencement slightly over half of the full IB students were Latino. The tide is turning on misguided perceptions of Latinos in the local schools that, in the past, stimulated “white flight” to even more rural school districts. Our local schools are getting prestigious rankings by U.S. News and World Reports, in part, because of their commitment to intercultural transformation. The Hispanic students are graduating at the top of their classes. GC has to compete at times for Hispanic students accepted at Harvard or MIT, sometimes he/she chooses GC because they experience a sense of belonging here and are closer to family for commuting purposes, as well.

Our local chamber of commerce has invited GC representatives on its board and to be a resource to area businesses for intercultural competency training. We have partnered with the Chamber to offer Young Business Leadership Academies with an intercultural focus. Millennials are staying in Goshen and others are returning, in part, because of the quality of life offered, including its intercultural vibe. Turns out, the vast majority of millennials prefer not to live in monocultural communities. Folks in Goshen are taking notice.

With growing cohorts of Hispanic grads, who are now working in regional banks, in hospitals, in labs and corporate firms and nonprofit agencies, we have entered a new phase of support: encouraging and coaching them in how to join boards, run for office, become the future leaders in our region, fully integrating into the life of the community. They are the future.

The newly elected mayor of Goshen has established a new Latino Advisory Committee made up many GC alums, current faculty, administrators, and one of GC’s Dream recipient students. We are working with the police to help with intercultural competency training; meeting with groups of Latino families who are fearful of police profiling and other concerns. Our Latino teaching graduates are practically guaranteed work in one of our Elkhart County eight school districts. Together, we are Goshen! Town and college!

These are just some of the countless ways that Goshen College has begun to be transformed and to be part of the larger transformation of our region. Such transformation is a truly reciprocal in nature, where all parties in the experience benefit and are a mutual blessing to each other.

If such a transformation can happen in the land of Goshen, both in the college and in the community, then it can happen anywhere where people are willing to learn from each other, to listen to one another, to help each other make dreams of becoming a beloved community, a world house of learning, a reality. So as Cesar Chavez, and later Barack Obama, proclaimed, “Si, se puede. Yes, we can.”