|

Observation

Drawing

|

The Objectives:

-

Practice observation drawing because children who gain drawing

confidence through observation practice will less likely have the crisis

of confidence. A crisis of confidence about drawing tends to

extend to other aspects of art and is very common among children and adults

in our society.

-

Encourage creative work habits.

-

Change habits of work by selecting things that can not easily

drawn from memory.

-

Learn about significant art history, art criticism, and aesthetics.

NOTE: To assure

observation, do not show any examples or any artwork from art history

until near the end of the lesson after the students have completed their

own work.

Age and Grade

Level

This is a good lesson for grades three to adult. This lesson

is best above second grade, but younger children do well with it if the

blinder is not used. Younger children do well if they are encouraged to

study each shape carefully before drawing it. I find that it is okay

to encourage them to make lots of mistakes and draw over the mistakes so

they can learn more. I tell them that I always make mistakes when

I am learning a new thing. That is how I learn it. I tell them

that when they are finished, they may erase the parts that are not as good,

but leave the lines they like best. These instructions help them

overcome the fear of failure.

Media

-

Distribute the materials before discussing

the process and giving drawing directions. This is avoids disrupting

them when they are ready to start working.

-

Use any drawing media that students are already

familiar with. Select paper that is large enough for the drawing

tools and art media being used. For charcoal, pastels, oil pastels

and paints you could use 12 x 18 or larger. If they work with drawing

pencils, ink, ball point, or with small brushes, use a smaller size if time is limited. This might depend on the the age and prior experience

of the students.

Review and Introduce

The teacher briefly reviews previous lessons

that have been similar or related to this lesson. The teacher gives

a brief introduction and explains what is going ot happen and explains

a few things that will be practiced and learned in this lesson.

In this lesson the rabbit was kept secret and hidden until it was used.

This avoided distraction before they were ready to draw it.

Preliminary Warm-up

-

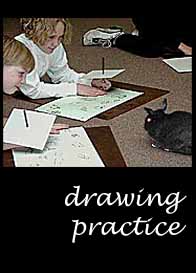

Students place their 6B soft lead drawing

pencils through a hole in the middle of 8 x 8 inch card which serves as

a blinder preventing the temptation to look at their paper.

-

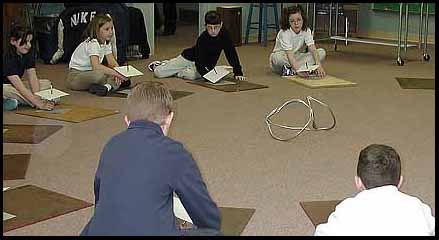

The class does some warm-up practice blind

contour drawings of something they have never

seen before. Here a piece of soft aluminum cable is used

because it can easily be bent into new shapes. It is easy to follow

because it is linear.

|

By using an unfamiliar subject, the teacher

can be confident that students will not draw from memory, but they will

actually want to observe the lines and shapes they see.

|

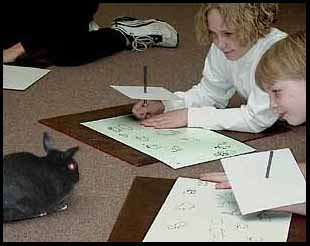

- Here a pet rabbit is allowed to roam the room.

The rabbit becomes the subject of more practice blind contour drawings.

-

Students are asked to continue their lines

when the rabbit moves, allowing unconventional renderings. This gives

them "permission" to make "individual" renditions.

-

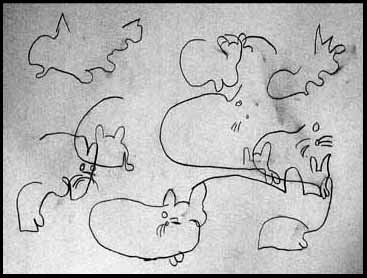

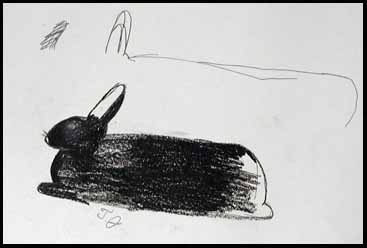

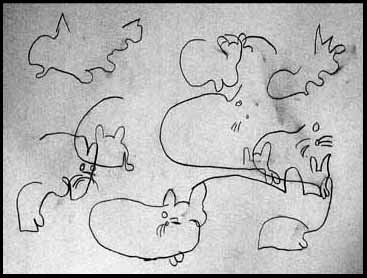

Below is a sheet of these practice observations.

|

|

|

A

live animal is very engaging and creates very strong attention and motivation.

We are naturally drawn to animals. They are probably one of the best

subjects to use for an art assignment.

Teachers need

to check to be sure no children in the class have an allergy to a particular

animal and they need to make sure school policies do not prohibit animals.

|

Final Project

-

Students use a new sheet of drawing paper.

-

They are asked to make a larger drawing and

attempt of fill the paper.

-

They are allowed to try several times until

they get an outline they like.

-

Using crayons, they are encouraged to add

the texture and tone (values) they observe.

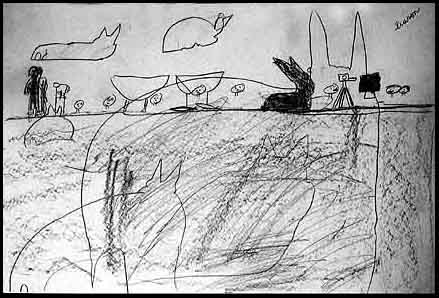

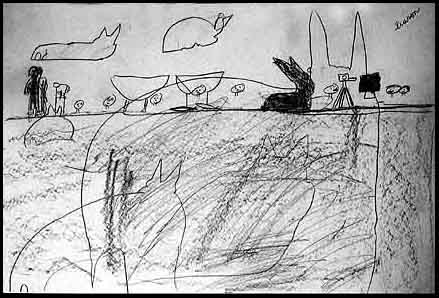

The drawing

below by a third grade student is unique in that the student drew the whole

scene including the children on the floor, the teacher standing on the

left and the camera on a tripod at the right. |

This drawing by a third grade student

shows that the student felt free to start three times, each time making

an observational improvement.

|

|

Displaying

Work

Be inclusive and educational.

-

Include every child's

work each time or at least use a fair rotating basis.

-

Public displays need

to include the teacher's goals and objectives

to help educate other children, teachers, parents, administrators, cleaning

staff, and others who may wonder what is being learned.

-

Teach children how to

put up these orderly well designed displays by themselves.

|

Discussing Student Work (the

dreaded critique)

-

The teacher's main

roles are to ask questions and

reinforce

articulate comments from students. Some

teachers find this difficult because it is so easy to see mistakes in student

work and talk about them. When we make suggestions or when we say

what is 'wrong' with the work, we are implying that art is supposed to

look a certain way. Too often this is simply the teacher's way.

-

Students must be allowed ownership.

Students do not make perfect work, but they make real work that reflects

their own efforts. There is a lot to learn from student efforts without

being negative.

-

In a negative and judgmental environment they

tend to do as little as they feel they can get by with. They ask,

"Is this good enough?"

-

They should ask, "What else does it need?"

At this point the teacher does not make a suggestion, but turns the question

back to the student, "What are some things you can think of?" "What

part is working best for you so far?" "Good. How could you make the

rest work that well?"

-

Try questions like:

"What do you notice first when you look at this one by . . . . "

"Why do we notice that?" "Did somebody notice something different?"

"Can somebody explain the reason for that?" "Which is one of most

original approaches you see?" " What is different about it?"

Do not allow negative remarks. When a positive remark is made, ask

for elaboration. Be sure reasons are articulated. Use a lot

of encouraging comments like, "Very good, thank you for explaining that."

-

It can be good to speculate about the meaning

of their pictures (interpretation). Making up titles helps with this.

After others have given their ideas, give the creator a chance to give

an answer.

-

We can ask about the

art

elements and compositional principles in the work. "Can somebody

find an example where somebody used contrasting size to make something

more important in the picture?" "Is there an example where somebody

used several different textures to make a picture look more interesting?"

-

Sometimes, use written

questions, but also ask the students to write open questions that

can be answered several ways.

-

Ask the students, "What

are your ideas for other kinds of art projects you could do now to learn

more about what you just learned?" "What could you do now to practice

so you get even better at what you just did?" Art is a life-long

thought process and practice. We never arrive, we are on journey.

We are in a search.

-

If discussions are too

long, try working with small groups as they finish their work. Or,

try a rotation system where you only discuss one third of the works each

time, but all students get equal turns.

|

Art History

-

After completing their

own work, students will be interested in seeing how other artists have

approached similar subjects.

-

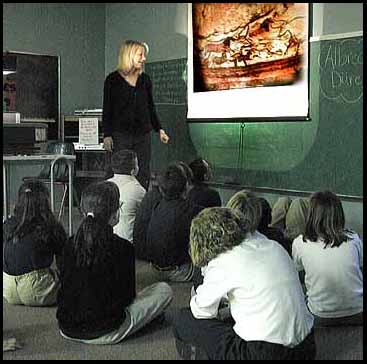

After drawing rabbits,

they will notice more about Albrecht

Durer's rendering of a Young

Hare.

-

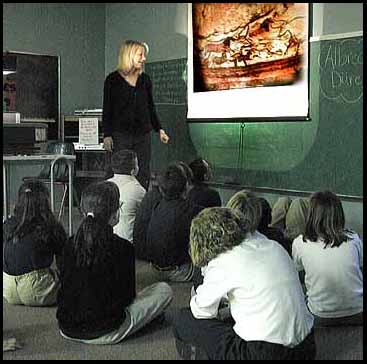

On the left the class

is discussing prehistoric animal drawings that were discovered in caves

in France.

-

In addition to "What

do you notice" and "why" questions, students can be asked to speculate

about reasons these animal drawings were created.

-

After exhausting the

student ideas, a teacher could also add what "some people think" about

the reasons.

NOTE

on IMAGE SOURCES

|

Art in Everyday

Life and Review Again

Review is very efficient use of class

time. Sometimes there is a minute or two after cleanup time before

the bell rings. Even if the bell rings before a question is answered,

it is still good to raise the question.

-

"In what country would you find very old animal

drawings in caves?"

-

"How are cave drawings and graffiti we see

on train cars similar and different"

-

"If the animal drawings in the caves were

about hunting for food, what could we draw to put on our walls in our cafeteria

about how we get our food?"

-

"How does a contour line feeling change as

you change the speed of your hand motion when you draw?"

-

"What skills other than drawing are useful

for artists?"

-

"Can you describe an example of when expressionism

is more artistic than realism?"

Review is even more effective if it is repeated

at the beginning of the next session a day or more later. When a

teacher expect students to remember things from session to session, students

thinking habits can be encouraged to remember.

Credits:

This lesson was inspired by a similar lesson developed and taught by Goshen

College art students, Patty Brown, Marlea Hershberger, Crystal Kempher,

and Tiffany Wyse. We appreciate the cooperation of teachers, administration

and especially the students of St. John's Catholic School, Goshen, IN,

for their cooperation.

|

Practice

Works. Those that do not

draw, do not learn to see very carefully. Those who do not know how

to observe, are bad at drawing. They stop drawing because they find

it discouraging. When they stop drawing they never learn it.

Viktor Lowenfeld,

the famous art educator who wrote, Creative and Mental Growth, said

some children were haptic instead of visual. He encouraged them to

be expressive instead of realistic in their artwork. Competent visual observation

did not seem to matter to him as long as children were being expressive

and creative.

In my experience

the children themselves never believe that observation drawing skill does

not matter. Why should they?

It would be like

saying those who have not naturally learned to read and write on their

own are just wired differently, so we should just teach them to talk and

sing instead. Forget writing and reading. When we neglect to

teach observation drawing, I believe we neglect basic brain development.

I am experimenting

with children as young as four. I know a child who is five and has

learned to use a blinder to practice observation blind contour drawing

before she attempts to make her actual drawing. Her blind drawings

are just for practice, but it is amazing how much she sees and includes

in her "real" drawings. When you are five, this is not strange or

unusual. It is just like learning to read, if you are instructed

this way, it seems very natural. Amazingly, it works.

Of course not every

drawing should be from observation. Memory and imagination also need

lots of practice. Young children need encouragement. I make

a practice to never correct them. I never draw for them to show them how

I draw things. Such "help" only makes them doubt their own ability

and they stop working. |

© This lesson was written by Marvin

Bartel, all rights reserved. You are invited to link this page to

your page. For permission to reproduce or copy photos, text, or layout,

or to place this page on your site or to make printed copies, e-mail: marvinpb@goshen.edu

Goshen College students are permitted to make a copy for their own use.

Marvin Bartel, Ed.D., Professor of Art

Goshen College, 1700 South Main St., Goshen IN 46526

fax: 219-535-7660

updated: December, 2001

NOTE on IMAGE

SOURCES

One way to

show copyrighted Internet images to a class is to use a computer projector

or large computer monitor and show the actual web page to the students.

This would not be making a copy and would probably be legal for educational

use (but not for business use). If this is not feasible, it is possible

to make a printed transparency of an image for limited classroom use for

a spontaneous need. In any case, the publisher should be credited so the

source is projected with the image. If an image is used on a regular and/or

repeated basis, the teacher should ask the school to get written permission

and/or purchase authorization, or purchase a reproduction or slide. The

last thing a teacher wants is for the school to become the plaintive in

a copyright case. Printed reproductions offer an advantage over slides

in that they can be displayed for a time in the classroom. Some art teachers

make a practice of checking out several beautiful art books from the public

library for their their students to enjoy when they finish their work.

This is free and legal.

Technically,

it is quite easy to take images from most web sites. Using a web

browser, one simply holds down the right mouse button

on an image to save it as a .jpg. On a Mac operating system, one

simply holds the main mouse button until the dialog box appears.

Of course lots of things are possible that are not legal.

If anybody

who is more experienced with copyright law reads this, please e-mail me

and I will try to correct any errors.

CLICK

HERE

For more about

how to "copy" an Internet image for teaching

marvinpb@goshen.edu

This is an online book of eight

drawing lessons

|

|