Andes — Part 2: The Trees

Where are they? The mountains are stunning, but something seems missing. The only forests we see are swaths of eucalyptus planted on the hillsides near each village and town. Though quite useful for firewood or supporting the roofs of adobe houses, these invasive plants imported over a century ago from Australia tend to monopolize the area they inhabit, crowding out other plants and drawing down the water table in this already-arid landscape. Have the hills always been so bare?

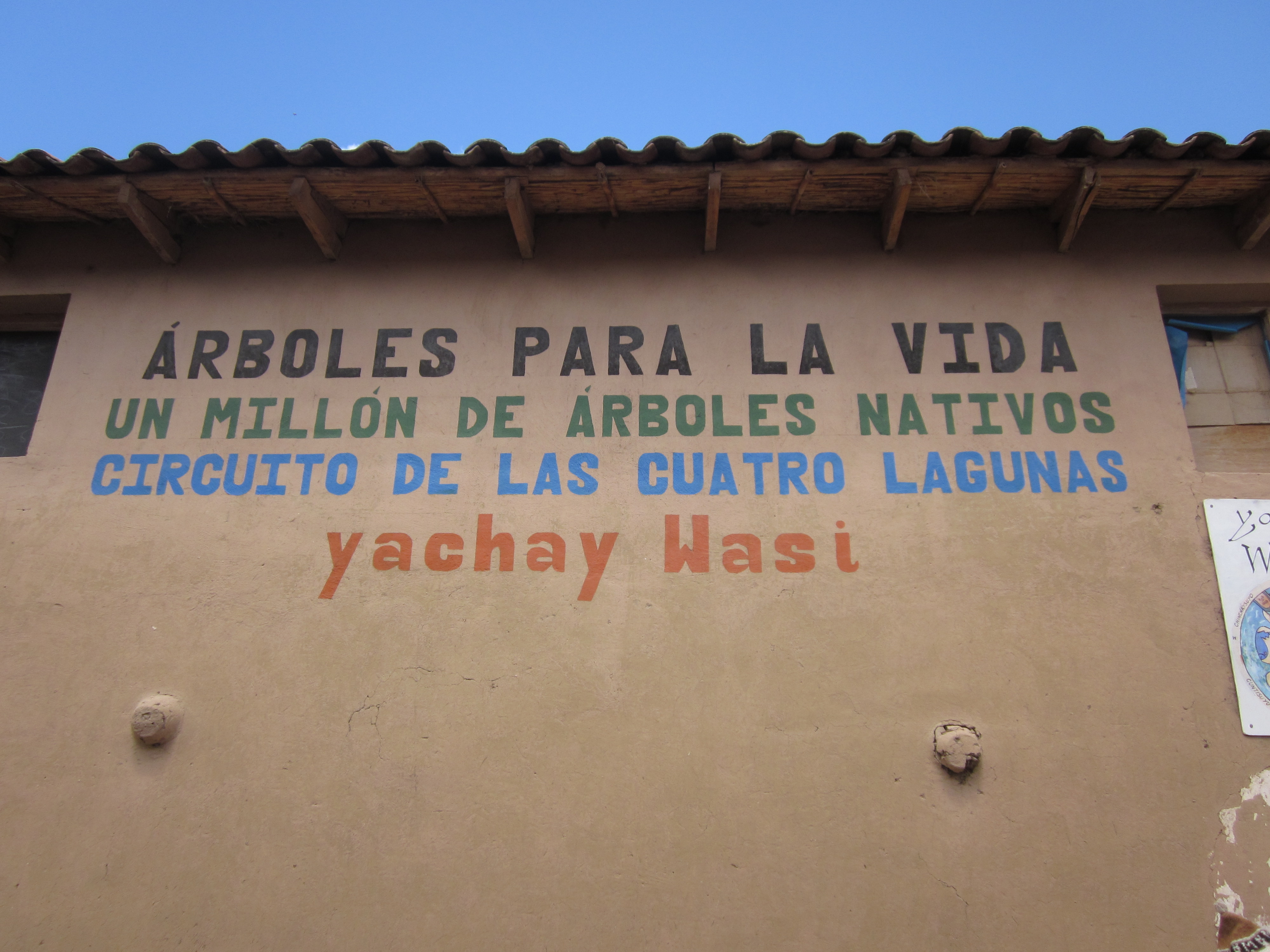

We visited the distant village of Acopia to learn more about the natural history of the Andes. Luis Delgado grew up here, moved to the United States to further his education, then returned to his birthplace several years ago to start a nonprofit organization called Yachay Wasi (House of Learning). His grandmother’s former home provides the headquarters and the surrounding mountains are his living laboratory.

Mr. Delgado and his colleague, Percy, explained how the Andes were covered in thick forests when humans first arrived in South America over ten thousand years ago. Despite the high elevation — Acopia lies 3,600 meters, or 11,811 feet, above sea level — the daytime temperature never drops below freezing due to its proximity to the equator. These relatively hospitable conditions made this part of the Andes a favorable place for human settlement and the population soon began to grow. According to pollen counts from the sediment of nearby lakes, the native forests began to disappear about 4,000 years ago as trees were felled to provide building material and firewood. Centuries of deforestation have left the mountains bare of the Queuña (polylepis incana, a member of the rose family) and other species that once reached heights of 40-60 feet.

It is one thing to learn about a problem. It is another to do something about it. So we picked up picks, shovels and the local favorite — foot plows — and set out to plant 100 Queuña seedlings just outside the village. This meant digging 100 holes, each about a half-meter (19 inches) deep. Fortunately, we had good teachers, appropriate tools, capable bodies and a great attitude, and the 100th seedling was placed in the ground a few minutes before an afternoon storm arrived to water the young plants.